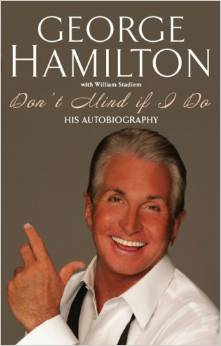

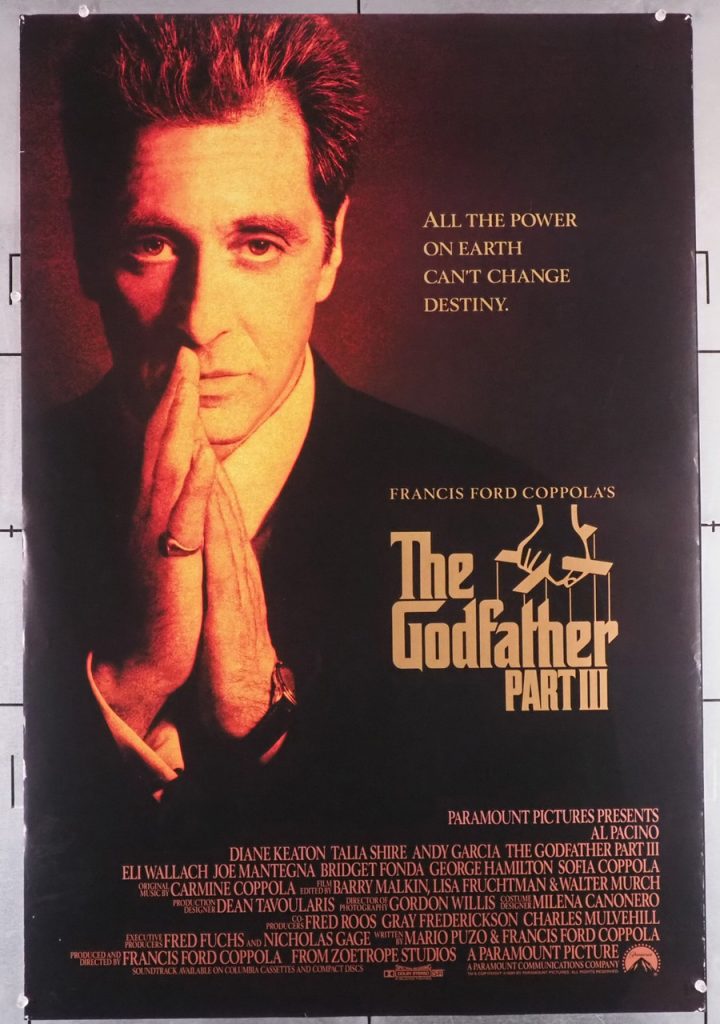

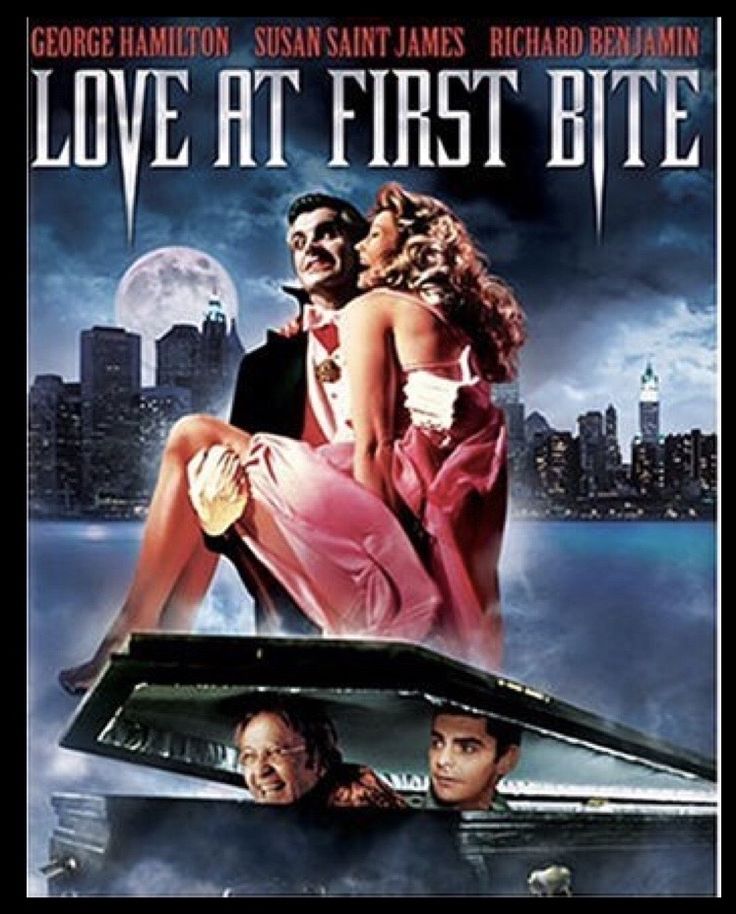

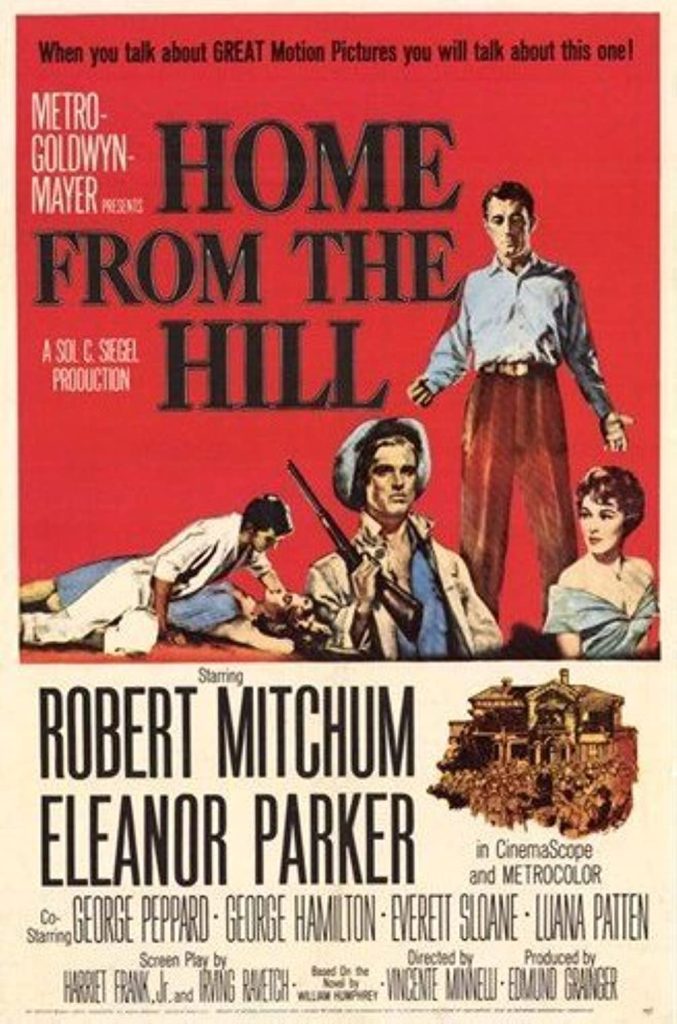

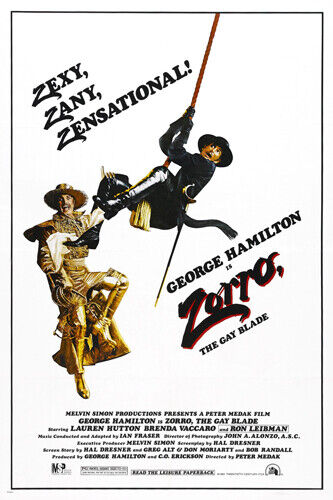

George Hamilton was born in Memphis in 1939. “Whwrw the Boys Are” released in 1960 ith Dolores Hart and Connie Francis was his first film lead role to achieve major recognition. He was also noticed in “Home from the Hill” a lurid melodrama where he was the weakish son of Robert Mitchum and Eleanor Parker. In 1979 he had an un expected major hit with “Love at First Bite” a spoof of the Dracula films. He followed this movie with another succesful film “Zorro the Gay Blade”. However he did not sustain his career momentum as a leading man and began to take television roles. In 1990 he was featured in “The Godfather Part 3”. He has recently published his autobiography “I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here” which won praise for it’s self-deprecating humour. A “MailOnline” interview with George Hamilton can be accessed here.

Gary Brumburgh’s entry:

