Lionel Blair was born in 1931 in Montreal. His family came to England where he was an infant. His films include “The World of Suzy Wong” in 1960 with William Holden and Nancy Kwan. His sister was the actress Joyce Blair.

“Guardian” interview in 2013:

I was born in 1932 and we grew up in Stamford Hill, north London. When the war began we were evacuated to Oxford – just me and my sister and my mother – while my dad stayed in London working. I remember playing in the garden with my younger sister, Joyce, and we saw a German plane crash. My father said, “If that can happen there, what’s the point of being in the country away from each other?” So we came home to Stamford Hill.

My father’s parents were Russian and he was the archetypal north London barber – “Something for the weekend, sir?” and all that. From an early age Joyce and I were taken to the pictures, – it was always Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers or Shirley Temple. We used to go home and try to copy them. That’s how we learned to tap dance.

We were Jewish but not orthodox. During the war, Dad brought bacon home and we’ve eaten it ever since. I think that was frowned upon by certain people in the community when they got a sniff of our bacon sandwich. But every Friday we had chicken and my mother would light candles.

My father died when I was 13. He had a hernia and thought he’d cured it but he hadn’t and it became strangulated and he had a duodenal ulcer as well. He went into an operating theatre and came out dead. It was a huge shock for the whole family. It changed everything. It was the first time I’d ever thought, I’m never going to see him again. It was so awful and I don’t think I’ve ever experienced a loss like it.

After Dad died, I had to grow up artificially fast. We had no money so I had to work. I’d started work as a boy actor and my dad had been thrilled about that, but I became too old for little boy parts and too young for grown-up parts. I could dance so I got into musicals and started performing with Joyce. But just as we were becoming well known on television, my mother died and so we were orphans. Then Joyce met her first husband, Eddie, so I was on my own.

I will have been married to Susan for 46 years in March. The secret of a successful marriage is memories. You must have memories together. That’s why my dad insisted that we went everywhere together, so we could talk about things. I’m so lucky to have a wife who is a nest builder. Her nest is the most important thing in the world to her.

When my first son was born I was driving home and I suddenly said to Susan, “We’ve got another life in our family,” and it was just wonderful. My children are 43, 40 and 30 and the youngest is still at home. We’ve got three grandchildren too and it’s heaven. I love them to distraction.

My children didn’t like seeing me on the telly. When they first started going to school – a state school – having a famous father was not the best thing in the world. They were teased because I was a dancer and my persona didn’t help. Then we sent them to Italia Conti [Academy of Theatre Arts], which was a different sort of thing altogether and there were kids there who were almost jealous because they had a famous father. We’ve got a very, very normal family, and for me everything comes back to family. If they’re sad, I’m sad. I want them to be happy all the time.

• Lionel Blair performs a one-man show at London’s Hippodrome Casino on 23 March, hippodromecasino.com. Box office: 020-7769 8866

The above “Guardian” interview can also be accessed online here.

The times obituary in 2021.

After a long day’s filming Lionel Blair was enjoying a drink in the bar on Blackpool pier when word came that a desperate man was threatening to commit suicide by jumping into the sea. It sounded like a stunt for The End Of The Pier Show, which Blair had just finished filming with the comedian Alan Carr. Yet the incident was all too real and by the time the celebrities arrived at the scene, the poor chap was hanging by his fingertips and seconds away from plunging to his death. We got his hand and said, ‘Come on, you don’t want to die. You can’t do that. Listen to us’,” Blair recalled. “He said, ‘No I want to go’. So I grabbed one arm and Alan got the other and we hauled him up.

Blair was approaching 80 at the time but it was a rare heart-in-mouth moment of danger in a showbiz career that was noted for its middle-of-the-road safeness rather than its challenging edginess.

