DAILY TELEGRAPH” OBITUARY IN 2020

Jon Whiteley, who has died aged 75, was a highly distinguished and exceptionally revered museum curator, whose career in the world of art was preceded by an entirely unexpected backstory as an Oscar-winning child star in the 1950s.

Jon James Lamont Whiteley was born on February 19 1945 in Monymusk, Aberdeenshire. His father, Archie, was a headmaster, with the result that Whiteley grew up with an unusual respect for education, which was to prove decisive in determining the course of his later life.

At the age of six, his rendition of “The Owl and the Pussy-Cat” on a BBC radio broadcast from his school was heard by a talent scout, who grasped his potential, and over the next few years he made five feature films. Their casts alone make it clear that these were major productions.

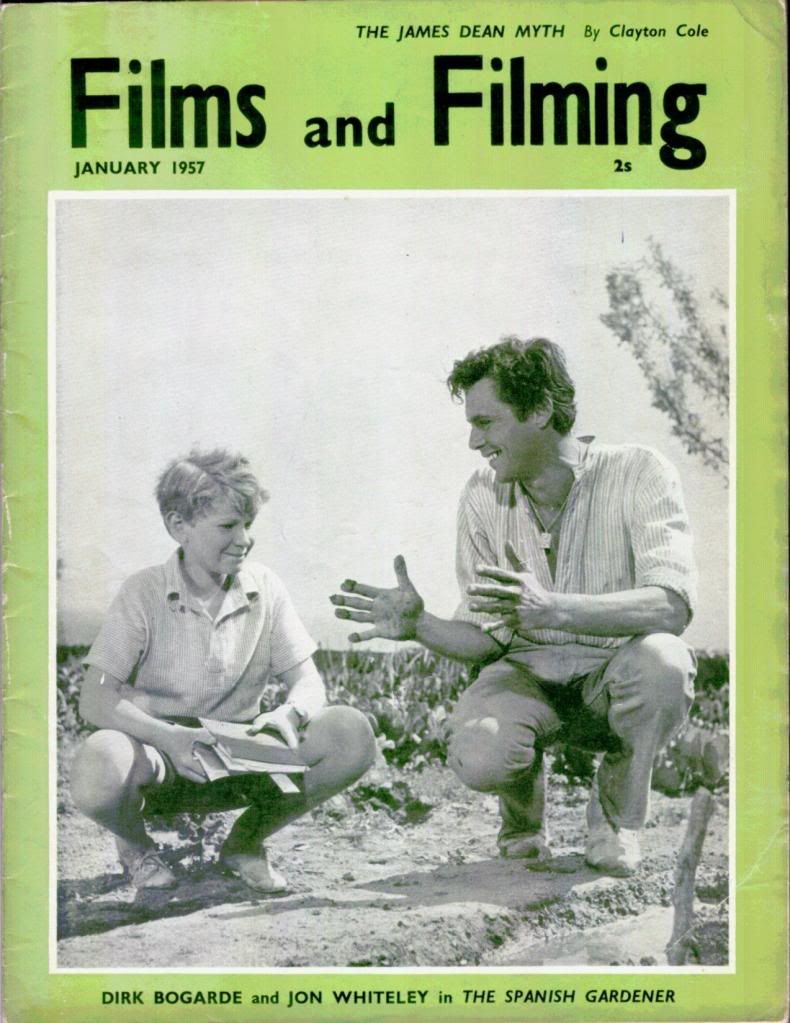

Two – Hunted (1952) and The Spanish Gardener (1956) – saw him teamed up with Dirk Bogarde. In The Weapon (1956) he played opposite Herbert Marshall, while in Moonfleet (1955) he co-starred with Stewart Granger, George Sanders and Joan Greenwood. Most remarkably, the film brought him together with one of the greatest directors of all time, Fritz Lang, whose career stretched back to the birth of silent cinema in the 1910s.

However, Whiteley’s appearance in The Kidnappers (1953) was to have an even more spectacular aftermath, because at the Oscars for 1954 he and his fellow child star, Vincent Winter, received honorary awards for – in the words of the citation – their “outstanding juvenile performances”.

That year, On the Waterfront swept the board, winning Best Picture, Best Actor, and much else besides, but while Elia Kazan, Marlon Brando and others were basking in the applause at the ceremony, it was business as usual for Whiteley back in Scotland.

It was term-time and his parents saw no point in going all that way to collect the Oscar in person. It arrived through the post, and Whiteley was, above all, struck by its ugliness. In a recent interview he remarked: “It is at home somewhere, but I don’t think it is a particularly attractive object. It has no great charm.”