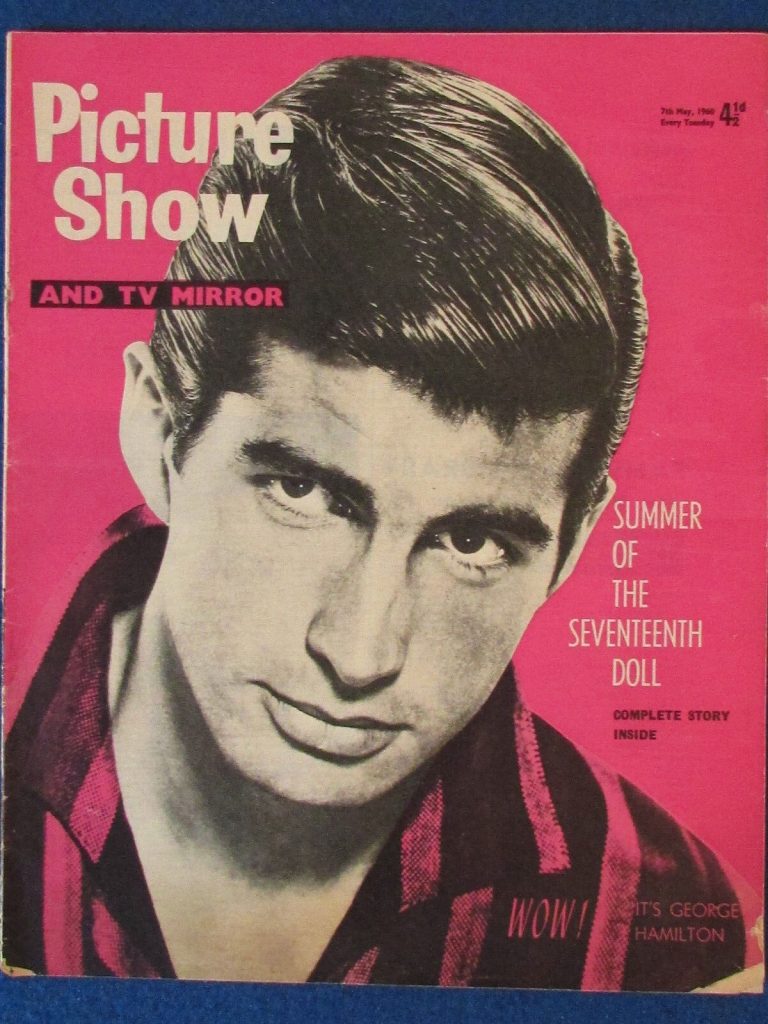

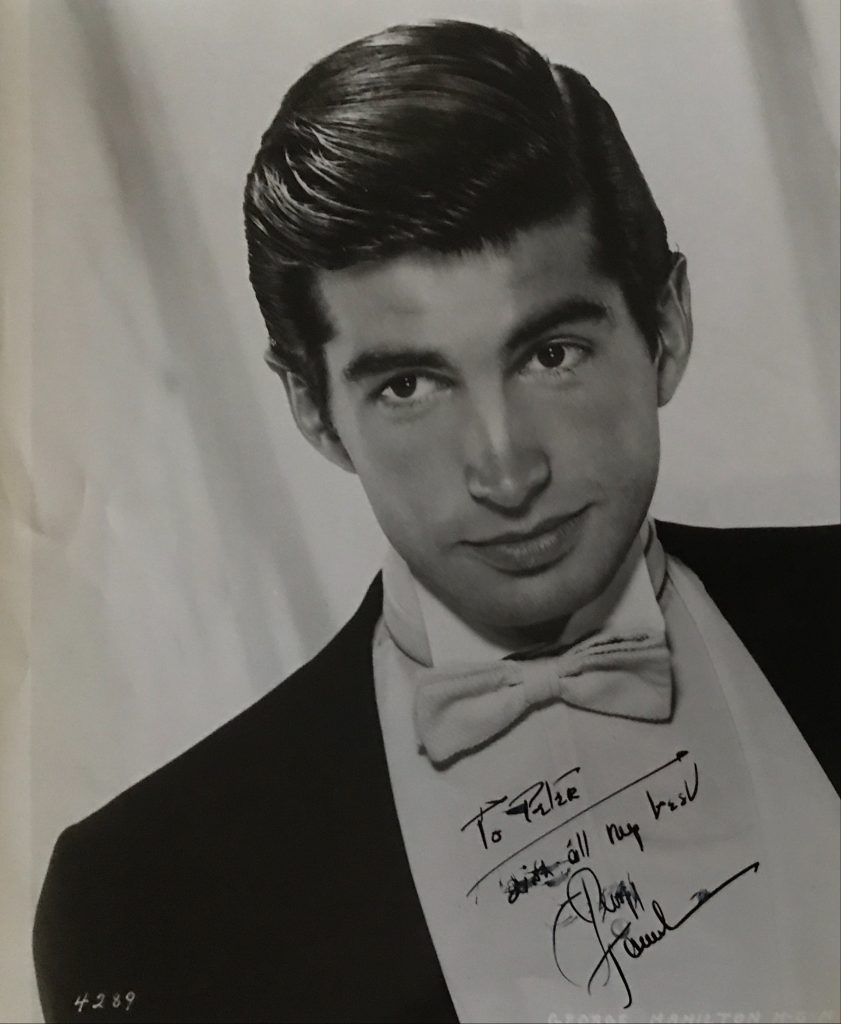

Noted these days for his dashing, sporting, jet-setter image and perpetually bronzed skin tones in commercials, film spoofs and reality shows, George Hamilton was, at the onset, a serious contender for dramatic film stardom. Born George Stevens Hamilton IV in Memphis, TN, on August 12, 1939, the son of gregarious Southern belle beauty Ann Potter Hamilton Hunt Spaulding, whose second husband (of four) was George Stevens “Spike” Hamilton, a touring bandleader. Moving extensively as a youth due to his father’s work (Arkansas, Massachusetts, New York, California), young George got a taste of acting in plays while attending Palm Beach High School. With his exceedingly handsome looks and attractive personality, he took a bold chance and moved to Los Angeles in the late 1950s.

