David Kelly obituary in “The Guardian” in 2012

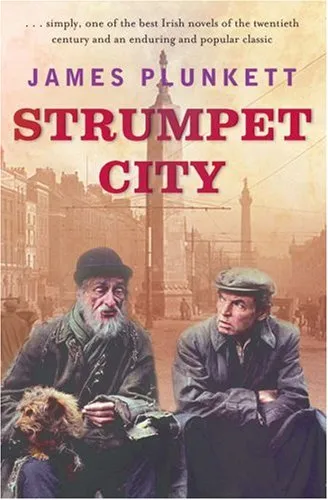

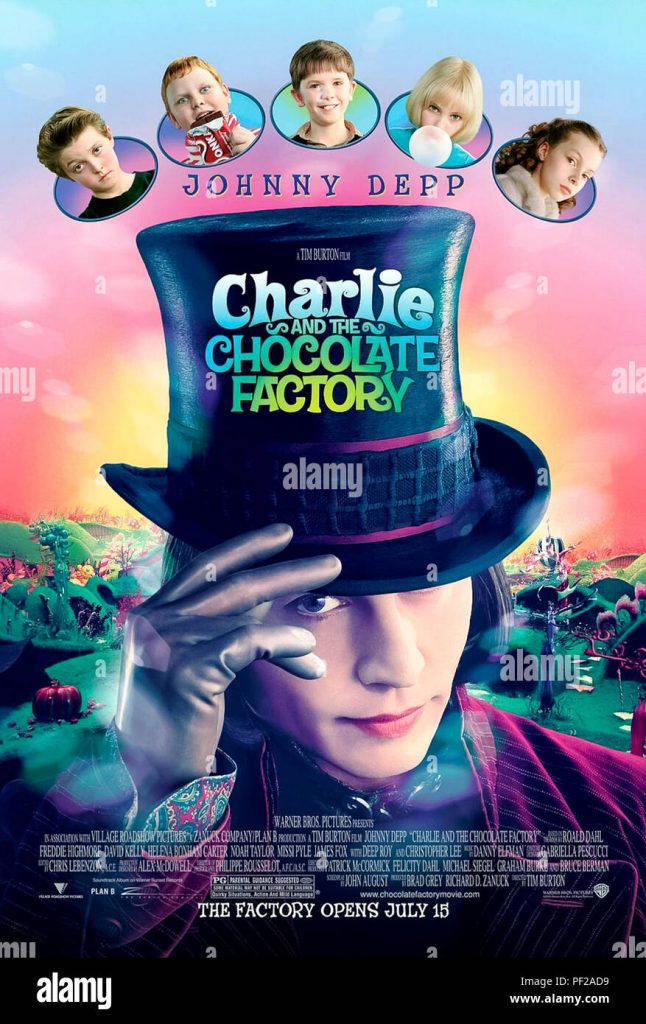

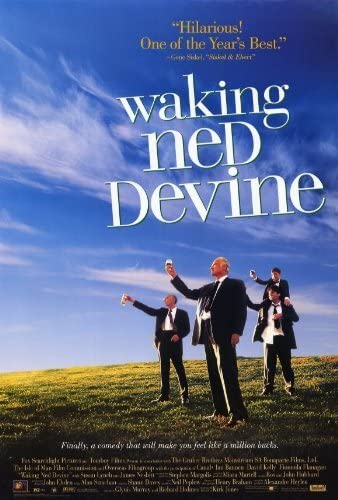

David Kelly had a long theatrical career before he starred in some early RTE television series. In 1980 he scored a personal triumph with his moving portryal of Rashers Tierney in the series “Strumpet City” based on the novel by James Plunkett. He starred as the one-armed dish washer in “Robin’s Nest” and of course was O’Reilly the Irish builde in the wonderful “Fawlty Towers”. His prominence on film came late in his career with “Waking Ned Devine” and “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory”. David Kelly died in Feb 2012 at the age of 82.

