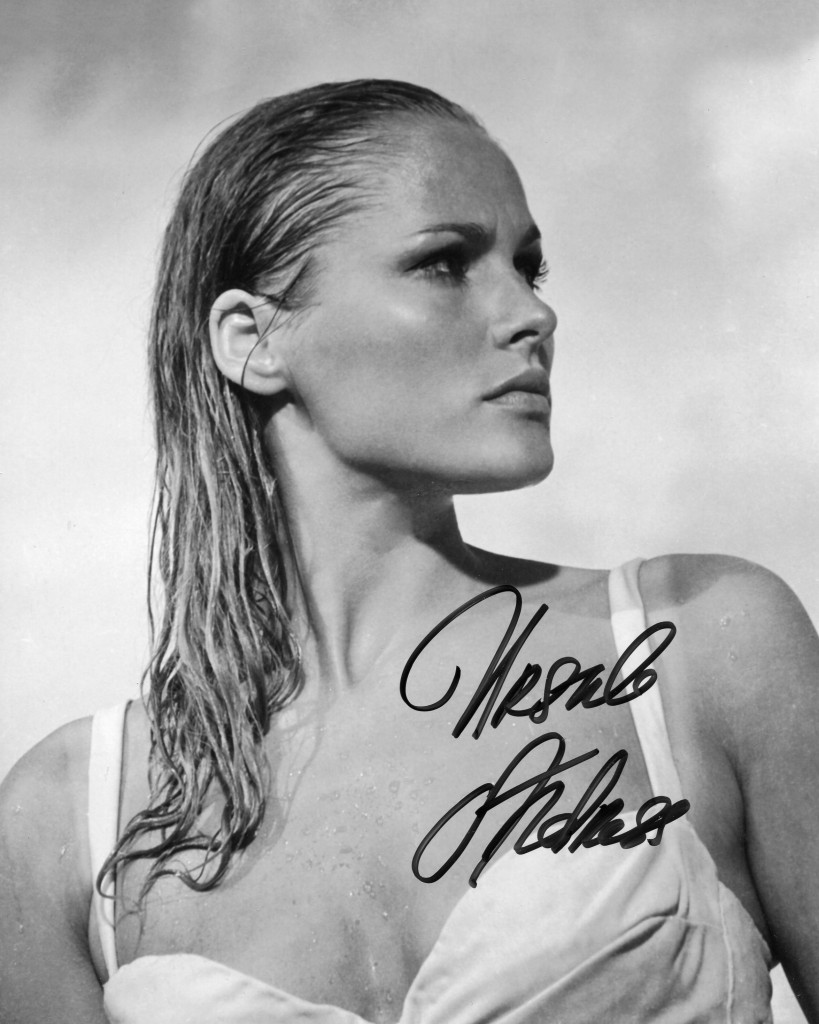

“Lynx-eyed, vivacious Ursula Andress was the nearest thing to a cartoonist’s version of a 1960’s sex symbol. In the 1960’s she complied with her image to a series of roles that bore little resemblance to reality”. – Barry Monush in “The Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors”. (2003)