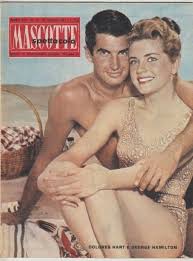

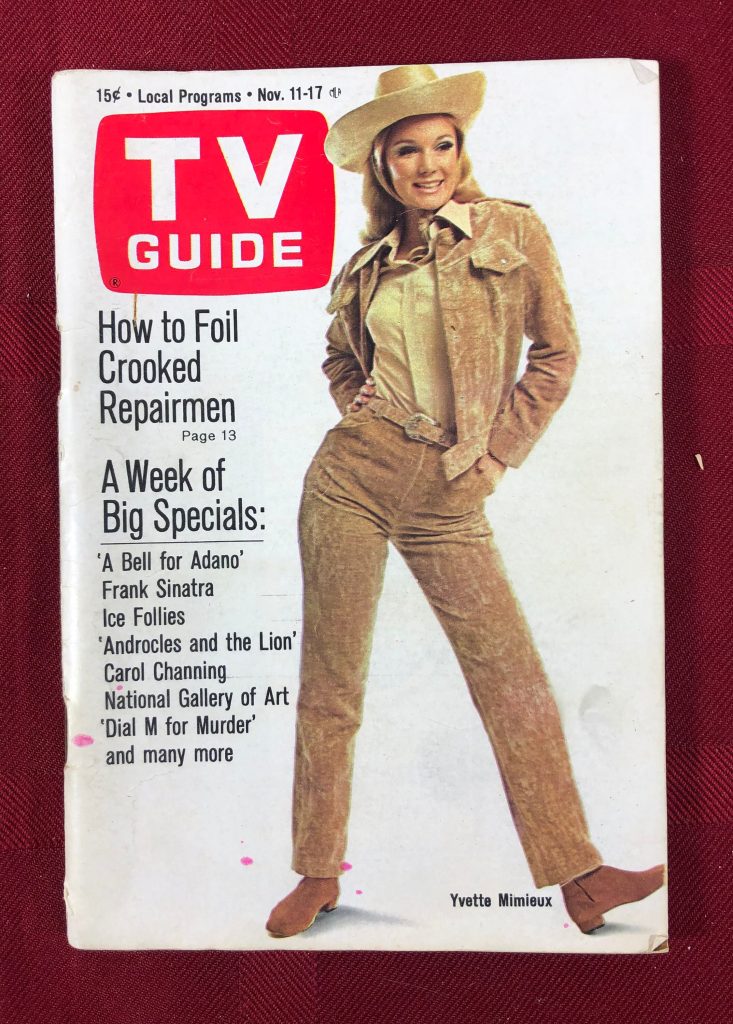

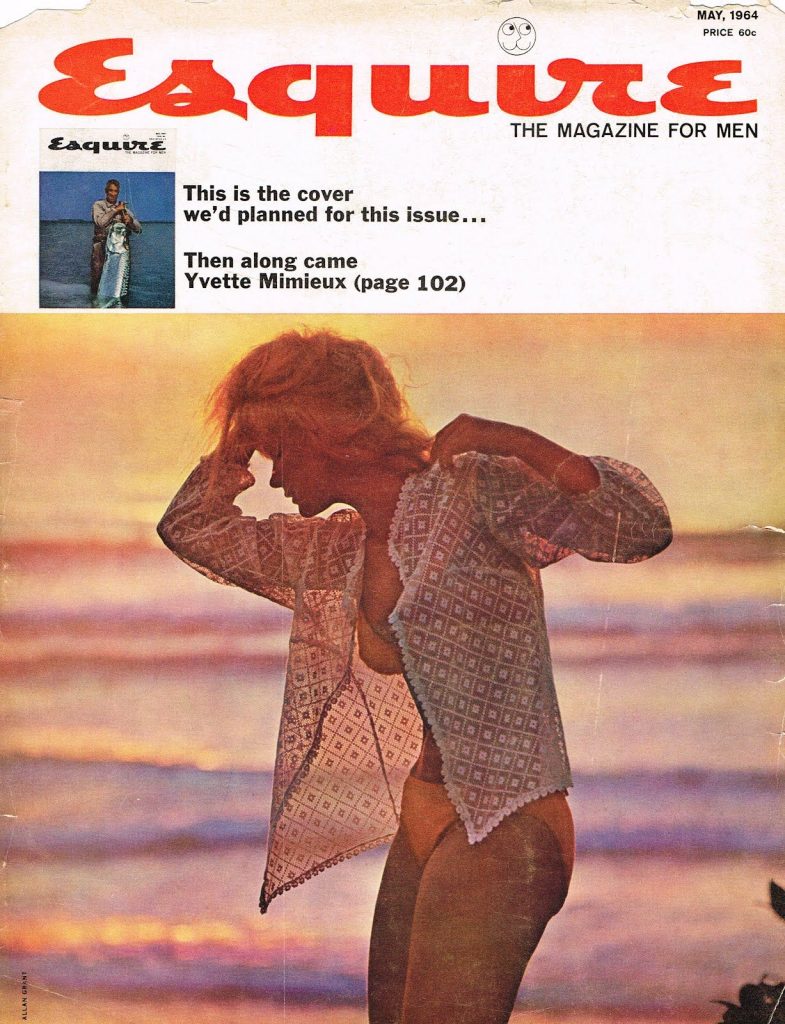

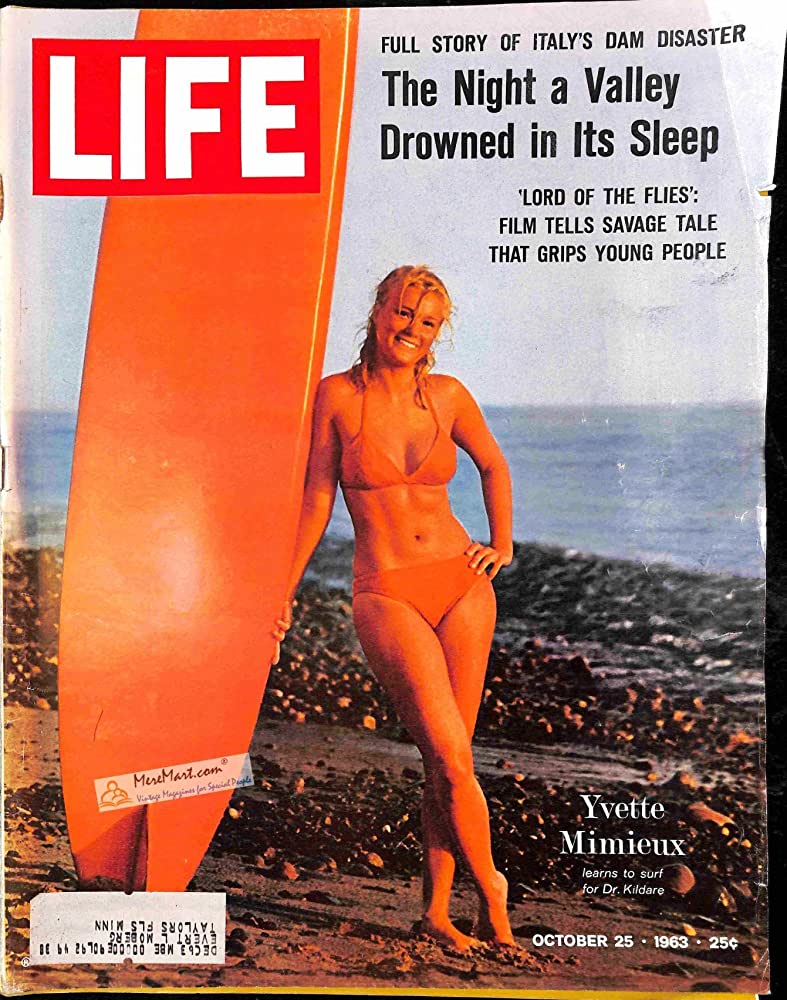

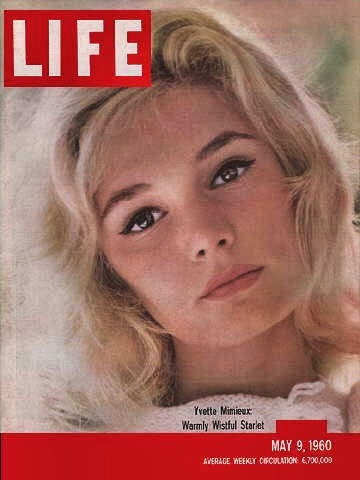

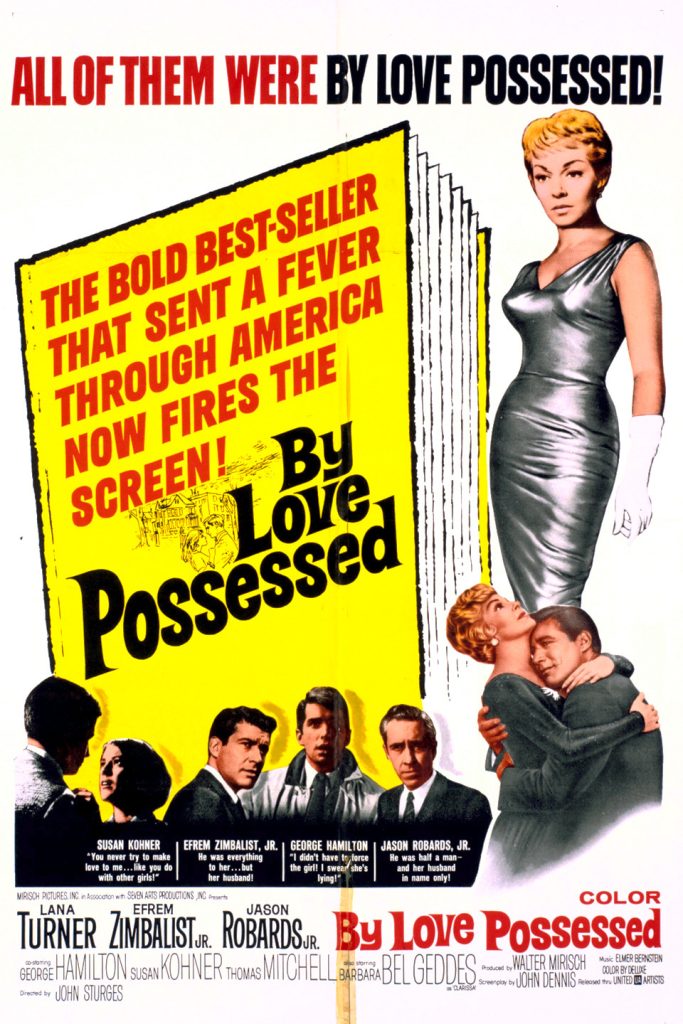

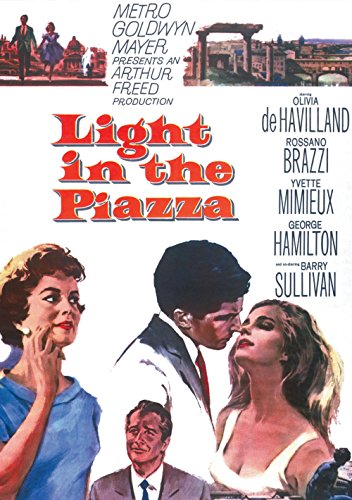

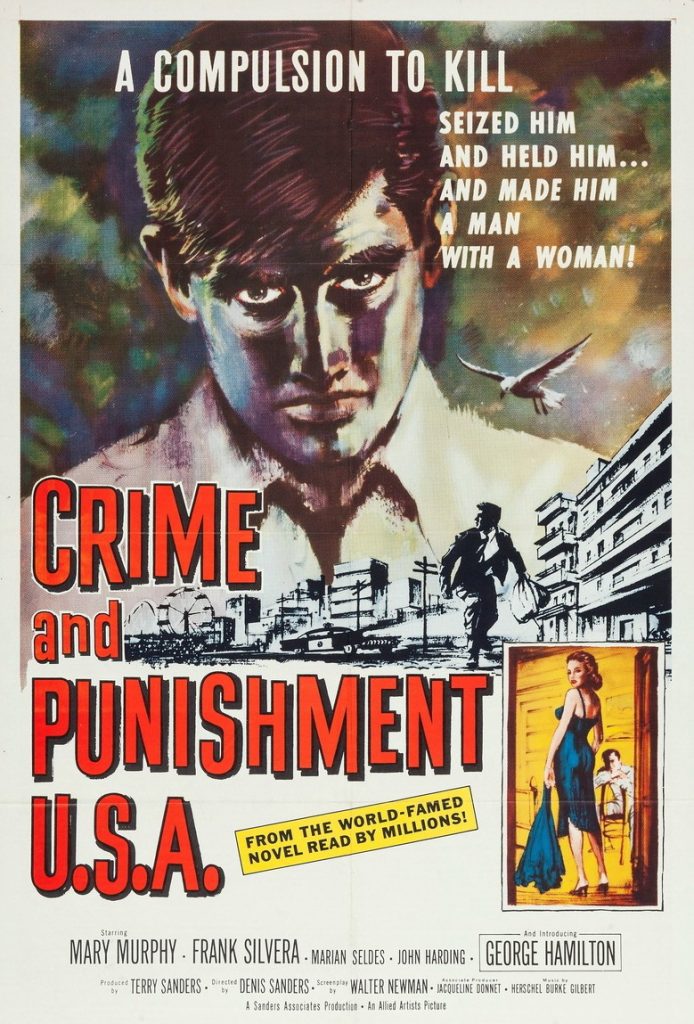

MGM (towards the end of the contract system) saw in George a budding talent with photogenic appeal. It wasted no time putting him in films following some guest appearances on TV. His first film, a lead in Crime & Punishment, USA (1959), was an offbeat, updated adaptation of the Fyodor Dostoevsky novel. While the film was not overwhelmingly successful, George’s heartthrob appeal was obvious. He was awarded a Golden Globe for “Most