“Guardian” obituary:

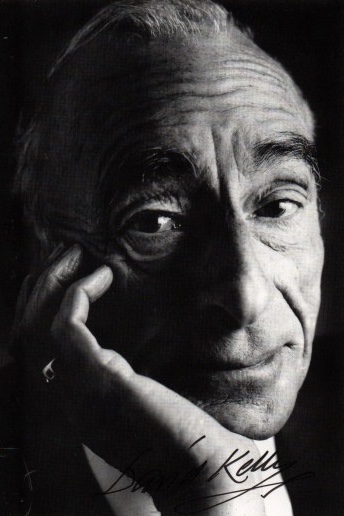

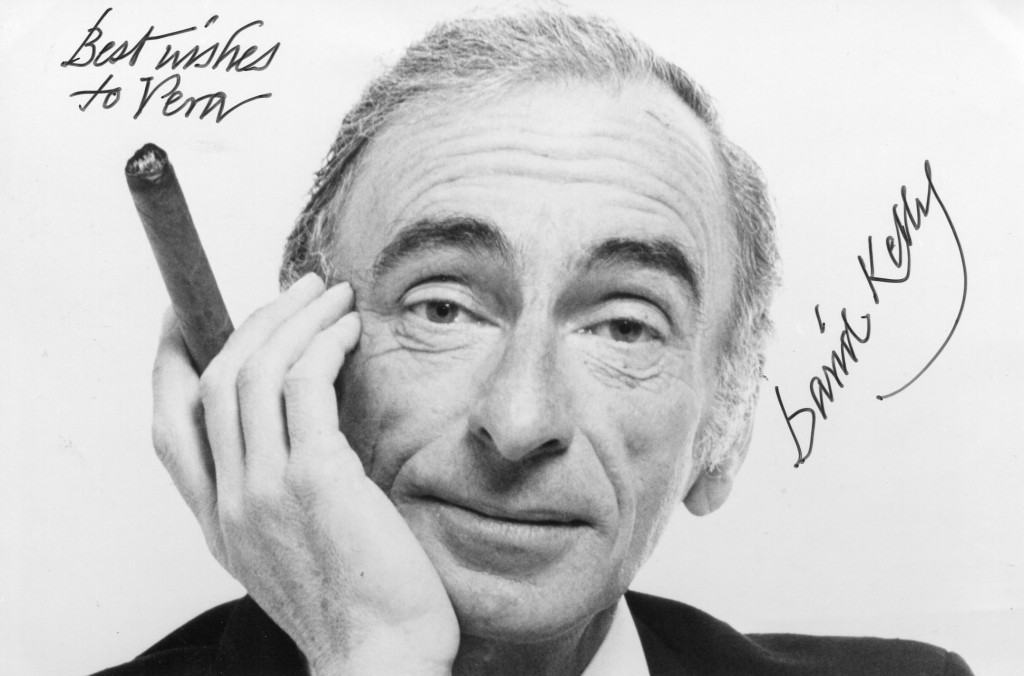

The distinctive and beguiling Irish actor David Kelly, who has died aged 82, was as familiar a face in British television sitcoms as he was on the stage in Dublin, where he was particularly associated with the Gate theatre. But he was perhaps best known in recent years for playing Grandpa Joe in Tim Burton’s movie adaptation of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), an engaging performance that was honoured with a lifetime achievement award from the Irish Film and Television Academy; Johnny Depp, who played Willy Wonka, paid a touching tribute on a video link from Hollywood to Dublin.

