New York Times” obituary from 1992:

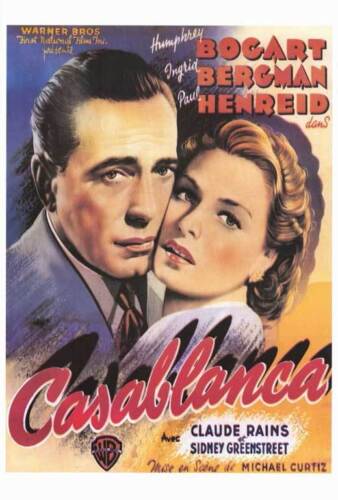

Paul Henreid, the suave leading man who won screen immortality as the noble, Nazi-battling Resistance leader Victor Lazlo in the 1942 film classic “Casablanca,” died on Sunday at Santa Monica Hospital in Santa Monica, Calif. He was 84 years old and lived in Pacific Palisades, Calif.

He died of pneumonia after a stroke, said Henry Alter, Mr. Henreid’s former secretary. The family did not want to announce the death until Mr. Henreid was buried yesterday in Santa Monica, Mr. Alter said yesterday.

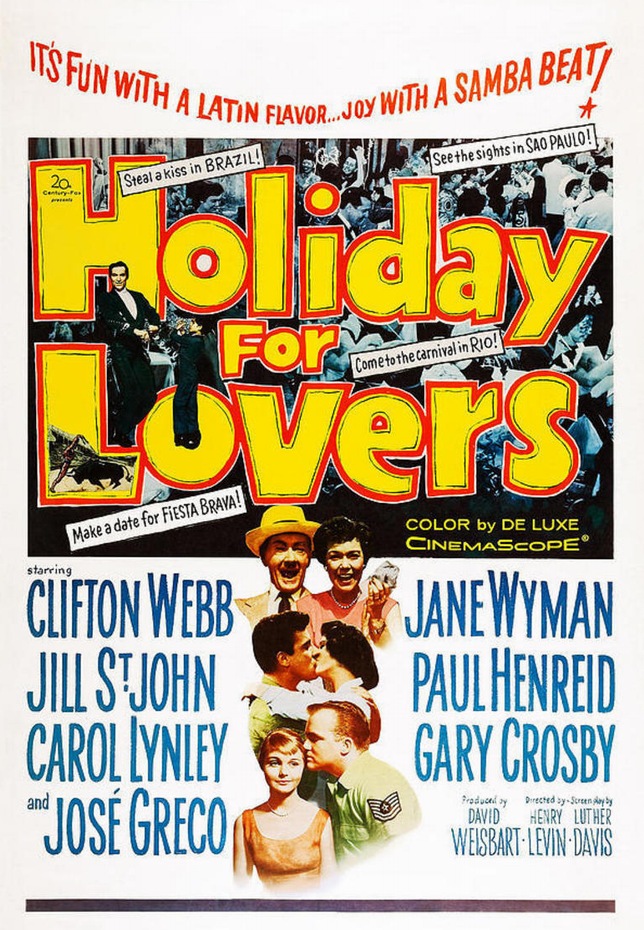

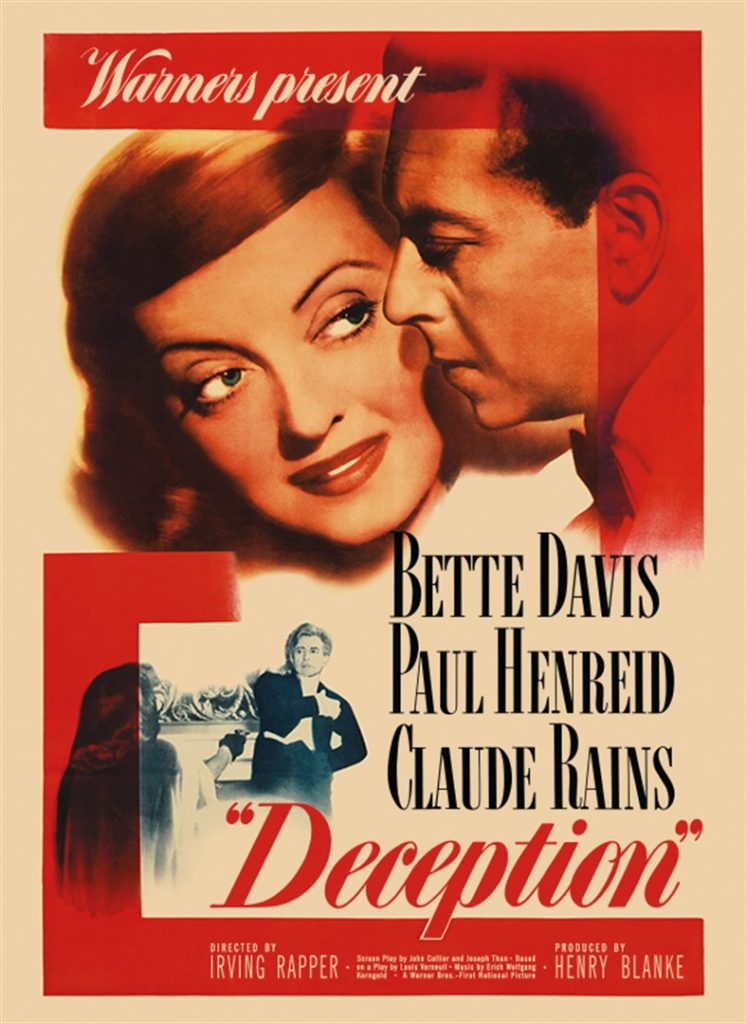

The actor died only days before the first major theatrical re-release of “Casablanca” in more than 35 years, scheduled for April 10 as part of the film’s 50th-anniversary celebrations. Despite that movie’s classic status, however, Mr. Henreid may be best remembered for a scene in “Now Voyager” (1942) in which he lit two cigarettes at once as he comforted Bette Davis. Mr. Henreid later said that the director, Irving Rapper, didn’t like that bit of business and went along with it only reluctantly.

Mr. Henreid once estimated that he had acted in or directed more than 300 films and television dramas. In his heyday as a leading man, the 6-foot-3 actor seemed to represent the prototype of the Continental lover to American film audiences: aristocratic, elegant and gallant. A Charmed Childhood