Promising Newcomer” as well as being nominated for “Best Foreign Actor” by the British Film Academy (BAFTA). This in turn led to an enviable series of film showcases, including the memorable Southern drama Home from the Hill (1960), which starred Robert Mitchum and Eleanor Parker and featured another handsome, up-and-coming George (George Peppard); Angel Baby (1961), in which he played an impressionable lad who meets up with evangelist Mercedes McCambridge; and Light in the Piazza (1962) (another BAFTA nomination), in which he portrays an Italian playboy who falls madly for American tourist Yvette Mimieux to the ever-growing concern of her mother Olivia de Havilland. Along with the good, however, came the bad and the inane, which included the dreary sudsers All the Fine Young Cannibals (1960) and By Love Possessed (1961) and the youthful spring-break romps Where the Boys Are (1960), which had Connie Francis warbling the title tune while slick-as-car-seat-leather George pursued coed Dolores Hart, and Looking for Love (1964), which was more of the same.

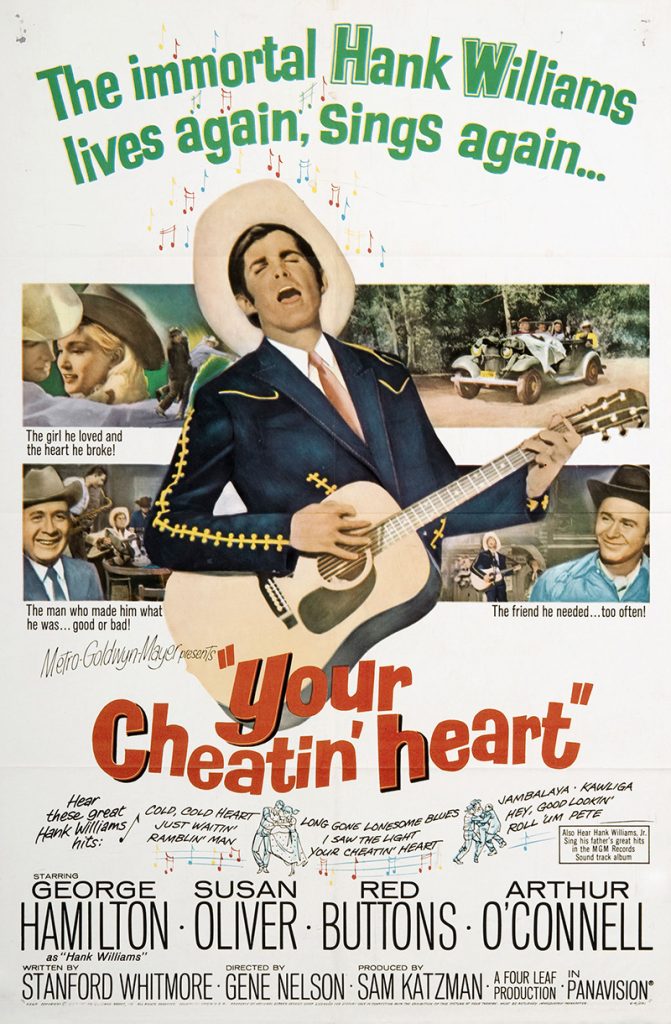

Not yet undone by this mixed message of serious actor and glossy pin-up, George went on to show some real acting muscle in the offbeat casting of a number of biopics — asMoss Hart in Act One (1963), an overly fictionalized and sanitized account of the late playwright (the real Moss should have looked so good!), as ill-fated country star Hank Williams in Your Cheatin’ Heart (1964), and as the famed daredevil Evel Knievel (1971).