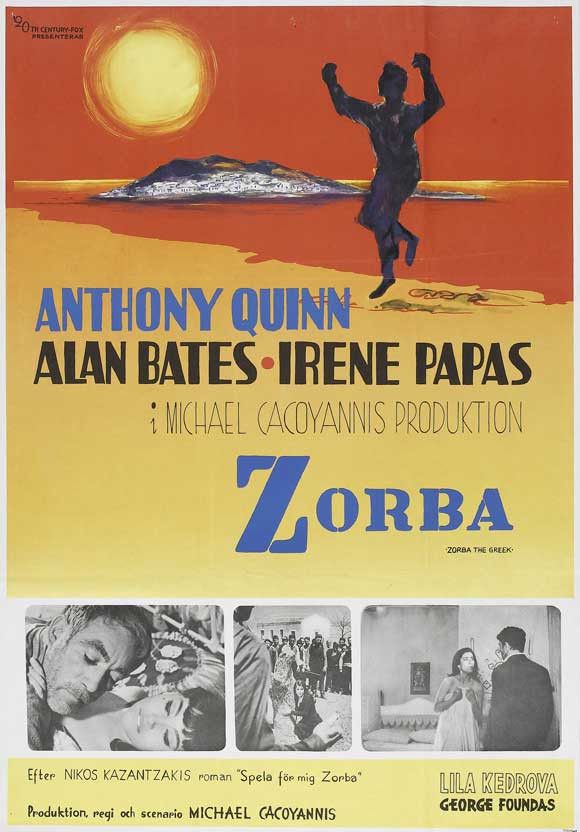

Who will ever forget the first glimpse of Ursula Andress on film in “Dr No” in 1962? She played Honey Ryder to Sean Connery’s debut as James Bond. She was born in Switzerland in 1936. Prior to this, she hade made a few Italian movies and been to Hollywood wehere she was featured on television in Boris Karloff’s “Thriller” series. After “Dr No” she was back in Hollywood again making “Fun In Acapulco” with Elvis Presley and “4 For Texas” with Frank Sinatra, Dean Marin and Anita Ekberg. In “What’s New Pussycat” she starred with three other beaitiful actresses, Paula Prentiss, Romy Schneider and Capucine. She was excellent in the First World War aerial drama “The Blue Max” as the wife of James Mason having an affair with George Peppard. She continues to act on screen.

With her first major film role, actress Ursula Andress assured her place in pop culture history after audiences had their first glimpse of the athletic blonde beauty rising from the Caribbean surf, clad only in a glistening white bikini. After that breakout appearance in “Dr. No” (1962), the first film in the James Bond franchise, the young starlet was quickly placed in lightweight romps like “4 for Texas” (1962) and “Fun in Acapulco” (1962), opposite Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley, respectively. Then-husband John Derek quickly used her to launch his directorial career with B-movie attempts like “Once Before I Die” (1965), although it was her 1965 Playboy pictorial that gained Andress far more attention at the time. Films like the Hammer Studios adventure “She” (1965), the Italian science fiction thriller “The Tenth Victim” (1966) and the WWI aerial melodrama “The Blue Max” (1966), all cashed in on Andress’ reputation as one of the world’s most beautiful women. With her marriage to the controlling Derek long over, the actress appeared in increasingly exploitative features like “Mountain of the Cannibal God” (1978) before meeting the much younger actor Harry Hamlin on the set of “Clash of the Titans” (1981), with whom she had her only child. In the years that followed, she appeared less and less on screen, but occasionally popped up in projects like the miniseries “Peter the Great” (1986) and the art house film “Cremaster 5” (1997), offering fans one more glimpse of the iconic sex symbol.

Born in Berne, Switzerland on March 19, 1936, she was one of six children born to a German diplomat father and a Swiss-German mother. Andress had a restless nature as a child, leaving Switzerland at 17 with a much older Italian actor. Once in Rome, she found work as a bit player in Italian films, mostly comedies which cast her for her abundant physical attributes rather than for any particular acting talent. Andress’ reputation for squiring famous international actors began during the late 1950s; one of her paramours, Marlon Brando, suggested that she try her hand in Hollywood and even arranged for some meetings with studio heads. After signing with Columbia, she headed to America, but found more success in landing boyfriends than movie roles. Among her male admirers during this period was James Dean, who allegedly asked her to accompany him on the ill-fated drive to San Francisco that claimed his life.

Andress found a more persistent suitor in John Derek, a fading matinee idol who was developing a reputation for maintaining strict control of his celebrity girlfriends’ careers and lives. Derek bought out her Columbia contract and kept her off the screen for the next six years. According to Andress, not surprisingly, the marriage was far from a happy one. But by 1962, she had returned to acting, landing the role that would make her an international sex symbol and pop icon – that of Honey Ryder, the first official “Bond Girl” in Terence Young’s film version of Ian Fleming’s “Dr. No.” Unlike many subsequent Bond Girls, Honey was fiercely independent and quite capable of taking care of herself. In one scene, she detailed how she took revenge on a man who raped her by placing a black widow spider in his mosquito netting. And if she became putty in Bond’s hands by the end of the film, men and women alike were captivated by Andress’ combination of lush sexuality, athleticism, and cool Germanic reserve, all of which helped to earn her a 1964 Golden Globe Award for “Dr. No.” Studios also took note of audiences’ reaction to Andress, and her film career was well under way. Amusingly, she also became a literary figure of sorts during this period when Bond author Ian Fleming mentioned her in a scene in his 1963 novel, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