Mr. Henreid was born on Jan. 10, 1908, in Trieste, then a part of Austria. His full name was Paul George Julius von Hernreid. He was the son of Baron Carl Alphons, a prominent Viennese banker, and Maria-Luise von Hernreid.

In his 1984 autobiography, “Ladies Man,” written with Julius Fast, he described what he called a charmed childhood among the aristocrats of pre-World War I Vienna. But by 1927, when Mr. Henreid graduated from the exclusive Maria Theresianische Academie, little of the family fortune remained.

He wanted to be an actor but, bowing to his family’s wishes, worked with a publishing house in Vienna for four years while studying acting at night. During an acting-school performance, he was discovered by Otto Preminger, then Max Reinhardt’s managing director, and became a leading player in Reinhardt’s theater. Like the fictional Victor Lazlo, Mr. Henreid was a staunch anti-Nazi during his years in Europe. A Series of German Roles

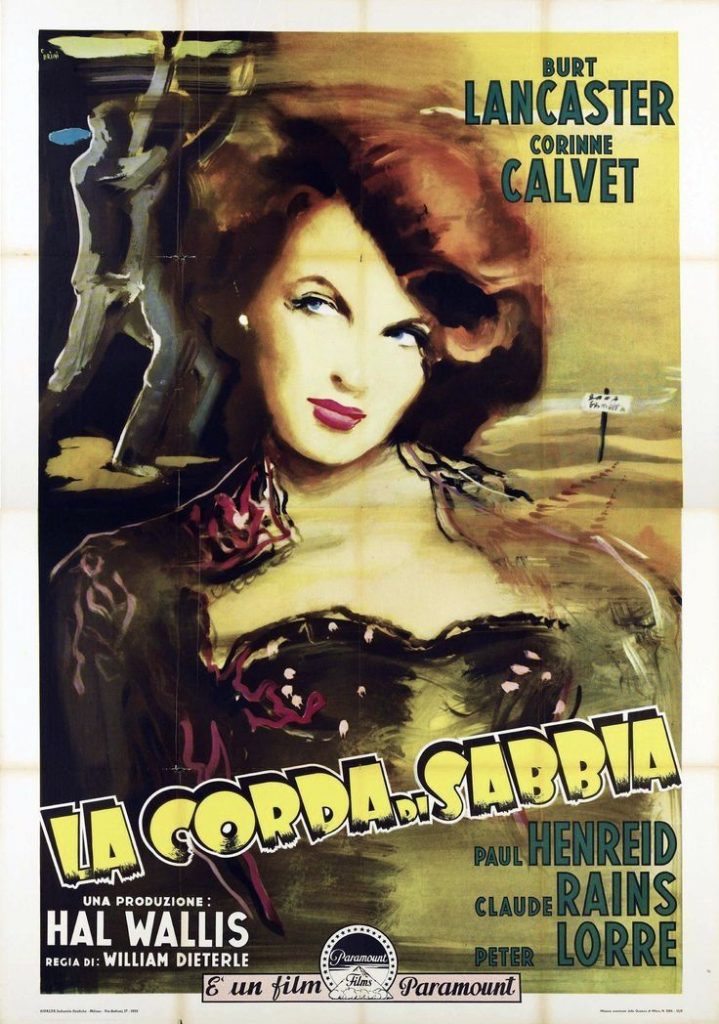

In 1937 he won wider recognition by playing Prince Albert in “Victoria Regina” on the London stage. Despite his personal sentiments, he was fated for a time to play a series of German roles. In one of his first films, “Goodbye, Mr. Chips” (1939), he played a young German teacher; he was a Nazi officer in “Madman of Europe” (1940) and a Gestapo agent in Carol Reed’s “Night Train” (1940).