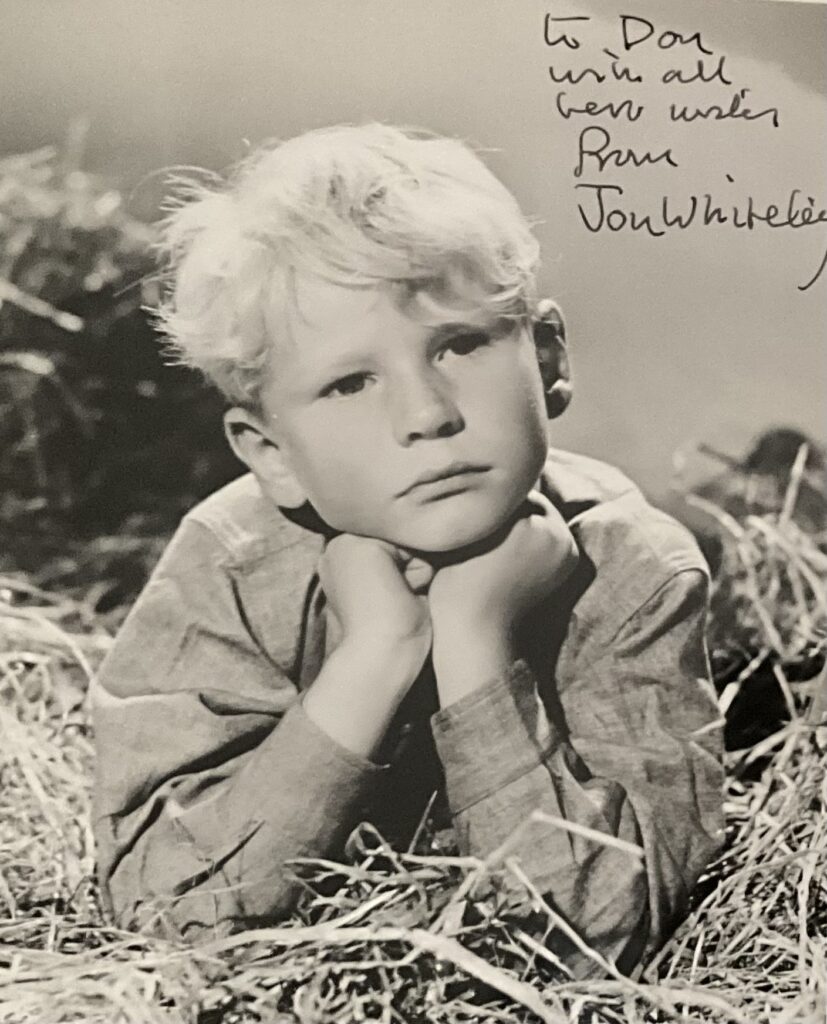

The opposite might be said of its recipient, although what is so remarkable about his beguiling screen presence in those five films is precisely that it seems to have nothing to do with acting. He seems to be quite unaware of the presence of the camera and just gets on with being himself, worlds removed from the stomach-churningly knowing cuteness which was, alas, all too common even among the best child stars.

Happily, courtesy of DVDs and the internet, these performances are now readily accessible in a way that could not even have been dreamt of in the 1950s.

Apart from a couple of television appearances – an episode of Robin Hood in 1957 and one of Jericho in 1966 – that was the end of the chapter. It had always been agreed that at the age of 11 his serious education should begin, and – apart from a mild regret at no longer having a chauffeur – he never looked back. The afterlives of child stars are often downhill all the way, but there are exceptions. What is certain is that few have achieved as much as Whiteley in their adult lives.

Whiteley was an undergraduate at Pembroke College, Oxford, and never left the dreaming spires. He stayed on and took a DPhil with Professor Francis Haskell on the 19th century painter Paul Delaroche, one of whose most famous paintings – The Princes in the Tower – could almost be a still from a Jon Whiteley movie.

After a brief spell as an assistant curator at the Christ Church Picture Gallery, from 1975 to 1978, he moved to the Ashmolean Museum as an assistant keeper in the Department of Western Art, remaining there until his retirement in 2014.

Nobody has ever known the Ashmolean’s collections the way Whiteley did, and he was the inevitable first port of call for numberless colleagues both within and beyond the museum. He was also a wonderfully welcoming presence in the print room; for novices, initial visits to such places can be intimidating, but Whiteley treated everyone with the same exquisite courtesy.

His other great achievement at the Ashmolean was in connection with his role in setting up the Education Department. A notoriously modest man, he did admit: “I am most proud of that.”

An old Oxford joke has a don answering the question “What is your field?” with the riposte “I do not have a field. I am not a cow.” For all that Whiteley was a great authority on his first love, French art, and was appointed a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2009, his scholarship was heroically wide-ranging both across space and time in an age of increasing specialisation.

In the context of France, as well as books on Ingres and Lucien Pissarro, he moved effortlessly beyond the 19th century, writing the catalogue of an important Claude Lorrain exhibition at the British Museum, cataloguing the French drawings at the Ashmolean in two volumes, the first being devoted to Étienne Delaune and the second covering the period from Poussin to Cézanne. A few months ago he just managed to complete his catalogue of the museum’s holdings of French paintings after 1800 before his final illness.

