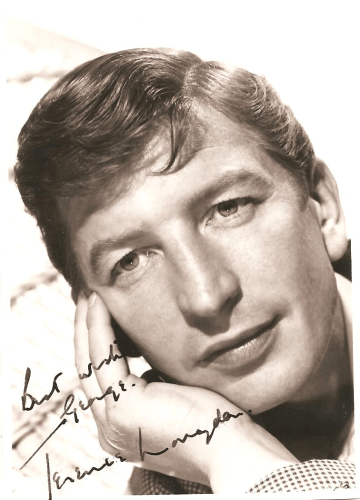

Robert Newton was born in Dorset, England in 1905. He began acting at 16 with Birmingham Repertory Company. His first film was “Farewell Again” in 1937. His major films include “Jamaica Inn”, “Oliver Twist”, “The High and the Mighty”, “The Beachcomber”, “This Happy Breed” and his last film “Around the World in 8o Days”. His film career and indeed life was cut short by chronic alcoholism which led to his death from a heart attack in 1956 aged just fifty. His best remembered role is as the definite Long John Silver in Walt Disney’s “Treasure Island”.

TCM Profile:

To a generation of moviegoers, English actor Robert Newton is the personification of Long John Silver; he played the pirate in the Disney classic Treasure Island (1950), its sequelLong John Silver (1954) as well as in a 1950s TV series The Adventures of Long John Silver. But Newton’s career wasn’t limited to swashbucklers. He appeared in classic works by Shakespeare and Shaw and Dickens. He co-starred with British acting greats such as Charles Laughton and Laurence Olivier and he worked with a talented list of directors from Alfred Hitchcock to David Lean. For an actor best remembered as a pirate, Newton enjoys an extremely impressive filmography.

Robert Newton was born June 1, 1905 in Shaftesbury, Dorset, England. His mother was a writer and his father a painter. Newton began acting at an early age and made his stage debut at the age of 15. His first appearance was in Henry IV (Part One) for the Birmingham Repertory Theatre. Newton stayed with the company for three years, working as an assistant stage manager, and taking roles in Twelfth Night and Romeo and Juliet. He made his London debut at Drury Lane in 1924 in London Life. Newton’s star rose when he was cast in Noel Coward’s Bitter Sweet in 1929. And just two years later, Newton made his Broadway debut, filling some pretty big shoes in the process Newton succeeded Laurence Olivier in another Coward production, Private Lives.

Newton made his first film in 1932 with the small British drama Reunion. He then returned to the stage for several years, appearing in Hamlet at the Old Vic and in other plays like Miss Julie. Newton’s next film came in 1937 when he played the Captain of Caligula’s Guard in I, Claudius. The film, which was never completed due to overwhelming production problems, was directed by Josef von Sternberg and starred Charles Laughton and Merle Oberon. Newton would make two more films with Laughton: Hitchcock’s last British film before immigrating to America, Jamaica Inn (1939), and Vessel of Wrath (AKA The Beachcomber) (1938). The latter film was based on a W. Somerset Maugham novel and, in 1954, Newton would star in a second film version of the story. This time, Newton took the role played by Laughton in the original.

In 1937, Newton had his first lead role in the film The Squeaker where he played a cat burglar. He also took a leading part in the original film version of Gaslight (1940) and he played husband to a pioneer aviatrix in Wings and the Woman (1942). Newton then returned to the theatre for a string of stage adaptations: he appeared in Shaw’s Major Barbara (1941) with Rex Harrison and Wendy Hiller; the family drama This Happy Breed (1944) by Noel Coward; and Shakespeare’s Henry V (1944), directed by and starring Laurence Olivier. Newton followed up his stage run with a turn in Carol Reed’s IRA suspense-drama Odd Man Out (1947).

Newton gave a memorably frightening performance as the villainous Bill Sikes in David Lean’s production ofOliver Twist (1948). He also played the merciless Inspector Javert in Les Miserables (1952) and, as previously noted, sailed under a pirate flag in Treasure Island, the film that marked the peak of his popularity. Newton was one of the top ten moneymakers in British cinema (as voted in the Motion Picture Herald-Fame Poll) from 1947 to 1951. After Treasure Island Newton played another pirate Blackbeard, in Blackbeard the Pirate(1952). In 1954, he returned to Treasure Island in a sequel called Long John Silver.

One of Newton’s last films was the high flying John Wayne suspense-adventure The High and the Mighty(1954). He made his final feature appearance in Around the World in 80 Days (1956); Newton lived just a month after shooting was complete. Officially, the cause of death was a heart attack, but Newton’s excessive drinking was certainly a factor. He died March 25, 1956.

by Stephanie Thames

The above TCM Profile by Stephanie Thames can also be accessed online here.

A tribute to Robert Newton here.