Mr. Henreid’s first big American success was in another such role, that of the bombastic German consul in the Guild Theater production of “Flight to the West.” The play opened in New York on Dec. 30, 1940, and helped get him his first Hollywood contract, with RKO Radio Pictures in 1941. Later that year, Mr. Henreid became a United States citizen, but he resisted the studio’s attempt to change his name to Herndon or Henrie.

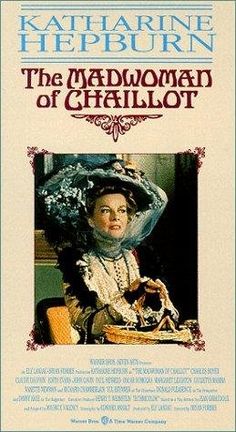

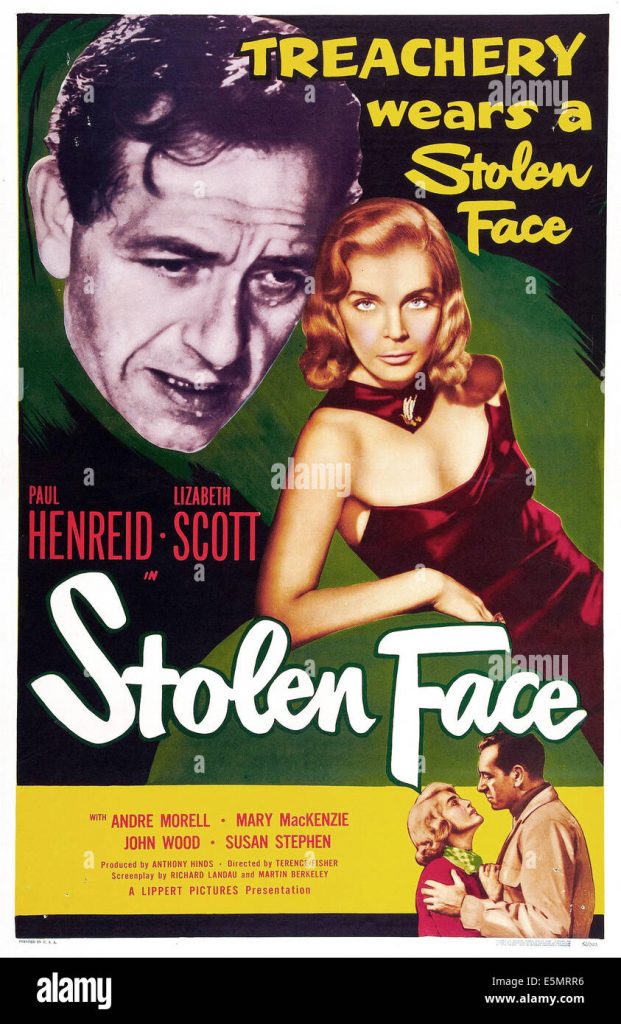

