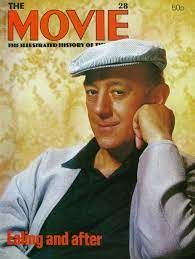

Alan Bates obituary in “The Independent” in 2003.

Alan Bates was a brilliant versatile actor who made many fine films in both Britain and the U.S. He started his career on film with “The Entertainer” with Sir Laurence Oliver. He was part of that great group of young British actors including Michael York, Albert Finney, Michael Caine, Tom Courtney and Terence Stamp who sored to stardom in the 1960’s. He went to the U.S. to make “An Unmarried Woman” and “The Rose”. He continued to make many fine films and act on the stage until his death in 2003.

His obituary by Alan Strachan from “The Independent”:

The quiet man among his generation of British stage and film stars, Alan Bates had a charisma, with a potent suggestion of banked and often ambivalent inner emotion, which marked him out as a leading actor of rare quality.

He had an undervalued comic gift – his performance in Clive Donner’s filmNothing but the Best is as slyly funny as anything in an Ealing classic – but the brooding power behind such stage portrayals as Redl in John Osborne’s A Patriot for Me and the title role in Simon Gray’s Butley; and, on screen, Gabriel Oak in Far From the Madding Crowd, Anthony Quinn’s English friend in Zorba the Greek, or Julie Christie’s lover in The Go-Between, inevitably will be best remembered.

Bates was a Derbyshire boy and returned there often; he helped open a new Playhouse in Derby in 1976 by leading a production of Chekhov’s The Seagull. His grammar-school education in Belper began his love-affair with Shakespeare; his theatre-loving mother also often took him to the Derby Little Theatre Club. He trained for the stage at Rada at a time when a new breed of British dramatists were creating the chances for young actors such as Bates, Albert Finney, Tom Courtenay and Kenneth Haigh to bring distinctive voices to the stage alongside the well-bred tones of a West End then still in thrall to the deferential, well-made play.

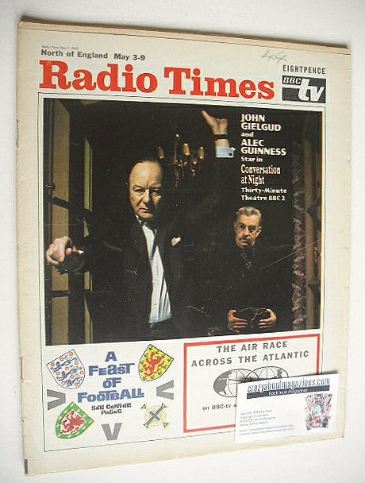

More or less straight out of Gower Street, Bates was snapped up by George Devine for the new ensemble based at the Royal Court Theatre directed by Devine and his young associate director Tony Richardson. The English Stage Company bridged the generations from the pre-war glory days of companies led by John Gielgud and Michel Saint-Denis to the emergent new wave, its acting talent ranging from Devine, Peggy Ashcroft and Rachel Kempson to Bates, Haigh, Joan Plowright and Mary Ure, with its designers including Gielgud’s Motley (with “Percy” and Sophie Harris) and the younger Jocelyn Herbert and Alan Tagg.

Bates thrived in the “family” atmosphere at Sloane Square. It was there to a large extent, surely, that he absorbed the values of the company ideal so important to his standards as an actor subsequently. Always much loved and deeply respected by colleagues, he had when an established star the rare gift of being the centre of a company without dominating it.

In that unpredictable first 1956 ESC season, Bates had a good run of roles, following Simon in Angus Wilson’s comedy The Mulberry Bush with Hopkins in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (surprisingly tepidly received critically) and then Cliff Lewis in the premiere of Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, which justified the whole ESC enterprise as a forcing-ground for new talent. Often in production simply a feed to Jimmy Porter, opposite Kenneth Haigh’s Jimmy, Bates as Cliff found a dogged, often baffled and torn devotion at the heart of the role, most powerfully in its suggestion of Cliff’s unvoiced love for the Alison of Mary Ure. After further ESC work, Bates made a highly praised Broadway début with Look Back in Anger (Lyceum, NY, 1958), an experience which provided him with many splendid anecdotes featuring the provocative behaviour of its producer, themonstre sacré David Merrick.