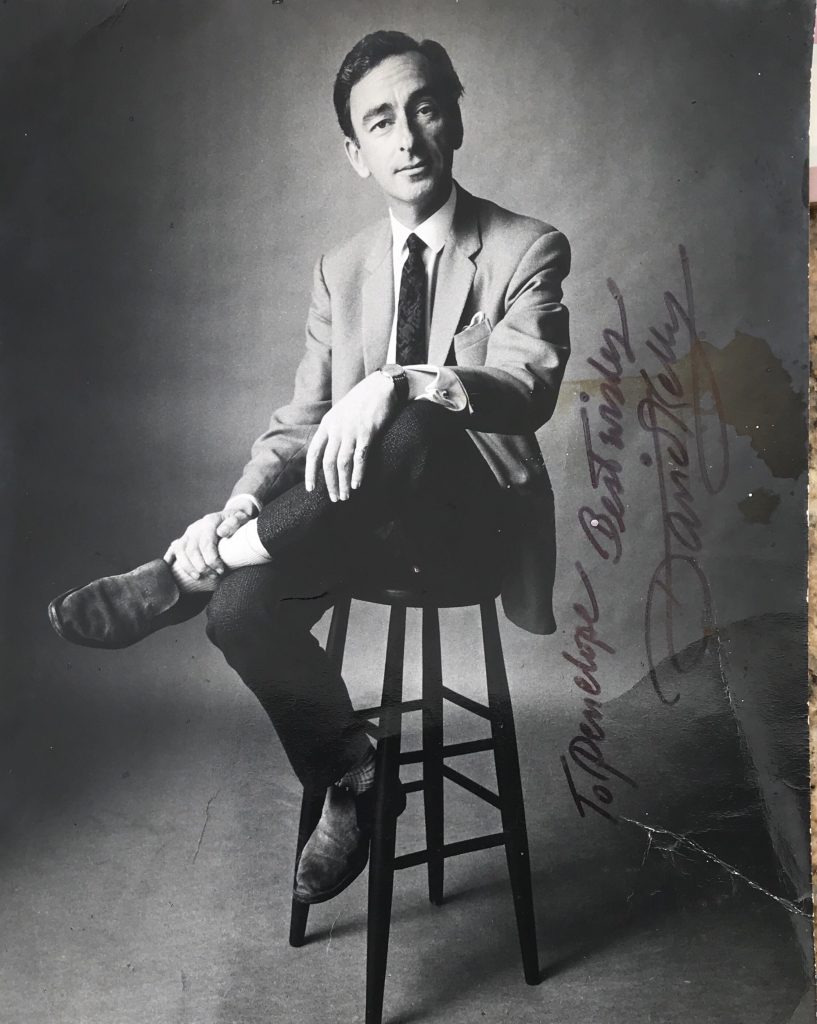

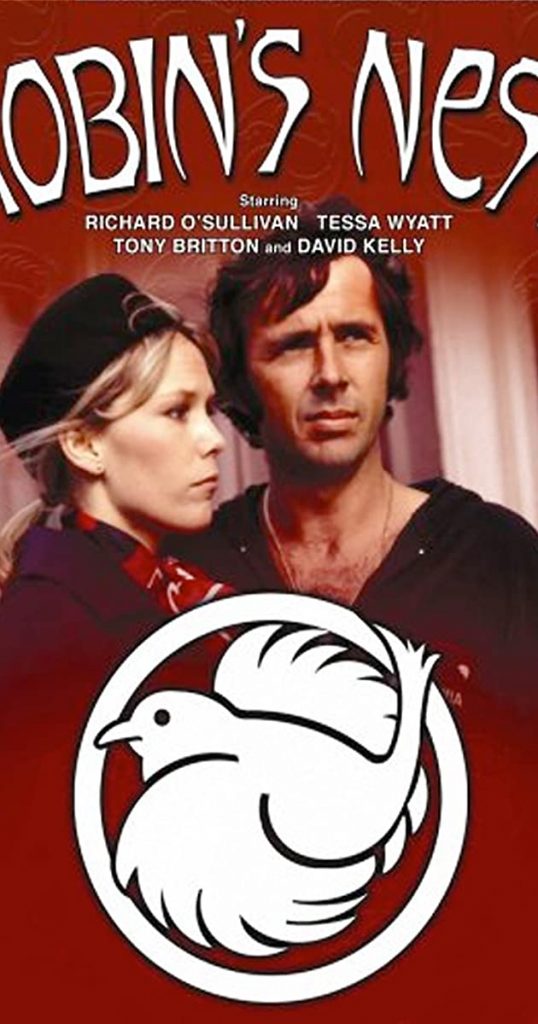

Kelly was a tall and flamboyant figure who was often cast as a comic, eccentric Irishman, notably as Albert Riddle, an incompetent, one-armed dish-washer in the late 1970s British sitcom Robin’s Nest; he could always play up to stereotype, and beyond, in his extravagant facial and physical gestures. Despite playing old codgers, he was one of life’s great dandies. His actor friend Niall Buggy said: “He was the best-dressed actor I’ve ever known – even when I look at myself.” Happily married to the actor Laurie Morton, whom he met at the Gate theatre in the days of Hilton Edwards and Micheál Mac Liammóir (they founded the theatre in 1928), Kelly was always attired off stage in hand-stitched shirts, Jermyn Street suits and a trademark bow tie.