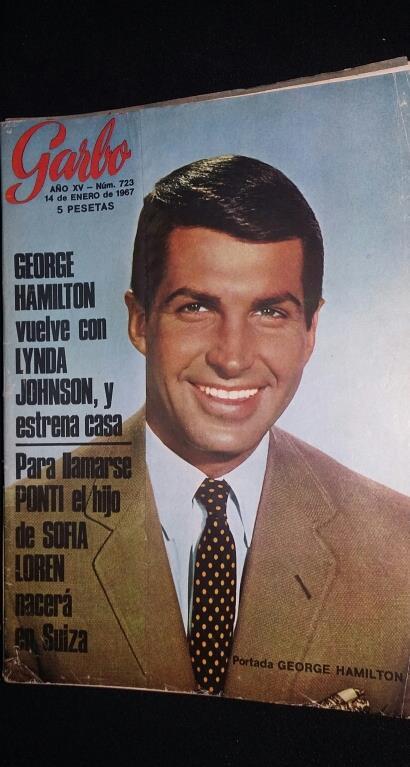

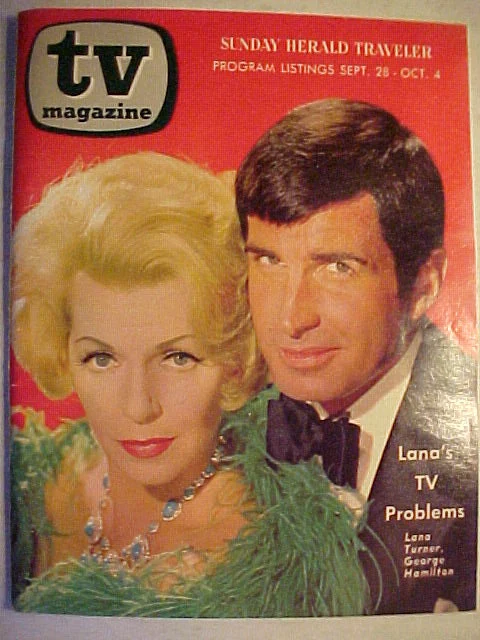

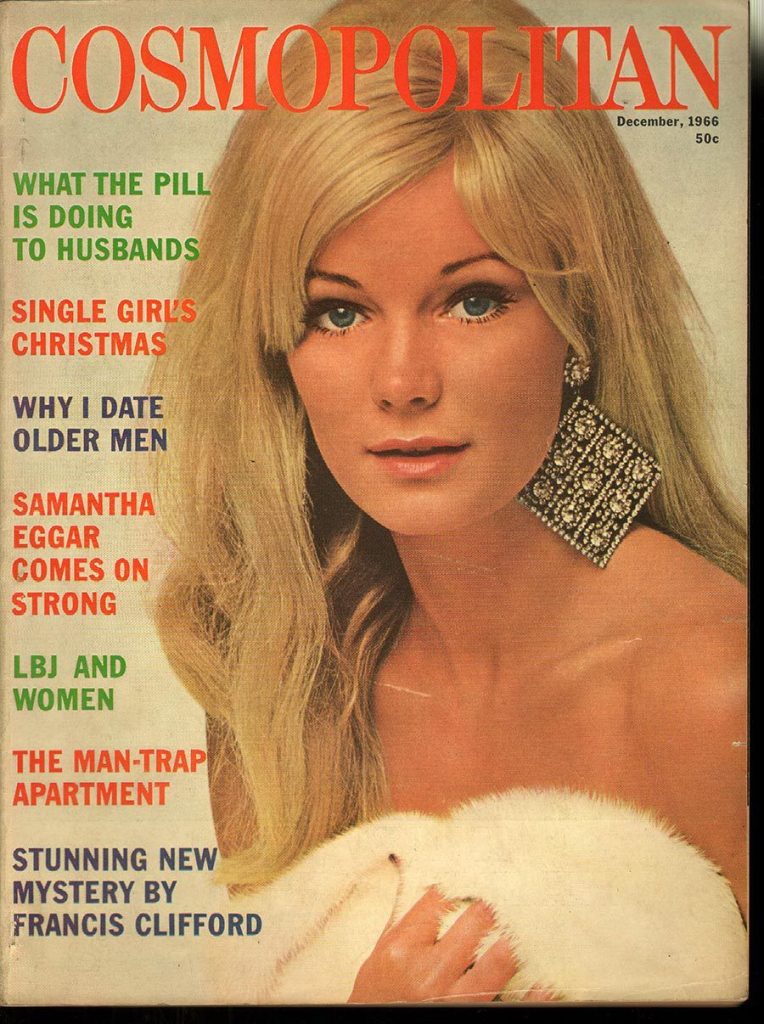

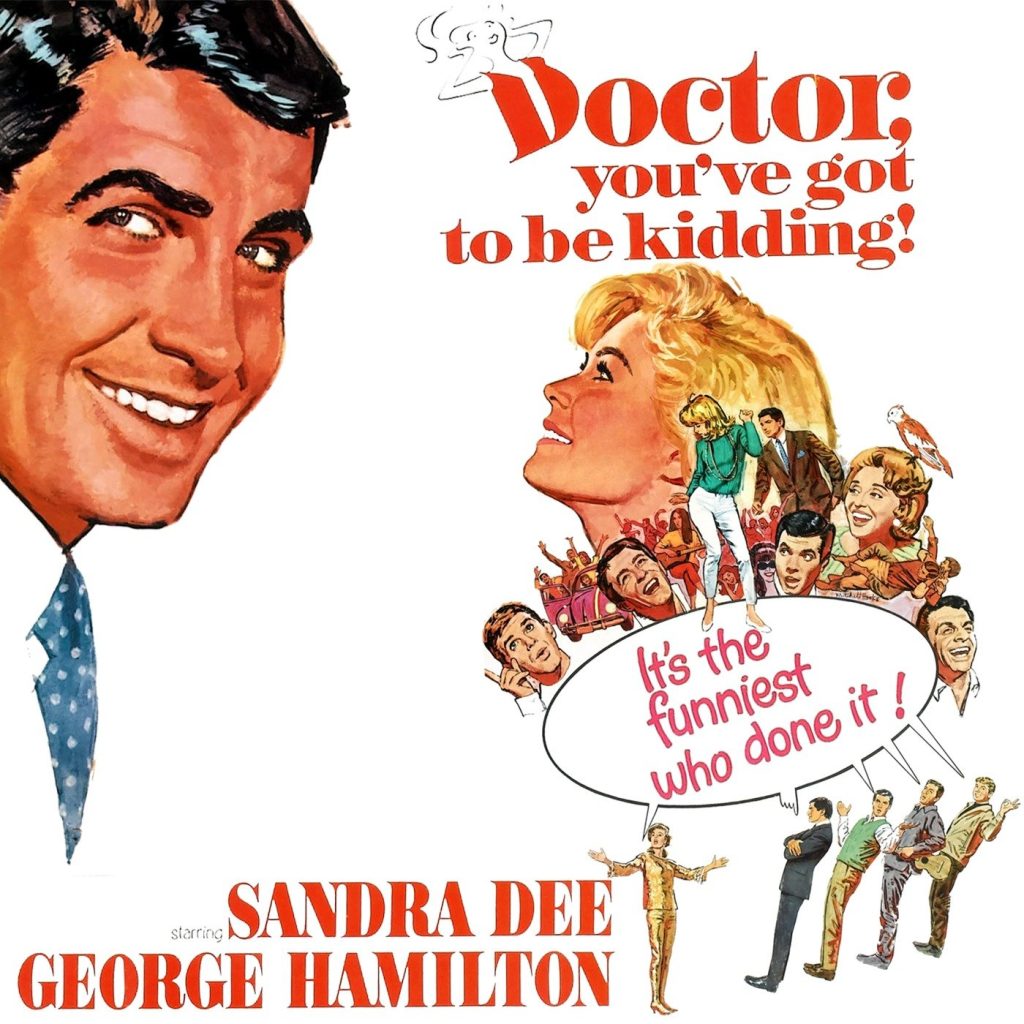

The rest of the ’60s and ’70s, however, rested on his fun-loving, idle-rich charm that bore a close resemblance to his off-camera image in the society pages. As the 1960s began to unfold, he started making headlines more as a handsome escort to the rich, the powerful and the beautiful than as an acclaimed actor — none more so than his 1966 squiring of President Lyndon Johnson‘s daughter Lynda Bird Johnson. He was also once engaged to actress Susan Kohner, a former co-star. Below-average films such as Doctor, You’ve Got to Be