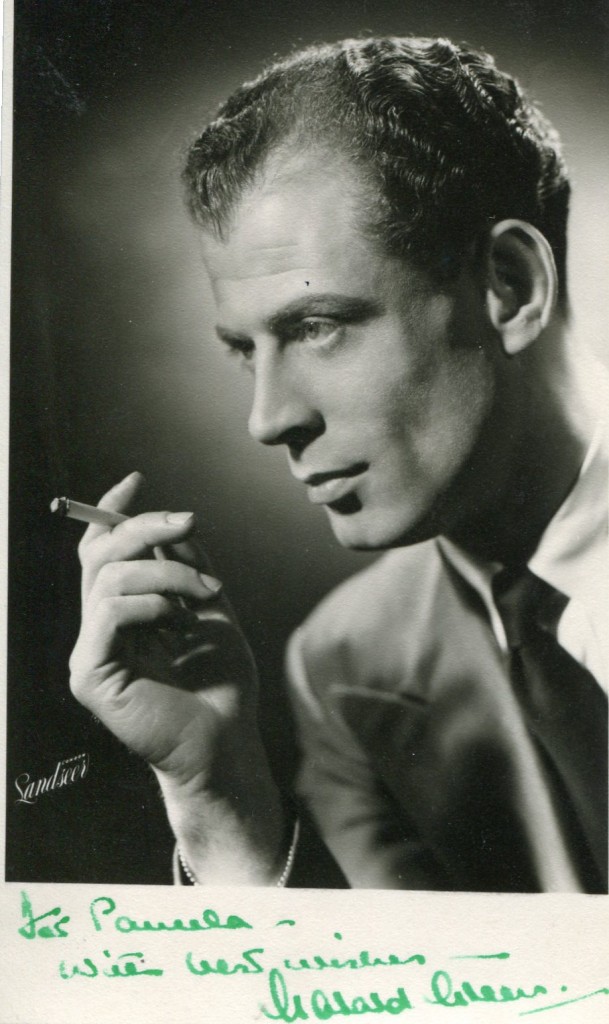

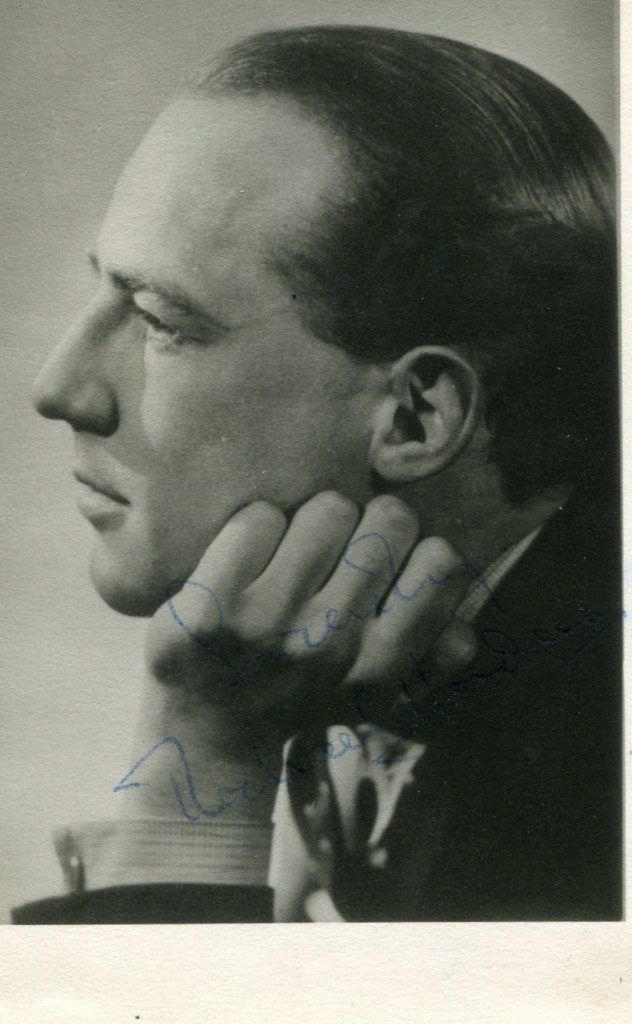

Michael Hordern was born in Hertfordshire in 1911. He was a profilic character actor on film with his contributions on film becoming more distinguished as he aged. Among his films are “Passport to Pimlico” in 1949, “The Spanish Gardner” in 1956 and “Sink the Bismarck”. In 1972 he went to the U.S. to make “The Possession of Joel Delaney” with Shirley MacLaine and Perry King. He was knighted in 1983 and died in 1995.

“Telegraph” obituary:

Though he described himself as “a bear of very little brain”, Hordern had a special talent for portraying intellectual eccentrics, and one of his greatest triumphs was as George, the moral philosopher in Tom Stoppard’s Jumpers at the National Theatre in 1972 (he reprised the part in 1977). The embodiment of a tortured metaphysician, he strode about the stage with his hands variously thrust behind his hips, locked behind his back or rubbing furiously at his neck.

Hordern took time to establish himself as a classical actor. The turning point came in 1950, when he played Nikolai Ivanov at the Arts Theatre, and was critically acclaimed for the intelligence and sensitivity of his performance. Two years later Glyn Byam Shaw invited Hordern to appear at Stratford, where he won plaudits as Caliban in The Tempest (opposite the Prospero of Sir Ralph Richardson, who terrified him), as Jacques in As You Like It, as Sir Politick Would-Be in Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist and as Menenius in Coriolanus, a performance Kenneth Tynan pronounced “great”.

The peak of Hordern’s Shakespearean career came in 1969, when he played Lear in Jonathan Miller’s production at the Nottingham Playhouse and Old Vic. There was no hysteria passio in his interpretation; he presented Lear as a sharp, peremptory pedant, who cursed his daughters as though delivering a legal sentence. The disintegration of Lear’s mind was conveyed as much by well-timed silences as by raving, and snatches of demented wisdom emerged with peculiar poignancy.