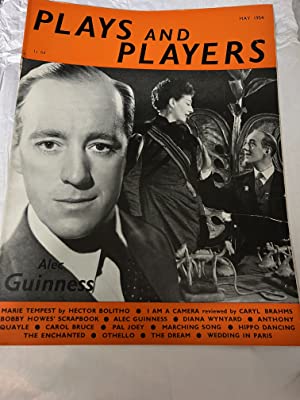

Back in London, Bates startled even those who had marked him out as a gifted younger actor with the edgy emotional tension which he brought to Edmund, the consumptive younger brother of the haunted Tyrone family at the centre of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night (Globe, 1958) in the play’s British premiere. Even in a glittering company including Anthony Quayle, Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies and Ian Bannen, this was excitingly risky high-wire acting, refreshingly free from the costive restraint of so much contemporary work.

That sense of the primal also stamped Bates’s Mick in the first production of Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker (Duchess, 1960 and Lyceum, NY, 1961); there was a dangerous glint, something feral at the heart of this wide boy, that was distinctly unsettling. Bates stayed on in New York after The Caretaker. By now an established London and Broadway star, he was headlined in a new play by the popular comedy dramatist Jean Kerr, Poor Richard (Helen Hayes, 1964), but in trying to extend her range Kerr’s tone was uncertain, although Bates’s endearingly self-deprecating performance carried the play to a moderate success.

Broadway offers were abundant, and movies in England and Hollywood were also luring him. Having launched his film career with The Entertainer (1960) for Tony Richardson, he followed it with beautifully gauged performances in Whistle Down The Wind(1961) as the mysterious Messiah-figure and as the trapped anti-hero of Alan Sillitoe’s A Kind of Loving (1962) for John Schlesinger. Bates, however – as would be evident throughout his career – was never particularly keen to follow the easiest or most lucrative path.

Returning to England and to the theatre he took on the challenge of Arnold Wesker’s The Four Seasons (Saville, 1965). A two-hander love-story packed with dense, often heightened language, this somewhat unexpected departure by Wesker baffled most critics and the play was a commercial flop but, opposite Diane Cilento, Bates was in formidable form, coping with the dramatist’s technical demands (he had to make strudel-dough on stage) with as much aplomb as he handled a difficult text.