Despite her heavy accent – her dialogue was dubbed by Nikki van der Zyl in “Dr. No” – she found regular work in Hollywood films during the early 1960s. Sadly, the roles were only a few degrees more substantial than those she had landed during her early years in Rome, though she did manage to appear with some of the biggest names in entertainment during the period. She was partnered with another European sex symbol, Anita Ekberg, for the ludicrous Western comedy “4 For Texas” (1963) as love interests to unlikely cowpokes Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, and was romanced by Elvis Presley in the lightweight musical romance “Fun in Acapulco” (1963). She then co-starred with Derek in two of his vanity projects as director: a World War II drama called “Once Before I Die” (1965) and a film noir called “Nightmare in the Sun” (1965) which was more notable for a supporting cast that included Sammy Davis, Jr., Robert Duvall, Aldo Ray, Keenan Wynn and John Marley than the plot, which had good guy Derek mixed up in a blackmail scheme centered around Andress’ married vixen. Not surprisingly, given the limitations placed on beautiful women in Hollywood, Andress garnered more attention for a 1965 layout in Playboy than for any of these features.

By the mid-1960s she was working more in European productions than in Hollywood, and settled into a string of largely ornamental roles that matched the opulence of their sets and locations. For England’s Hammer Films, she played the immortal ruler of a lost civilization in “She” (1965), and in the Woody Allen comedy, “What’s New, Pussycat?” (1965), she was one of several gorgeous starlets who fall madly in love with inveterate cad, Peter O’Toole. In the Italian science fiction thriller “The Tenth Victim” (1966), Andress was a hired killer who dispatched her victims with a brassiere that fired bullets, while in “The Blue Max” (1966), she was the sexually insatiable wife of a top general in Kaiser Wilhelm’s air force during World War I.

Andress’ marriage to Derek was unraveling during this period, and she eventually divorced him after launching into a passionate affair with French actor Jean-Paul Belmondo, her co-star in “Les Tribulations d’un Chinois en Chine” (“Chinese Adventures in China”) (1966), a lighthearted period comedy. The relationship was a tumultuous one, with both sides wreaking emotional and occasional physical havoc on each other or themselves. Despite the turmoil, she remained very active in European films, most notably the troubled and overblown Bond parody “Casino Royale” (1967). Other notable projects during this period were the caper drama “Perfect Friday” (1970) and “Red Sun” (1971), a curious mix of spaghetti Western and samurai film that pitted gunfighter Charles Bronson against Toshiro Mifune.

However, by the mid-1970s, Andress was mired in a string of low-budget and often low-rent projects that required little more from her than onscreen nudity. The most appalling of these were “The Sensuous Nurse” (1975), a rank Italian sexploitation comedy with Andress as the title character who has been hired by greedy relatives of a dying man to help facilitate his demise, and “Mountain of the Cannibal God” (1978), an Italian horror-adventure film that balances scenes of a nude Andress being painted all over by primitive tribesmen with footage of real animal slaughter. To perhaps balance the lack of quality in her projects, Andress was romantically involved with numerous leading men during the freewheeling 1970s, including Warren Beatty, Ryan O’Neal and Italian actor Fabio Testi. However, Andress frequently cited Derek as the one man to whom she felt the most connection.

In 1981, Andress was shrewdly cast as Aphrodite, Greek goddess of love, in Ray Harryhausen’s special effects spectacular “Clash of the Titans.” She soon fell for the film’s leading man, then newcomer Harry Hamlin who was nearly 20 years her junior. She gave birth to their son, Dmitri, in 1980, but her relationship with Hamlin came to an end just two years later. Andress kept busy during the Eighties in international productions, as well as American television, where older but still glamorous actresses were in vogue on primetime soap operas. She did a one-year stint on “Falcon Crest” (CBS, 1981-1990) as an exotic foreigner who assists David Selby in retrieving Dana Sparks from a white slave ring, and later turned up in the miniseries “Peter the Great” (1986) opposite Maximillian Schell. One of her last film roles to date was a turn as a fantasy queen in the experimental film “Cremaster 5” (2005) by arthouse darling Matthew Barney. As Andress approached her seventh decade, her screen image retained its sensual power, and she was showered with praise and awards by several international publications. Britain’s Empire magazine named her one of the “100 Sexiest Stars in Film History” in 1995, while Channel 4 placed her arrival on the beach in “Dr. No” at the top of their “100 Greatest Sexy Moments” poll in 2003.

TCM Overview can be accessed online here.