Hordern’s reputation as a classical actor never inhibited him from taking less prestigious roles. He had a lovely, warm and slightly querulous voice, and enjoyed working for radio; he particularly relished the role of Paddington Bear. By contrast Gandalf, in J R R Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings seemed “a bit of a slog”.

On television Hordern was outstanding in Mortimer’s Paradise Postponed (1986), in which he played the Rev Simeon Simcox, the gentleman Socialist who leaves his fortune to a local lad, and thus sets the revolting Leslie Titmuss on his way to becoming a Tory minister.

Hordern did not sniff at the financial rewards of advertising, and once observed with amazement that in two hours making a commercial in a studio he had earned more than in an entire season at Stratford. This was irresistible to a man who claimed not to enjoy the company of other actors, preferring to spend every spare moment casting flies from the river bank.

The third of three brothers (though he would gain an adopted sister), Michael Murray Hordern was born at Berkhamsted on Oct 3 1911. His maternal grandfather invented Milk of Magnesia; his father (who numbered several clerics among his ancestors) was an officer in the Royal Indian Marines; and one of his brothers, Peter, would play rugby for England. There was no theatrical tradition in the family, in which young Michael’s lachrymose tendencies earned him the sobriquet Streaks.

When he was five, his mother joined his father in India, and he was dispatched to Windlesham, a preparatory school near Brighton, where he stayed for term and holidays alike. He had already discovered the delights of fishing, and at school developed a keen interest in drama. At Windlesham, Hordern recorded in his autobiography A World Elsewhere (1993), “I was rather a pet. In fact, I think I’ve been rather too much of a pet all my life.”

He went on to Brighton College, where he starred in Gilbert & Sullivan productions. Meanwhile the family had moved to a remote house on Dartmoor, where there were few neighbours, and none that the Hordern parents cared to acknowledge. On leaving Brighton College, Hordern found a job in a prep school at Beaconsfield; after only a term, though, his teaching career was brought to an abrupt halt by a bout of polio.