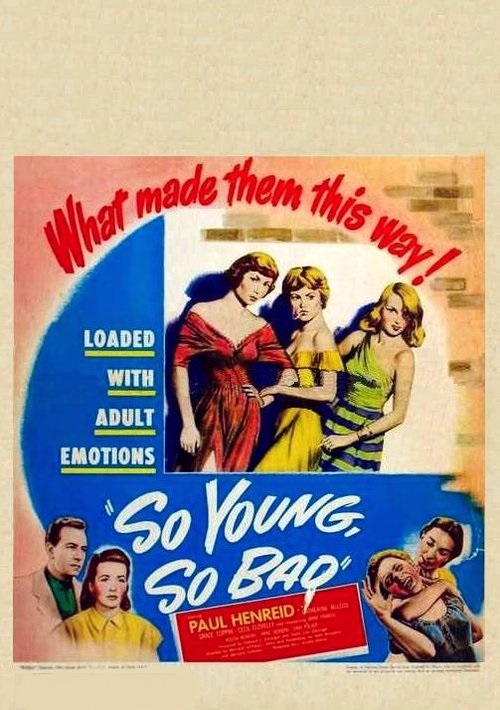

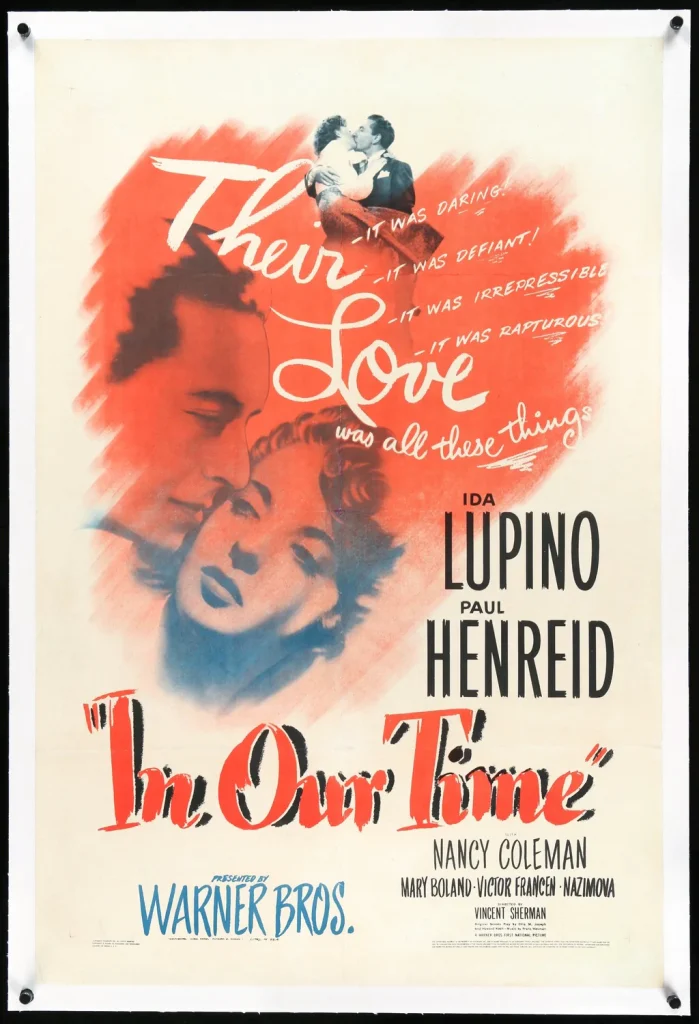

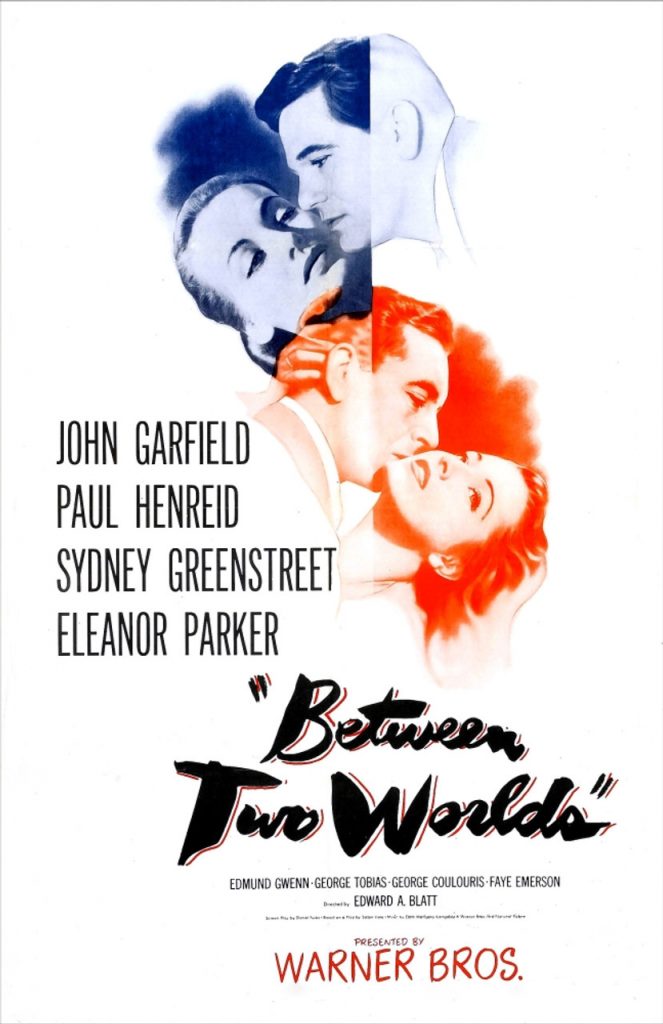

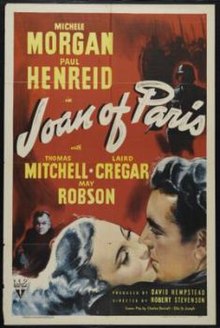

He broke free of the Germanic stereotype in his first Hollywood film, “Joan of Paris” (1942), in which he played a heroic Free French R.A.F. pilot, and went on to glory as the underground leader in “Casablanca.” He then played an Irish patriot in “Devotion” (1943) and a Polish count in “In Our Time” (1944). A Survivor of the Blacklist