His career spanned over 50 years, and he never considered retirement. Equally, he would never accept a role unless he felt he could add something unique and personal to it. “He was the gentleman of our profession,” said Michael Colgan, the Gate theatre director. But there were also wilderness years dedicated to drink. He told Colgan that he had no idea that President John F Kennedy had been assassinated until about 1974.

A Dubliner, he was educated at the Synge Street Catholic boys’ school and acted from the age of eight at the Gaiety theatre. His stage work included plays by Chekhov and Brian Friel; he made a rare excursion to the Abbey theatre in Friel’s Give Me Your Answer, Do! (1997), a wonderful play about the evaluation of writers and the personal crisis of a creative artist. But he was most celebrated at the Gate, where he returned in the 1990s to play Orgon in Molière’s Tartuffe, Peter in Thomas Kilroy’s version of Chekhov’s The Seagull and, most famously, Al Lewis opposite his close friend Milo O’Shea in Neil Simon’s The Sunshine Boys in 1996. That last production is still spoken of with awe in Dublin theatre circles, but he dug even deeper in a great performance of Beckett’s solo memory play, Krapp’s Last Tape – which he had first played at its Irish premiere in 1959 – and made this revival a cornerstone of the Gate’s Beckett festival in 1991; it was later seen in New York, Chicago and Melbourne.

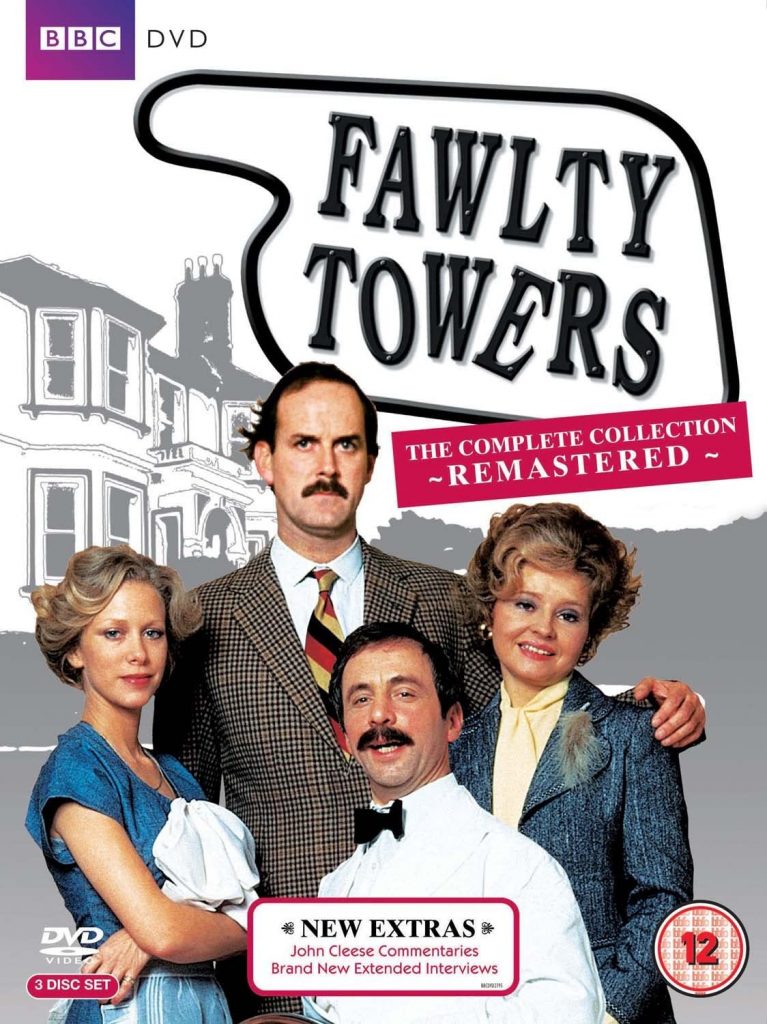

Although he was always strangely noticeable in mediocre 1970s sitcoms such as Oh, Father! (with Derek Nimmo) – and played a hapless builder, O’Reilly, in the second episode of Fawlty Towers – he distinguished himself, and first endeared himself to a television audience, in RTÉ’s 1980 series Strumpet City, based on James Plunkett’s novel about the Dublin lock-out, also starring Peter O’Toole, Cyril Cusack and Peter Ustinov. He played “Rashers” Tierney, the colourful basement dweller, and counted the role his favourite (alongside Krapp). He maintained his popularity in two long-running television soaps both set in fictional villages in County Wicklow: Glenroe, the first RTÉ series to be shown (from 1991) with Irish subtitles, and the BBC’s Ballykissangel, screened from 1996 to 2001. Kelly worked consistently in films from 1969, when he played the vicar in a funeral scene in The Italian Job, starring Michael Caine. He appeared again with Caine in Terence Young’s spy movie The Jigsaw Man (1984).