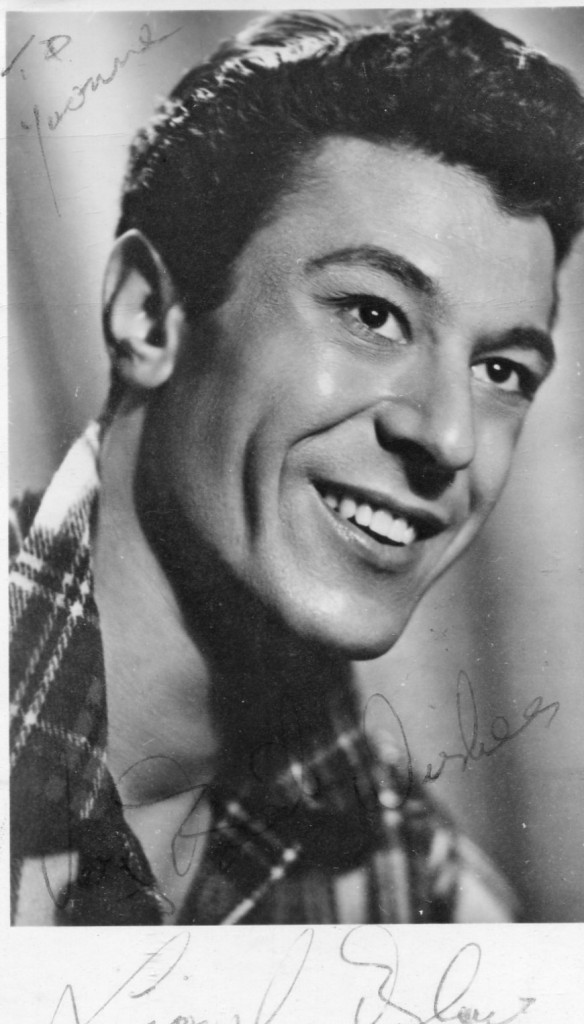

With his big, bouffant hair, gleaming teeth and perma-tan, Blair was as cheesy as they came but his relentless energy sustained him over seven decades, beginning with his first youthful performances singing and dancing to keep up the spirits of those taking shelter from German bombs during the Blitz

An old-school family entertainer, Blair sang a bit, danced a lot and acted on stage and screen. He hosted TV game shows and talent contests and appeared in countless pantos. Eventually he became famous simply for being Lionel Blair, making it difficult to recall for what it was exactly that we were meant to remember him. His name even managed to enter the language as cockney rhyming slang for flares.

He began in the age of variety but slotted seamlessly into the 21st-century world of reality TV, known to younger generations for wearing a PVC suit and being handcuffed to the Made In Chelsea star Ollie Locke as a Celebrity Big Brother contestant in 2014.

Blair was 85 at the time and Locke was six decades his junior but he matched the younger man for x-rated language, revealing a rather different side to his character when he went off-script. “Everyone was so shocked, but it was brilliant. I’m sick of being that nice Lionel Blair,” he said.

An ability not to take himself too seriously was one of his endearing traits. Seven years earlier he had appeared in Extras, a TV sitcom written by Ricky Gervais, playing himself as a has-been entertainer struggling to save his career by appearing on Celebrity Big Brother.

His theatrical campness and general flamboyance led many to surmise incorrectly that he was gay. He once appeared on The Kenny Everett Television Show chained up half-naked in a dungeon, being whipped by the show’s host and apparently enjoying every second of it.

It led to him becoming the subject of a running gag on the BBC radio spoof panel game I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue in which the show’s chairman Humphrey Lyttelton delivered outrageously smutty double entendres about Blair’s alleged gayness. At first he took it in good humour but he eventually snapped.

“If it was just me that had to deal with it I wouldn’t care. But it’s my family it upsets,” he complained. “You should always speak good of the dead. He’s dead. Good,” he remarked after Lyttelton died. To what extent he was joking was unclear but the comment only encouraged Lyttelton’s successor, Jack Dee, to continue the relentless ribbing. That the gay jibes had got to him was evident during a charity cricket match organised by Michael Parkinson when he punched a spectator who called him a “fairy”. He laid claim in his younger years to what he called “an active bachelor life”, squiring numerous models and actresses, including Joan Collins. He even said that he had caught the eye of Errol Flynn’s wife while at a party at Ernest Hemingway’s house in Spain. A hard act to follow, presumably. A fling with a dancer, meanwhile, resulted in a son being born in 1957, after the relationship had ended. He declined to see either. “I behaved like an absolute bastard,” he recalled. “I was too busy, too cruel.

He was in his 40th year when he eventually married Susan, a model who was dating his best friend and whom he met at a dinner party. They married six weeks later and their union endured for more than half a century, despite a tabloid exposé in which he admitted a series of one-night stands. “I’m not a flirt, but I’m always friendly. It’s very lonely on tour,” he explained. A lachrymose man, mention of his wife and family often brought tears to his eyes.