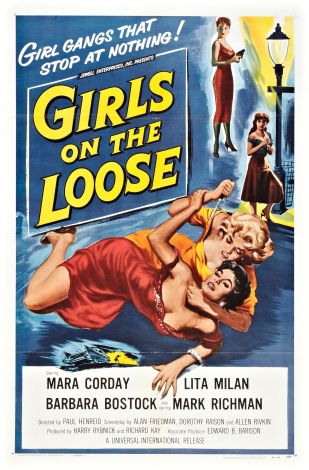

In his autobiography, Mr. Henreid said his Hollywood film career was all but destroyed by the anti-Communist blacklist. Mr. Henreid was one of a group of Hollywood stars who went to Washington to protest the excesses of the House Committee on Un-American Activities.In the 1950’s, Mr. Henreid found a second career as a director and producer. He directed more than 80 episodes of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” for television; Hitchcock hired him in 1955 despite the blacklist.

Mr. Henreid also acted in numerous television films and toured nationally in the play “Don Juan in Hell” in 1972 and 1973.He is survived by his wife, Lisl, and two daughters, Mimi Duncan and Monica Henreid

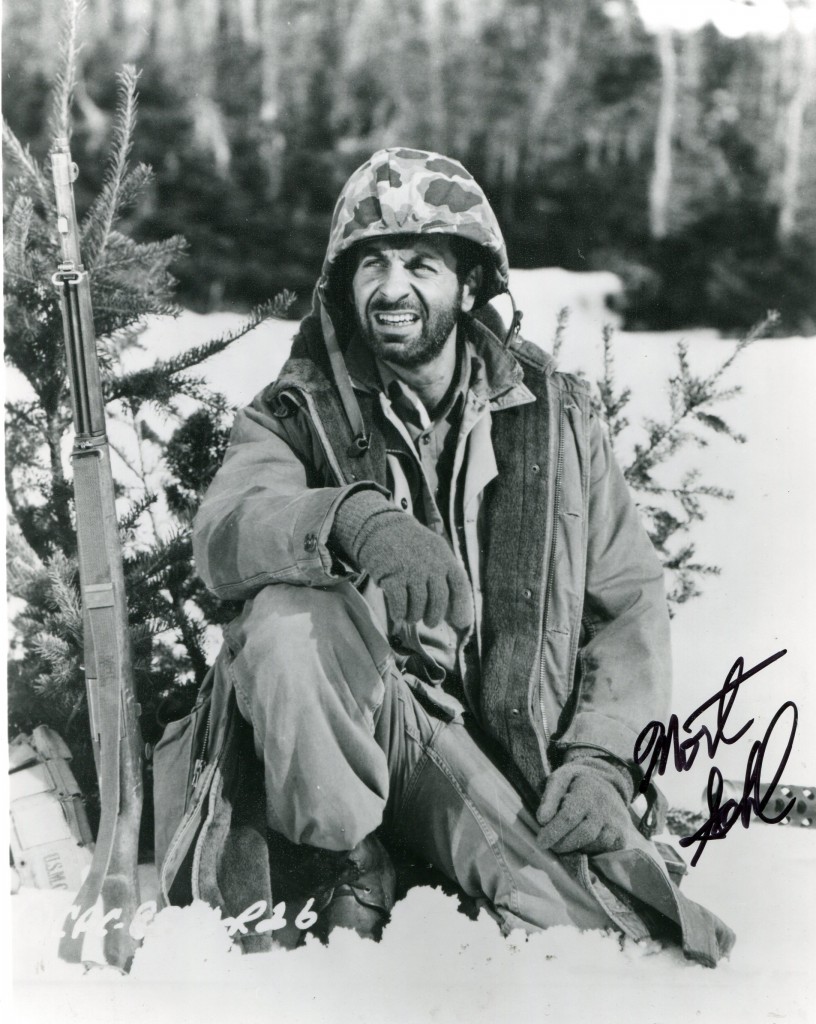

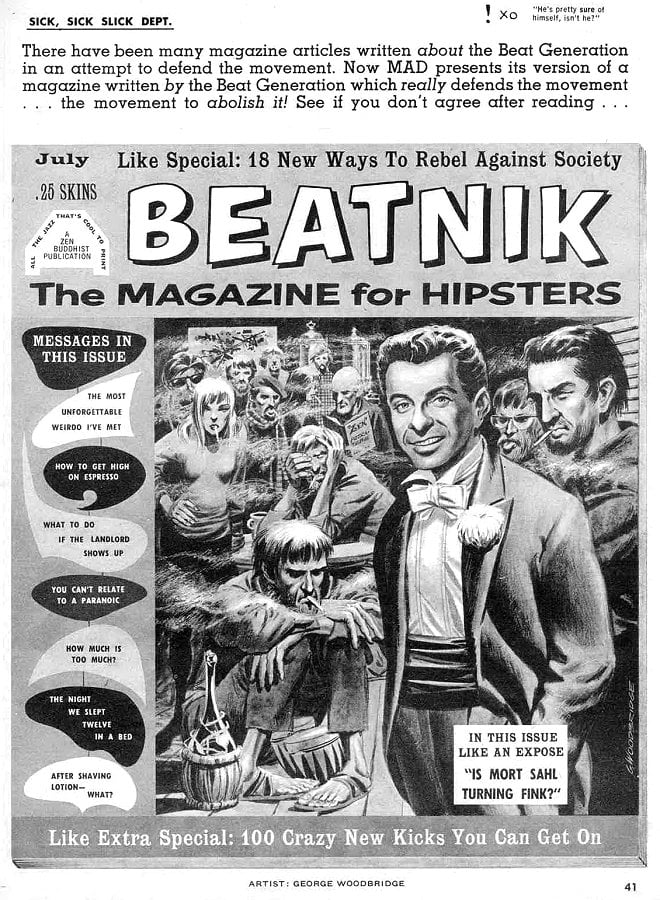

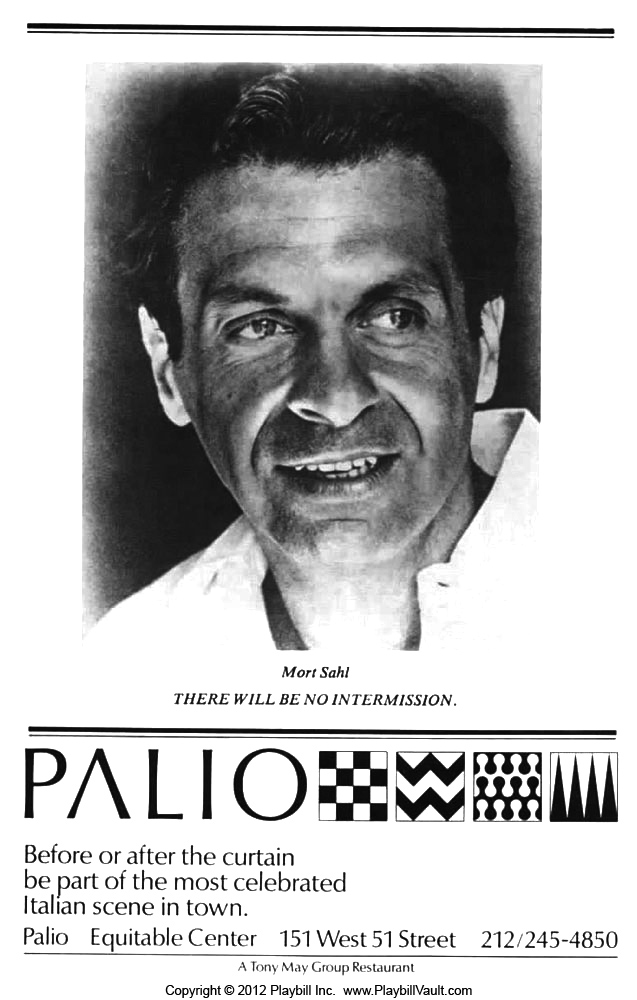

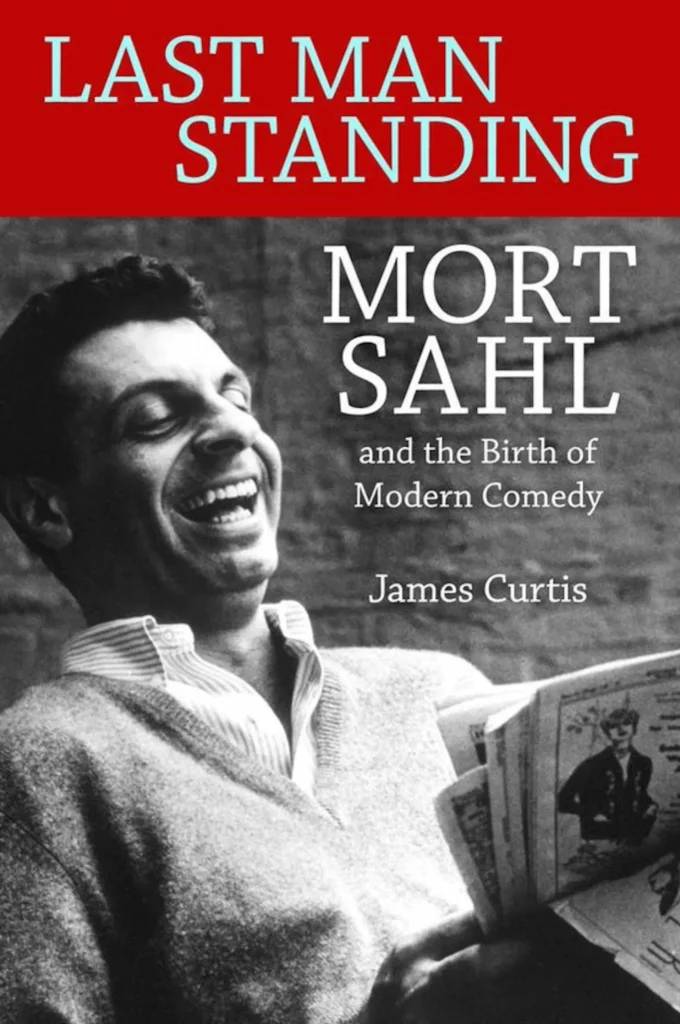

The comedian and satirist Mort Sahl, who has died aged 94, was a combination of Lenny Bruce and Bob Hope – with a little Will Rogers thrown in. Like Bruce, Sahl was a product of the 1950s. Like Hope, he was as much a reporter and commentator on the events of the day as a morning newspaper. And