His most notable film appearances in the 1990s were in two delightful Irish movies: Mike Newell’s Into the West (1992), scripted by Jim Sheridan, with Gabriel Byrne and Ellen Barkin, in which he played an old storyteller in a community of travellers; and Kirk Jones’s Waking Ned (1998) in which, with his best friend, played by Ian Bannen, he engineered a small village’s response to an unexpected lottery windfall and set about fooling the claims inspector. He also boasted of becoming an overnight sex symbol as he went naked on a motorbike.

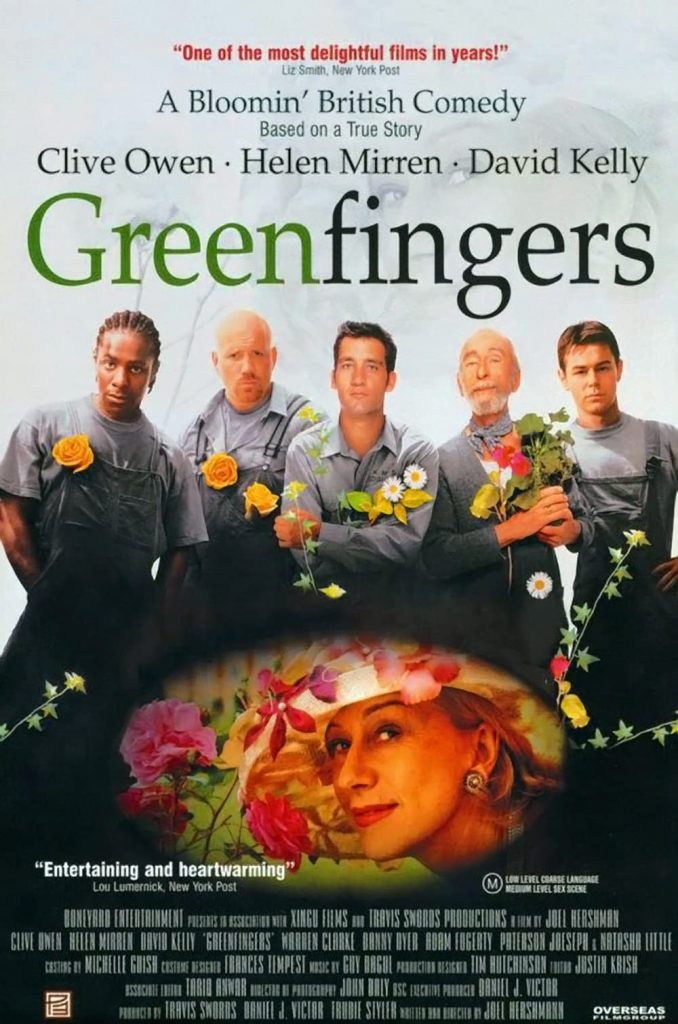

He appeared with Kevin Spacey in the Irish crime caper Ordinary Decent Criminal (1999), and with Helen Mirren and Clive Owen in Greenfingers (2000). Kelly’s last major movie appearance was in Matthew Vaughn’s Stardust (2007).

He is survived by Laurie and their children, David and Miriam.

• David Kelly, actor, born 11 July 1929; died 12 February 2012

His obituary in “The Guardian” by Michael Coveney can also be found online here.

Dictionary of irish biography.

Kelly, David (1929–2012), actor, was born on 11 July 1929 in the Rotunda hospital, Dublin, the son of Edward Kelly, a clerk, and his wife Hannah (née O’Connor). He grew up in Dublin, first in Fairview and then Clonskeagh, and attended Synge Street CBS, which he described as a savage place. Wanting to be an artist, he studied briefly at the National College of Art in 1946, and relaxed throughout his life by painting, exhibiting at least twice. Also keen from an early age on acting, he sang during his childhood at the Gaiety Theatre with the Rathmines and Rathgar Musical Society. His father diverted him into training first as a calligrapher, giving him a trade to fall back on.