When he recovered, he took a job with the Educational Supply Association, which supplied schools with desks and blackboards. Gradually amateur dramatics began to take up most of his time and in 1936 Hordern decided to take his chance as a professional actor. The next year he was engaged at the Savoy Theatre as assistant stage manager and understudy to Bernard Lee in Night Sky. He believed that he was a better actor for not having gone to drama school. “It appals me!” he said. “To Hell with it! Some are born to act, some are not. I regret not learning fencing, which may affect one’s Hamlet, but that’s about it.”

After appearing as Lodovico in Othello at the People’s Palace Theatre, Mile End Road, he joined a tour to Scandinavia, playing Henry in Outward Bound and Sergius in Arms and the Man. Flush with this success he went off to chase a beautiful Polish girl in Warsaw. On his return he played leading roles for the Rapier Players at Bristol.

When war broke out Hordern volunteered for the Navy and served as a gunner in the merchant ship City of Florence, which was taking ammunition supplies to Alexandria. The convoy was attacked by U-boats and Hordern saw five ships sunk in as many minutes. Later he was posted to the aircraft carrier Illustrious as Flight Direction Officer, in charge of deploying fighter cover against incoming enemy aircraft. He proved exceptionally good at this new military science, and is still remembered with affection in the Fleet Air Arm.

Off Salerno in 1943 an enemy flying boat stumbled on Illustrious. Hordern dispatched the carrier’s fighters, and later announced the flying boat’s destruction over the ship’s broadcast system, quoting Hamlet’s lines on discovering he has stabbed Polonius: “Thou wretched, rash, intruding fool, farewell. I took thee for thy better.” Hordern later took part in the ferocious fighting in the Pacific, off Okinawa. He rose to lieutenant commander, and after the war worked at the Admiralty.

Having eased himself back into acting with some radio work, he took the lead in one of the first post-war television productions, Andre Obey’s Noah. On stage he played Torvald Helmer in A Doll’s House at the Intimate Theatre, Palmers Green. Later in 1946 he appeared in Dear Murderer at the Aldwych; he was killed by Terence de Marney in the first act. At the end of the year he was engaged at Covent Garden as Bottom in Purcell’s The Fairy Queen, and had a song specially written for him by Constance Lambert. Hordern was the gallant hero in Noose by Richard Llewellyn (Saville, 1947).

The next year he went to the Q Theatre at Kew, where he was in Peter Ustinov’s The Indifferent Shepherd, and Pastor Manders in Ibsen’s Ghosts. At the end of the year he triumphed at Stratford in one of his favourite roles, Mr Toad in The Wind in the Willows. After appearing in A Woman in Love, Stratton, and Ivanov, Hordern played Macduff in Macbeth, directed by Alec Clunes.

In 1951, at the Arts, he tackled Paul Southman, the Methuselah-like lead in John Whiting’s Saint’s Day – a role he would reprise at the same theatre 14 years later. In 1953 Hordern joined the Old Vic to play Polonius to Richard Burton’s Hamlet, in a notably successful production which was presented before the Danish royal family at Elsinore. Hordern also attracted favourable notices as Parolles in All’s Well That Ends Well, as Malvolio in Twelfth Night, and as Prospero in The Tempest. A production of Andre Roussin’s Nina, in 1955, was chiefly remarkable for Hordern’s screaming rows with the director, Rex Harrison – though consolation came in the shape of Coral Browne. “I kept falling in love,” confessed Hordern. “It is a common complaint among actors. You cannot be at such close quarters, mind and body, without being sorely tempted.”

In 1958 Hordern played an important part in John Mortimer’s first theatrical success, a double bill comprising What Shall We Tell Caroline and Dock Brief (Lyric, Hammersmith and Garrick). Dock Brief was a precursor of the Rumpole television series – though Hordern’s court hack, suffused with self-doubt, had little in common with the barrister portrayed by Leo McKern.