like Rogers, who took the US by the heartstrings during the days of the Great Depression, he would walk on stage with one of those papers in his hand and proceed to take a famous figure to task.

Rogers just made jokes about the people in the news, but Sahl specialised in demolishing them. Different from Hope, who employed an army of ghostwriters, Sahl wrote all his own material – and not just for himself; for a while he was President John F Kennedy’s principal joke writer. To much surprise, he later became a close friend of Ronald Reagan.

Unlike Bruce, who used to say that Sahl was his inspiration, he did not shock with obscenities and the drug culture seemed to be foreign to him. Nevertheless, he had the effect of a heat-seeking missile on his targets. When American politicians were in trouble, they had to take cover whenever Sahl appeared on stage or on a television talk show. Kennedy said he liked Sahl because he admired a man who was “in relentless pursuit of everybody”.

Born in Montreal, he was the son of Harry Sahl, a Jewish-American court reporter who had gone to Canada to write plays and go into business. When this failed, he took his wife, Dorothy, and son, Morton, back to the US and became an administrator for the FBI. The younger Sahl would later become the subject of a considerable FBI file about his suspected communist leanings. Nothing stuck, however, and his political affiliations were never clear.

At school in Los Angeles, he was a member of the officer cadet corps. He was drafted into the US air force soon after the second world war and stationed in Alaska, where he worked on the base newspaper. He then went to the University of Southern California to take a degree in city management. Before long, his only connection with that worthy subject would be lambasting it from the stage of a smoke-filled club or a small theatre – although usually his targets were larger.

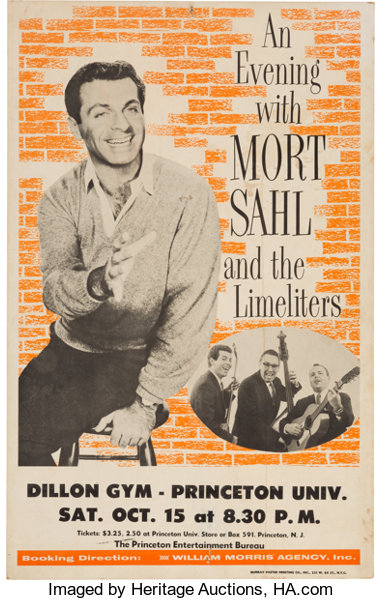

He almost starved trying to sell his writing before he arrived at the hungry i nightclub in San Francisco in the early 50s, but by the end of the decade and in the early 60s, he was the favourite nightclub entertainer in the more sophisticated parts of New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. What many of the well-heeled and well-known patrons liked about him was that he had no more respect for the leftwing than for the establishment on the right.