Going to the Abbey School of Acting in 1950, Kelly got bit parts in pantomimes and then in avant-garde productions at the Gate Theatre and in fringe venues. A notable early casting was in the first staging of ‘The quare fellow’ by Brendan Behan (qv) at the Pike Theatre (November 1954). Initially working as a calligrapher in an advertising agency, Kelly found it prevented him from rehearsing and quit his day job, commencing a period of financial struggle. From the mid 1950s he attracted good reviews in supporting parts and branched into comic roles in musicals and satirical revues. Versatility was essential for the revues in particular, and he broadened his range acting in everything from slapstick to Chekhov.

In 1959 he undertook a role where every movement and vocal inflection carried meaning, when cast as the sole performer in the first Irish production of ‘Krapp’s last tape’ by Samuel Beckett(qv). Although Kelly was far younger than the 69-year-old Krapp, it was a critical triumph, as his lugubrious, prematurely wizened features enabled him to pass as much older and suited the existentialist tragicomedy of Beckett. (Kelly’s gauntness resulted from a stomach ulcer contracted in 1949, which forced him to eat and drink sparingly and led him increasingly to play hard up or otherwise distressed characters. Even after being cured of the ulcer, he rarely exceeded seven stone, despite standing 5 foot 10 inches.)

A dedicated professional, who loved his craft without being precious about it, he was a precise and reliable performer with an engaging yet understated stage presence. Although never short of work, primarily with the Gate, he acted in only one play before 1980 at Ireland’s national theatre, the Abbey, and his lack of leading-man appeal and the exigencies of the small Irish market frequently saddled him in marginal, hackneyed roles in second-rate productions. He made a career out of transcending these limitations, generally by embracing clichéd material with a zeal that flirted with parody, but developed into something more layered and authentic. Off stage, he dressed like a dandy and spoke in a camp thespian accent, regaling listeners with his biting wit and stock of theatrical anecdotes. Forever eyeing the next job, he charmed the show-business fraternity with his vivacious and courteous manner.

Kelly married (1961) fellow actor Laurie Morton, from Harcourt Street, Dublin, who starred in RTÉ’s popular soap opera Tolka row(1964–8) before largely retiring from acting to raise their son and daughter. They spent the period immediately after their wedding performing in the London theatre scene, but settled in Dublin, living first in Dundrum and then permanently in Goatstown. The marriage was a happy one except for a time from the late 1960s when Kelly had an operation that cured his stomach ulcer and celebrated by becoming an alcoholic. By March 1972 the drinking was undermining his acting so he checked into a clinic and conquered his addiction.

During the 1960s he drifted into better-paid television work, becoming a mainstay of RTÉ drama and comedy. He was cast in numerous failed comedy series into the late 1990s, the sole success being his straight-man role alongside Ireland’s most popular humourist, Jimmy O’Dea (qv), in O’Dea’s your man (1963–4). Featuring the ruminations of two railway men in a stationmaster’s box, this series of twenty-six episodes (none of which survives) consisted of unrehearsed, one-take performances involving occasional ad-libbing from a script by Brian O’Nolan (qv). Arising from this, Kelly performed into the 1970s in lavish Gaiety Theatre pantomimes and revues headlined by O’Dea and by O’Dea’s main collaborator, Maureen Potter (qv).

Kelly’s first British television credit was in 1951; there followed cameos and guest appearances in popular shows such as Doctor Who (1963), Emergency Ward 10 (1965), Public eye (1966) and Z cars(1972). By the late 1960s he was earning most of his income from playing Irish eccentrics in British comedies and one-off dramas, often written by his friend Hugh Leonard (qv). He was the self-flagellating Cousin Enda for the second and third series of the Leonard-scripted BBC sitcom Me mammy (1970–71) before becoming a recurring character during 1973 in both the soap opera Emmerdale Farm and the ecclesiastical comedy Oh, Father!.