After an ill-fated foray to New York with the disastrous Moonbirds, Hordern rejoined the Old Vic to play the lead in Macbeth. The reviews were not kind: “half the time,” observed one critic, “he cringed like an Armenian carpet-seller in an ankle-length black dressing gown.” Hordern joined the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Aldwych for the 1962-63 season, appearing as a homosexual dress designer in Harold Pinter’s The Collection. He was also the Father in Strindberg’s Playing With Fire, Ulysses in Troilus and Cressida, and Herbert Georg Beutler in Friedrich Durrenmatt’s The Physicists.

In 1967 Hordern starred with Celia Johnson in Relatively Speaking at the Duke of York’s – Alan Ayckbourn’s first commercial success. Enter a Free Man at the St Martin’s Theatre in 1968 offered the actor his first part in a Tom Stoppard play – that of George Riley, the ever-optimistic inventor. Hordern returned to the Aldwych to play Tobias in Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance, and in 1970 gave a consummate performance as a lecherous parson in David Mercer’s Flint at the Criterion.

Hordern’s triumphs in King Lear and Jumpers were followed, in 1972, by a gruff account of John of Gaunt in Richard II at the National. His next critical success came three years later when he played a judge who abandons his family for a gogo dancer in Howard Barker’s Stripwell at the Royal Court.

In 1976 he returned to Stratford, where his Prospero evoked only modest rapture. But he thoroughly enjoyed himself as Don Amado in Love’s Labour’s Lost, mincing about the stage in great stacked heels. The next year he was well reviewed as the lead of Ronald Harwood’s adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold – though the play closed soon after transferring to London.

As Hordern entered his eighth decade his stage appearances began to dwindle and he was distressed by his inability to remember lines. But he was a superbly choleric Sir Anthony Absolute in the National Theatre’s 1983-84 production of Sheridan’s The Rivals, feverishly denouncing his son while tucking into a boiled egg. In 1990 he played a schoolmaster in Bookends, Keith Waterhouse’s adaptation of Craig Brown’s witty spoof of the correspondence between Rupert Hart-Davis and George Lyttleton.

Hordern’s last part in the West End was the crusty judge Sir William Gower in Pinero’s Trelawney of the Wells at the Comedy (1992). Hordern’s film career had begun before the war with The Girl in the News (1939), and eventually extended to more than 60 titles. If he never made as great an impression on celluloid as on stage, this was because, by his own admission, he tended to choose film parts not so much for their artistic potential as for the money and for the locations – Pacific Destiny (1956) being a good example.

Among his better films were Passport to Pimlico (1949), in which he was a hyperactive policeman; The Spanish Gardener (1956), in which he played an embittered British Consul neurotically jealous of his son’s affection for the gardener (Dirk Bogarde); and I Was Monty’s Double (1958). Hordern’s association with Richard Burton helped him to secure roles in Alexander the Great (1956), Cleopatra (1963) and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1966). He also appeared in The Bed Sitting Room (1969), Sink the Bismarck (1960), Futtock’s End (1969), England Made Me (1973), The Slipper and the Rose (1976) and Gandhi (1982).

Hordern gave a succession of wonderful performances on television, in O Whistle and I’ll Come to You (1968); Tartuffe (1971); The History Man (1981); Rod and Line (1982); The Wind in the Willows (1983); Memento Mori (1992), and Middlemarch (1994). He also played Lear twice on television, in 1975 and 1982.

On radio Hordern was so brilliant in the title role of What Ho, Jeeves! (1973) that The Sunday Telegraph’s critic suggested dropping all the other actors so he could read the original text on his own. Recently, he was Old Jolyon in The Forsyte Chronicles (1990) and the Player King in Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet (1992).

He was appointed CBE in 1972 and knighted in 1983. He married, in 1943, Eveline Mortimer, whom he met when they both belonged to the Rapier Players at Bristol; she died in 1986. They had a daughter.

The above “Telegraph” obituary can also be accessed online here.