As if all this were not enough, he produced memorable books on Oxford and the Pre-Raphaelites in 1989, and on the Ashmolean’s collection of stringed instruments in 2008.

Fittingly, since an initial ambition to be a painter had led him to his chosen métier, he wrote with all the flair and understanding one might hope for from an artist. A compelling and much-loved lecturer, he also won undying devotion from his undergraduate – and, perhaps especially, postgraduate – students.

Jon Whiteley first met his wife Linda, also an art historian, in a library when they found themselves reaching for the same book. Marrying in 1972, they gave the impression of remaining of one mind for evermore, and had a son and daughter.

Jon Whiteley, born February 19 1945, died May 16 2020

The times obituary in 2020

In the early Fifties female cinema-goers took to their hearts a new Scots star who would go on to win a seldom-awarded special Oscar. His hobbies, reported the newspapers, included drawing cartoons and playing with his toy space gun, and he was known for his beautiful, gentle speaking voice, a face that often looked on the verge of tears, and his thick golden hair. When he finished filming his first film, and his co-star, Dirk Bogarde, asked him what he would like as a farewell gift, he asked for a monkey from Harrods.

As a child star in postwar British cinema, Jon Whiteley brought out the maternal side in women everywhere from the moment he was first seen onscreen at the age of five — giving an astonishingly natural performance in Hunted in 1952. At that time, his role as an abused orphan abducted by a man on the run because he had witnessed a murder was the longest part any child had played on the British screen. It took him away from his Aberdeenshire home for 15 weeks and earned him rave reviews.

Whiteley loved working with “jolly and generous” Bogarde. Then one day a scene was being shot in which Bogarde had to shake the child and ask him why he had done something wrong. Whiteley, thinking that his new pal had turned against him, immediately burst into violent tears and was inconsolable for several minutes. Bogarde then gently explained that it was all a great game: that this was what acting meant

For The Kidnappers (1953), a period drama about two recently orphaned brothers who begin a new life on a Nova Scotia farm with their God-fearing Scottish grandparents (played by Duncan Macrae and Jean Anderson), Whiteley was teamed with another young Aberdonian, Vincent Winter. British director Philip Leacock — with whom, along with Bogarde, Whiteley would be reunited for The Spanish Gardener (1956) — would become known for getting the best out of child actors, and his two young stars exceeded expectations when they both won a special “Juvenile Oscar” for their unaffected and beguiling performances.

Jonathan James Lamont Whiteley was born in 1945 in the village of Monymusk in Aberdeenshire. His mother, Christine (née Grant), was an elocution coach and his father, Archie, was headmaster of the village school, which Whiteley and his two younger sisters, Fleur and Marsoli, attended. Whiteley was discovered when he recited Edward Lear’s The Owl and the Pussycat in his playground for a school programme on the Scottish Children’s Hour. An actor who heard him remembered that Charles Crichton, the director, was looking for a child for his film Hunted. Soon afterwards Whiteley took a screen test at Pinewood Studios. He was such a natural that Crichton reworked the backstory to accommodate his lilting Scottish accent: the child he played had originally been a Londoner

Whiteley’s parents were not too keen on an acting career for their son but his father, thinking that the filming process might prove a good discipline, agreed to his making one film per year until he was 11 – and then focusing on his education. His short career took him to Hollywood, where he worked for the great director Fritz Lang on Moonfleet (1955) and it gave him a taste of the phoneyness as well as the fabulous trappings of fame. He did not get to attend the Oscars ceremony to collect his award in person, because it took place during term time. But, given how little the physical statuette appealed to this future distinguished art historian — “I never liked it. It’s rather art deco” — it is perhaps just as well.

Whiteley was an undergraduate at Pembroke College, Oxford, and stayed on to take a DPhil in the revival in painting of themes inspired by antiquity in mid-nineteenth century France. French art was his first love, and he had been a francophile since his childhood when the family would drive from Aberdeen across Europe, camping in Versailles en route. He was delighted and honoured when the French government appointed him a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2009.

He married Linda (née Wilson), also an art historian, in 1972. They had met in a library. She survives him, along with their children, Flora, a painter, and William, an English teacher and editor, and their grandchildren, Alfred and Owen Whiteley Rollen.

In 1978, after a brief spell as an assistant curator at the Christ Church Picture Gallery in Oxford, Whiteley moved to the Ashmolean Museum as assistant keeper in the Department of Western Art, remaining there until his retirement in 2014 but, as Dr Alexander Sturgis, director of the Ashmolean pointed out, continuing to contribute his expertise and knowledge in numerous ways right up to his recent illness. He was most proud of having helped set up the education department, and was a hugely popular figure.

Whiteley enjoyed reliving the heady days of chauffeur-driven limos and transatlantic trips. In recent years, his films began to appear regularly on the television channel Talking Pictures TV. For one interviewer, in 2017, he even, reluctantly, exhumed from a drawer his baby Oscar. It had not worn nearly as well as its owner — who, thanks to his tousled forelock of hair, was still instantly recognisable as the mini heart-melter of the Fifties