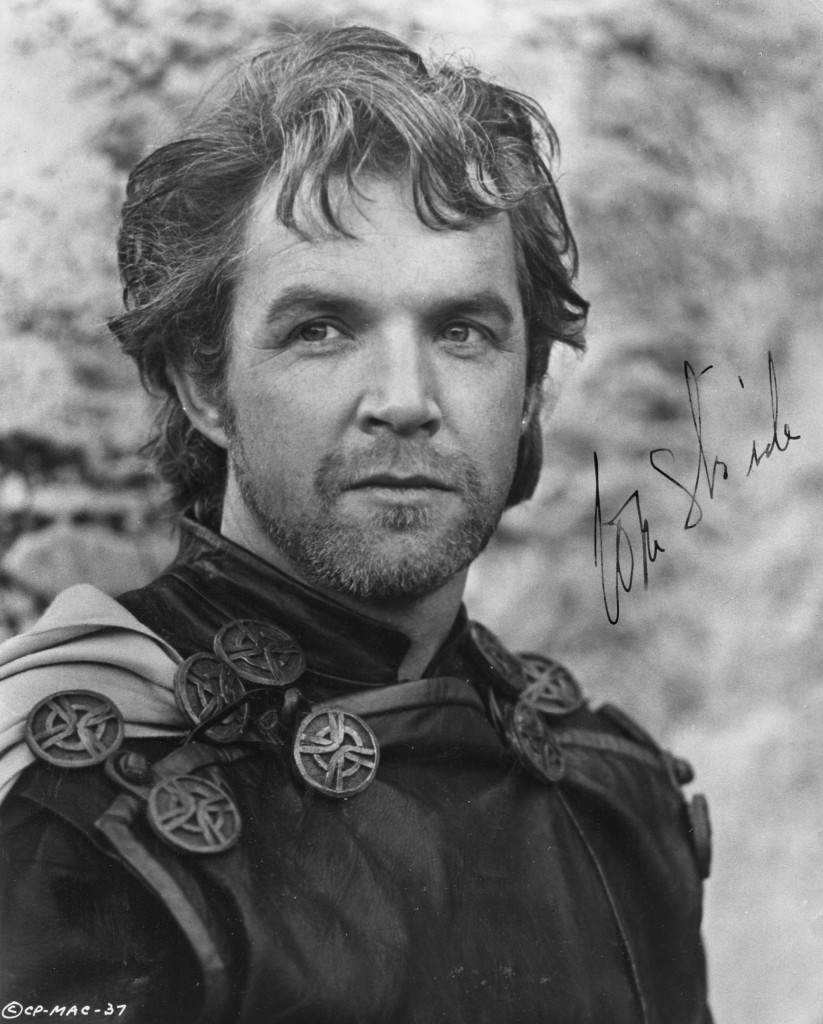

He then moved off to Canada to take on classic work at Stratford Ontario; in its 1967 season he was an unusually dark Ford, eaten by self-loathing jealousy, in The Merry Wives of Windsor and appeared even darker in the title-role of Richard III, the sardonic joker, flicking off his jests and quips with whiplash zest, collapsing into hideous and terrified despair. This remarkable double was followed by his truthfully understated playing in David Storey’s family play In Celebration (Royal Court, 1969) under Lindsay Anderson.

With his unselfish, touching screen performance in Zorba the Greek(1964), Bates became a genuinely international star. For a brief period he concentrated on movies, but deliberately kept ringing the changes, reluctant always to succumb to the siren-lures of the Hollywood Hills. He combined quirky British choices – Nothing But the Best (1964) in which he and Denholm Elliott gave master-classes in the timing of cool comedy, and the surprise-hit of Georgy Girl(1964) – with off-beat American films such as The Fixer (1968, for which his performance rightly brought him an Oscar nomination) and foreign work including King of Hearts (1967) as well as two of the most successful British pictures of the later 1960s, Far From The Madding Crowd (1967) and Ken Russell’s Women in Love (1969). InWomen in Love, he and Oliver Reed were ideally cast as D.H. Lawrence’s contrasted heroes, both actors committing wholeheartedly (aided by generous swigs of vodka) to the famous nude wrestling scene.

The 1970s saw some remarkable performances from Bates as he alternated between stage and screen. His long association with the work of Simon Gray, usually directed by Harold Pinter, began withButley (Criterion, 1971 and NY, 1972) which won him Evening Standard Best Actor and Tony Awards. He was mesmerising as Gray’s troubled don, totally inhabiting the character’s acid wit and mordant irony and never once playing for sympathy; in Butley’s more reflective moments, the performance fused some of the qualities which had distinguished Bates’s Hamlet (Cambridge Theatre, 1971). This was in a somewhat antiseptic production but Bates’s performance was remarkable for its sense of inner solitude; this Hamlet was almost paralysed into emotional immobility by the loss of a clearly adored father, freighting his scene opposite Gertrude (Celia Johnson) with a powerful mixture of resentment and love.

The Gray/Bates/Pinter team had an even bigger success withOtherwise Engaged (Queens, 1975) with Bates at the centre of a Rolls-Royce cast as the music-loving Simon, a man with an almost monastic dedication to the practice of detachment, humanised by Bates with his uncanny ability to suggest subterranean lets and hindrances in his characters. He gave an equally subtle portrayal as the tutor at the heart of Life Class which happily returned him to Sloane Square (Royal Court and Duke of York’s, 1974) by David Storey, another dramatist to whose writing Bates always brought a special affinity. Another Simon Gray piece, a less than thrilling thriller, Stage Struck (Vaudeville, 1979) gave Bates the chance to play a juicily bravura, devious character, which he clearly enjoyed and which he made extremely successful at the box-office.

His next noteworthy stage appearance was not until 1983 when he played the tortured Redl in Osborne’s epic play, A Patriot For Me(Chichester and Haymarket), unrevived since its Royal Court premiere. Ronald Eyre’s production was a lucid reappraisal of a flawed masterpiece with Bates’s performance its vital centre. The sexual confusion of the character was movingly traced but Bates also crucially brought to his performance the sense of a character who felt himself also an outsider socially, fatally nudging him into his career of espionage.