He is survived by their three children, Daniel, Lucy and Matt. Family holidays were taken in Marbella, where he bought a second home, but the sniggering rumours about their father led to the children being bullied at school. He then enrolled them at the Italia Conti stage school and all three went on to become actors.

He was born Henry Lionel Ogus in Montreal, Canada, to Russian immigrants in 1928, although for most of his career he claimed to have been born in 1931. His father, Myer Ogus, was a barber and his mother, Della (née Greenbaum), a housewife. When he was two the family moved to London, where his younger sister, the actress Joyce Blair, was born. The antisemitism of the time generated by Sir Oswald Mosley’s fascist blackshirts led his father to change the family name.

Growing up in Stamford Hill, he was taught to observe the Sabbath without following the full orthodoxy: bacon sandwiches were a childhood favourite.

When war broke out, he was evacuated to Oxford with his mother and sister but when they watched a German plane crash from the garden of their new home, his father concluded that they might as well return to London. His biggest treats as a child were visits to the art deco Regent cinema in Stamford Hill, where he and his sister watched Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers films. “We used to go home and try to copy them. That’s how we learnt to tap dance,” he recalled. During air raids they took shelter in Manor House Tube station, where Lionel and Joyce sang and danced for those camped out on the platforms until the all-clear was sounded.

When he was 13, his father died during what should have been a routine operation for an ulcer. Forced to become the family breadwinner, he left school and took to the boards. As his voice had not broken, he began with girlish parts.

Later he toured with the Savoy Players, did summer seasons as a double act with Joyce and danced in West End musicals.

Forming his own dance troupe, he became a regular on 1950s television variety shows, just as the medium was establishing itself as a fixture in British homes. What he regarded as the defining moment of his career came when he appeared as a double act with Sammy Davis Jr at the 1961 Royal Variety Performance. Their turn started with a sketch in which a snooty Savile Row shop assistant (Blair) offered a brash American customer (Davis) instruction in how to carry himself like a English gentleman. By the end it had become an exhilaratingly thrilling tap-dance routine with Blair matching the lightning-footed Davis step for wonderful step.

They became firm friends and Davis gave him a silver dollar inscribed: “To Lionel Blair. Because I dig you.” He carried it in his wallet for the rest of his life. Decades later Blair was still using the black and white archive footage of their performance to introduce his one-man show.

Davis was also called in to service as a family counsellor. After an acrimonious argument with her brother, Joyce had emigrated to Los Angeles in the late 1970s, claiming that she wanted to “escape being Lionel Blair’s sister”. They had not spoken for a dozen years but when both visited Davis, who was dying of cancer, he persuaded them to be reconciled.

Film work included an appearance in the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night, during which he had a memorable night out in a casino with Brian Epstein, who won £89,000. Blair enjoyed a gamble but was not in Epstein’s league as a high-roller. When he lost £300 at the tables one night he decided it was a mug’s game and gave it up for good.

Always careful with his money, he had instant recall of how much he had been paid for every show he did. The 1980s, when he was appearing frequently on the TV game shows Give Us a Clue and Name That Tune, was a particularly bounteous time. “I was recording four shows a day and getting four salaries, which worked out very nicely,” he noted. Surprisingly, he found pantomime was almost as lucrative. The popular view may be that panto is for B-list celebrities, but Blair reported that he could earn £100,000 for a six-week run. “Why do you think the stars do pantomime?” he said. “Buttons, Dick Whittington, Jack in Jack and the Beanstalk. Aladdin . . . I did them all.”

It was the proceeds of a panto season that persuaded him to buy a Rolls- Royce, although characteristically it was a secondhand model for which he paid £12,000, and he soon sold it when he discovered that “one little thing goes wrong and it costs you a fortune.

He was also paid handsomely for a series of lager adverts in which he delivered the less than immortal line, “A pint of Harp,please chief”, although he claimed he had never been drunk in his life. “The drug thing I stayed well away from too and that saved me a lot of money,” he said. Despite prostate cancer he was still working when he turned 90. Looking back he admitted that there were times when he wished the world had taken him more seriously. After all, he pointed out, he had performed in Shakespeare, Stoppard and Ayckbourn. Yet ultimately he was content to have been an old-fashioned song-and-dance man. “Everybody said: ‘Give us a twirl, Lionel’,” he recalled. “That’s what they wanted, so that’s what they got.”

Lionel Blair, actor, dancer, choreographer and television presenter, was born on December 12, 1928. He died on November 4, 2021, aged 92.