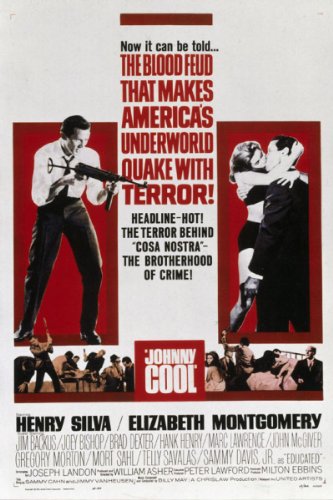

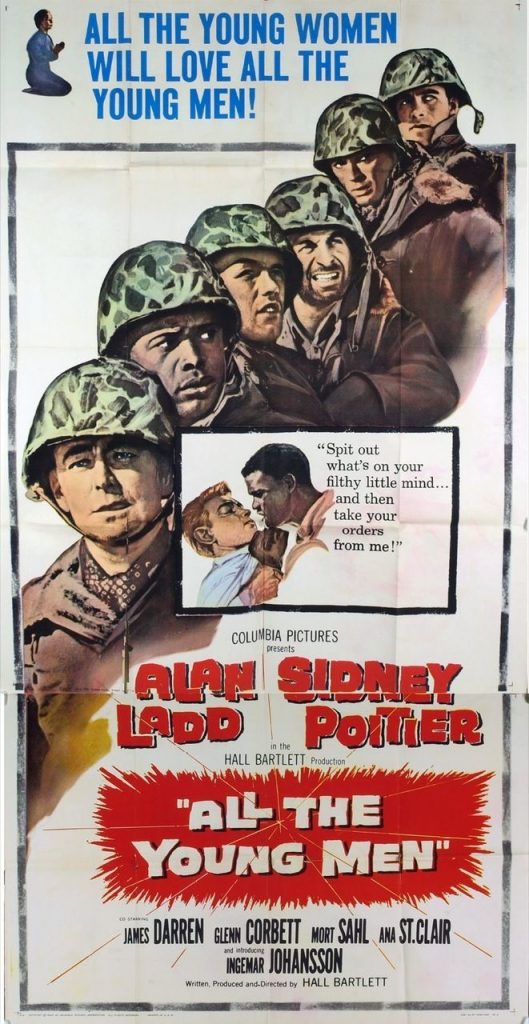

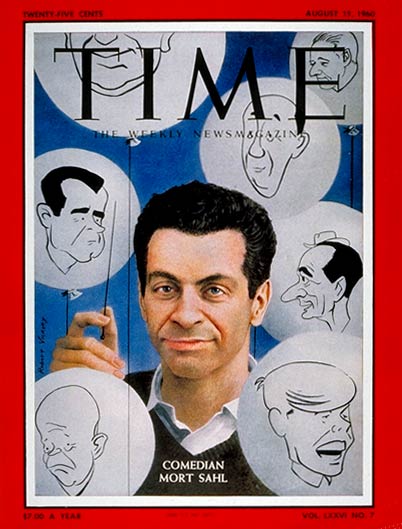

He was one of the first satirical comedians to make LP records and sell them, the first being At Sunset, recorded in 1955. He became such an influential figure that Time magazine devoted one of its celebrated cover features to him, describing him as “Will Rogers with fangs”. Sahl also wrote screenplays and occasionally appeared in films himself, including Johnny Cool (1963), Inside the Third Reich (1982) and Nothing Lasts Forever (1984).

For a while in the 60s, his fame and appeal began to wane, but Sahl regarded it as his duty to continue to attack whatever he believed needed attacking. The assassination of Kennedy in 1963 was a landmark: he regarded the president’s killing as he would the death of a close relative. When the Warren commission declared that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone, Sahl took it as a personal affront and campaigned to have the findings reversed.

The Vietnam war was perfect grist for the mill of his talent; people began to want to hear what he said about it, and he guested again on the top talk shows. But his stage work faded until the late 80s – when, for the first time, he had a four-week run at a Broadway theatre. He came out on to a bare stage, as he always did, in a pair of slacks and a V-neck sweater. But there was the inevitable folded newspaper and the comment on the world around him.

“Washington couldn’t tell a lie,” he said, “Nixon couldn’t tell the truth and Reagan couldn’t tell the difference.” Although he was a frequent guest at the White House during the Reagan years, the president remained a target.

He would skewer politicians of all parties, latterly including Barack Obama and Donald Trump. Asked what his principal philosophy was, he would say “I am allergic to majorities” and he was known for the stage catchphrase: “Are there any groups I haven’t offended?” In 2004 he described himself as “a disturber”.

When he talked about retirement, he would say: “I’d be glad to relinquish the reins and go on and do something useful … but I can’t seem to clean up the town.” He carried on performing once a week until prevented by the pandemic.

The New York Post critic Clive Barnes once wrote of Sahl: “The real joy of the man, and his show, is the quickness of his mind and his wonderful sense of nonsense. Forget that the man is clever. Merely think of him as the funniest guy in town.”

Sahl was married and divorced four times. His son, Mort Jr, from his second marriage, to China Lee, died in 1996.

Morton Lyon Sahl, comedian, born 11 May 1927; died 26 October 2021