In 1975 his memorable nine-minute turn playing the incompetent builder O’Reilly in an episode of the highly popular sitcom Fawlty Towers established him as the British public’s favourite Irish buffoon. The interaction between John Cleese’s tightly wound Basil Fawlty and Kelly’s amiably feckless O’Reilly delighted viewers, and by the late 1990s Kelly estimated he had received nearly thirty residual cheques from repeats shown worldwide. He again played an inept, and in this case drunken, Irish builder in Cowboys (1980–81), and made nearly fifty appearances in Robin’s nest (1977–81) as Albert Riddle, a simple-minded, one-armed Irish kitchen hand who became the show’s main source of humour, turning an uninspired comedy into a ratings triumph and Kelly into a minor celebrity in Britain. Brushing off accusations of perpetuating ethnic stereotypes, he observed that the likes of John Cleese were never criticised for portraying ludicrous Englishmen.

He stamped himself indelibly on the Irish public’s consciousness in 1980, by stealing the plaudits from a stellar cast as the crafty tramp Rashers Tierney in RTÉ’s landmark, internationally lauded historical miniseries Strumpet city. The role was of a sort he had done many times, normally for laughs, but in a career-defining performance he invested the broken, ultimately doomed Rashers with depth and pathos, later recalling that ‘he was the very essence of Dublin, the enormous dignity … despite the rags’ (Film Ireland, Feb.–Mar. 1999). Kelly had long coveted the part, having years earlier extracted a promise from James Plunkett (qv), author of the original book, that he would play Rashers in any television series.

Television commitments in Britain meant that, to his regret, Kelly went for stretches of two to three years during the 1970–80s without appearing on stage in Dublin. One notable foray was his double act with his friend Ray McAnally (qv) in ‘The midnight court’ at the Peacock Theatre (1983), which exemplified his scope for bouncing off more forceful performers and switching seamlessly between farce and tragedy. Back on British television, he excelled playing the deposed shah of Iran’s extravagantly obsequious adviser in the sprawling six-part ITV satire Whoops Apocalypse (1982), before beautifully capturing the angst of a man shorn of his political faith as one of Stalin’s henchmen in the darkly humorous Channel 4 film Red monarch (1983).

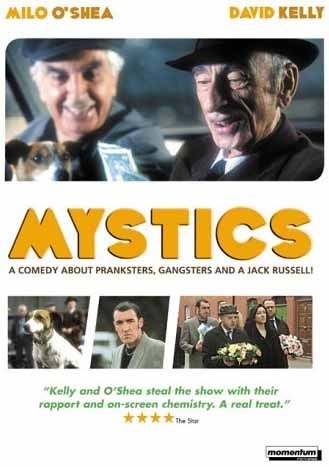

After his British television career petered out following his role in the Bruce Forsyth comedy Slinger’s day (1986–7), he concentrated on Irish-based theatre and television, becoming a semi-regular on RTÉ’s flagship soap opera Glenroe. He reprised his role in ‘Krapp’s last tape’ to great acclaim at the Gate Theatre (1991), and subsequently in productions in Barcelona (1992) and Melbourne (1997) and on three US tours with the Gate, the last in 2000. This incarnation was less grotesque and pathetic than his 1959 version, with Krapp emerging instead as mean, ludicrous but unbowed. Having previously performed together in 1950s Dublin comedy revues and in the British sitcom Me mammy, Kelly and Milo O’Shea (qv) put on a tour de force at the Gate in the light-hearted Neil Simon comedy ‘The sunshine boys’ (1996); every night the bombastic O’Shea strove to outdo and surprise Kelly, who weaved and countered with serpentine aplomb.

Kelly had been appearing in movies since 1958, mainly ones shot at least partly in Ireland. His film credits included eye-catching cameos in Girl with green eyes (1964) and Ulysses (1967), briefly playing a vicar in the British comedy caper The Italian job (1969), and a supporting role in the quirky and risqué Quackser Fortune has a cousin in the Bronx (1970). Later he cherished opportunities to spend a day doing a scene with Laurence Olivier in the dreadful British spy thriller The jigsaw man (1983), and to act for director Roman Polanski in the visually impressive commercial flop Pirates (1986). From the late 1980s he illuminated a string of forgettable Irish movies, the exception being the charming fantasy Into the west (1992).