After a wonderfully bold black comedy take on Strindberg’s The Dance of Death (Riverside Studios, 1985), a Pinter double-bill ofVictoria Station and One for the Road (Lyric Studio, Hammersmith, 1985), a selflessly loyal performance in Peter Shaffer’s strenuousYonadab (National Theatre, 1985) and another Gray, Melon(Haymarket, 1987), Bates returned to ensemble-based theatre with a West End season of Chekhov’s Ivanov in tandem with Much Ado About Nothing (Strand, 1989). He and Felicity Kendal had a lovely partnership, full of quicksilver raillery in the Shakespeare, Bates wryly funny as a soldier surprised by late- flowering love, splendidly contrasting with the volatile, shambolic emotional mess that he created of Ivanov.

Bates had not acted for the Royal Shakespeare Company since a disappointing Taming Of The Shrew in 1974. He returned in 1999 to take on a role he seemed born to play – Antony in Antony and Cleopatra, opposite Frances de la Tour. The production was cordially loathed by many, with its opening scenes of graphic oral sex and the well-intentioned but in practice faintly risible notion of dead bodies rising up to walk off stage. Undoubtedly the production has its flaws, but its leading players brought to it an exhilarating emotional energy and erotic charge; Bates was immeasurably moving in those perilous later scenes as Antony faces his end. Sadly, illness meant his withdrawal from the same season’s Timon of Athens, another role to which he was ideally suited.

A good number of Bates’s later films after the New Cinema resurgence of the 1960s were, as he owned, poor stuff. After the triumph of The Go-Between for Joseph Losey (1971) there were some genuine turkeys, not least the Bette Midler vehicle The Rose(1979), with a heavily bearded Bates looking somewhat uneasy as the rock diva’s manager, while the truly terrible Michael Winner remake of The Wicked Lady (1984) was even worse.

Bates’s best later films tended to be in low-budget or independent pictures – in the underrated Merchant-Ivory Quartet (1982), he had a delightful, rumpled avuncular charm as a Ford Madox Ford figure and he was also impressive in the film version of Patrick McGraph’sThe Grotesque (2000).

After a period of some disappointing films, a time also marked by personal sadness (the early death of one of his twin sons, closely followed by his wife’s death) and illness, Bates’s later work happily saw him in full flower once more. In one of his final films – Robert Altman’s Gosford Park (2002) – his performance of unctuous rectitude was a highlight even in an unusually lustrous cast, while on stage he had a New York success opposite Eileen Atkins in Yasmina Reza’s delicately poised two-hander The Unexpected Man (NY, 2001); he returned to match that success for one last Broadway appearance with Fortune’s Fool (NY, 2002) in which he had previously appeared at Chichester (1996).

Bates’s comic gift perhaps had its best opportunities on the smaller screen; even the most rabidly loyal Mitfordists had to concede that in the most recent television version of Love In a Cold Climate (2001), his Farve, splenetically disappearing behind the useful carapace ofThe Times or boggling in bug-eyed disapproval at the sight of any potential suitor for his daughters, was the real thing.

Other memorable Bates television appearances included the son in John Mortimer’s autobiographical A Voyage Round My Father(1983), quizzically tender opposite Laurence Olivier’s glorious English eccentric, which appeared in the same year as one of his supreme performances, in Alan Bennett’s An Englishman Abroad. Based on the meeting in Moscow between the actress Coral Browne (who played herself) and the defected traitor Guy Burgess in 1959, John Schlesinger’s film revolved round Bates’s glorious performance.

Looking like a debauched Botticelli angel and seemingly gleefully unrepentant, still full of the camp, mandarin Cambridge style of the 1930s, cannily and gradually Bates revealed the hollow man below, lost and loveless in his chosen promised land. The film ends with Browne, as requested, arranging for a new suit to be made by Burgess’s old Savile Row tailors; the final shots of a seemingly revived and squeaky-clean Burgess encased in his new pinstripes, with bowler and tightly-furled brolley, beaming as he strides jauntily through the Moscow crowds, to the strains of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “To Be an Englishman”, are unforgettable.

Alan Strachan’s obituary from the “Independent” can also be accessed online here.