His long-standing status as a well-respected jobbing actor was transformed when he was cast in Waking Ned Devine (1998), a British- and French-financed comedy set in Ireland but shot in the Isle of Man on a shoestring budget. Cheerfully peddling hoary clichés of rural Ireland, the film was redeemed by its feel-good spirit and the chemistry between its elderly co-stars, Kelly and Ian Bannen. Kelly’s exuberant yet subtly measured physical comedy won him the International Press Academy’s Golden Satellite Award for best comedy actor and a nomination for the prestigious Screen Actors’ Guild award. The most famous scene in the movie, and of his career, had him naked atop a speeding motorcycle, all protruding collarbones, elbows and ribs, his ferret-like features a rictus of panicked resolve. Although disdained by Irish critics, the film was a surprise hit in the USA and proved popular when released in Britain and Ireland in 1999 as Waking Ned.

Much in demand thereafter, he appeared in a succession of British and American movies of varying quality, mainly playing loveable oldsters. Amongst other roles, this late-career cinematic flowering saw him develop a surprisingly good on-screen rapport with former football hard man Vinny Jones in Mean machine(2002), revert to a broad Irish stereotype in The calcium kid(2004), relish playing a villain in The Kovak box (2006), and reunite twice with Milo O’Shea for the bleak Rough for theatre 1 (2000) in the Gate’s ‘Beckett on film’ project and the knock-about farce of Mystics (2003). He also distinguished himself alongside stars such as Kevin Spacey in Ordinary decent criminal (2000), Helen Mirren and Clive Owen in Greenfingers (2000), and Robert De Niro and Michelle Pfeiffer in Stardust (2007). In 2005 he was widely praised for his performance in the biggest role of his career, when cast as Grandpa Joe, whom he modelled on his own father, in the children’s movie Charlie and the chocolate factory; he bonded with the film’s lead, Johnny Depp, over their shared love of jazz.

Retiring in 2009, he suffered latterly from Alzheimer’s disease, and spent his last months at the St John of God Hospital, Stillorgan, Co. Dublin, where he died on 12 February 2012. His remains were cremated at Mount Jerome crematorium.

GRO (birth cert.); Ir. Press, passim, esp.: 9 July 1952; 4 May 1964; 14 Oct. 1965; 25 Dec. 1973; 26 May 1980; 19 May 1990; 30 Sept. 1991; Ir. Independent, passim, esp.: 17 June 1953; 9 Feb. 1961; 29 Sept. 1980; 4 Dec. 1998; 18, 20 Mar. 1999; 8 Aug. 2000; 30 July 2005; 13, 14, 16, 17 Feb. 2012; Ir. Times, passim, esp.: 31 Mar. 1959; 26 Dec. 1960; 14 June 1961; 9 Mar. 1968; 17 Sept. 1988; 7 Oct. 1991; 25 July 1996; 5 Dec. 1998; 3 Apr. 1999; 30 July 2005; 14, 17, 18 Feb. 2012; Dublin Opinion, May 1959; Hibernia, May 1959; Times, 4 May 1961; 15 Feb. 2012; Sunday Independent, 9 Feb. 1969; 16 Sept. 1973; 6 Apr. 1980; 12 Feb. 1989; 9, 16 June 1996; 21 Mar. 1999; 30 June 2002; 31 July 2005; 19 Feb., 14 Oct. 2012; 7 Apr. 2013; Carolyn Swift, Stage by stage (1985); Philip B. Ryan, Jimmy O’Dea: the pride of the Coombe(1990); Phyllis Ryan, The company I kept (1996); Guardian, 31 Oct. 1998; 19 Mar. 1999 (interview); 13 Feb. 2012; Film Ireland, Feb.–Mar. 1999; Michael Gray, Stills, reels and rushes: Ireland and the Irish in 20th century cinema (1999); Beckett Circle, xxiii, no. 1 (fall, 2000); Morris Bright, Fawlty Towers: fully booked (2001); Deirdre Purcell (ed.), Be delighted: a tribute to Maureen Potter (2004); Sunday Tribune, 24 July 2005; Graham McCann, Fawlty Towers: the story of the sitcom (2007); Hot Press, 24 Sept. 2008 (interview); Scotsman, 15 Feb. 2012; Independent (London), 17 Feb. 2012; Aodhan Madden, Fear and loathing in Dublin (2015 ed