Kidding! (1967), A Time for Killing (1967) and The Power (1968) effectively ended his initially strong ascent to film stardom.

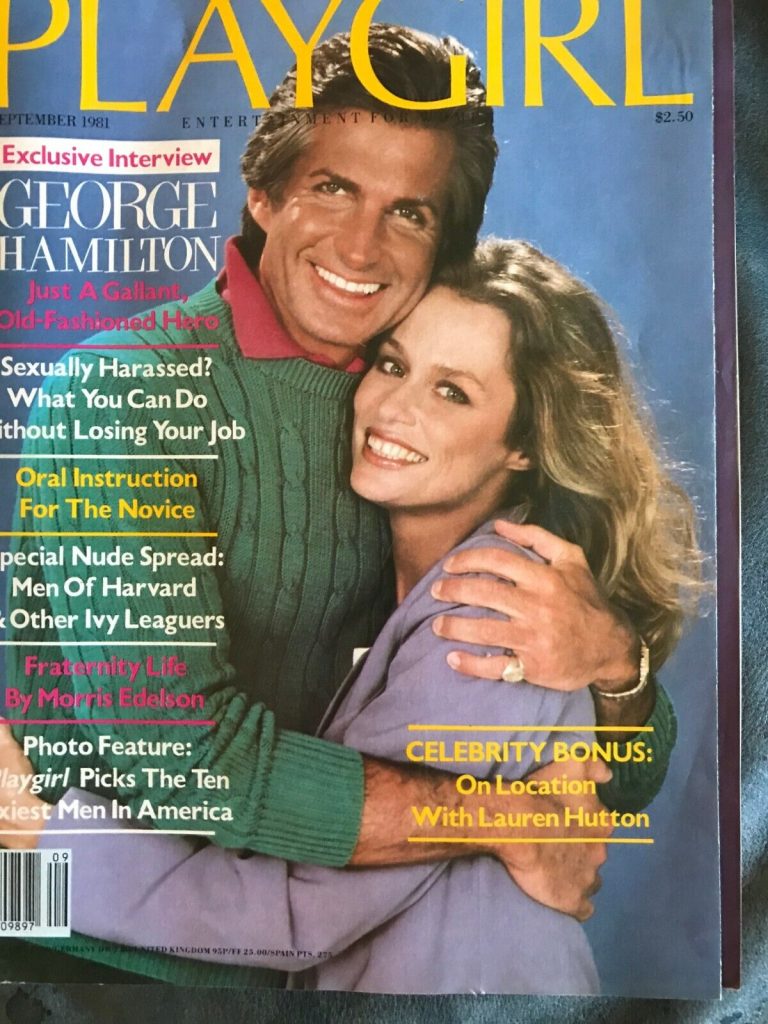

From the 1970s on George tended to be tux-prone on standard film and TV comedy and drama, whether as a martini-swirling opportunist, villain or lover. A wonderful comeback for him came in the form of the disco-era Dracula spoof Love at First Bite (1979), which he executive-produced. Nominated for a Golden Globe as the campy neck-biter displaced and having to fend off the harsh realities of New York living, he continued on the parody road successfully with Zorro: The Gay Blade (1981) in the very best Mel Brooks tradition.

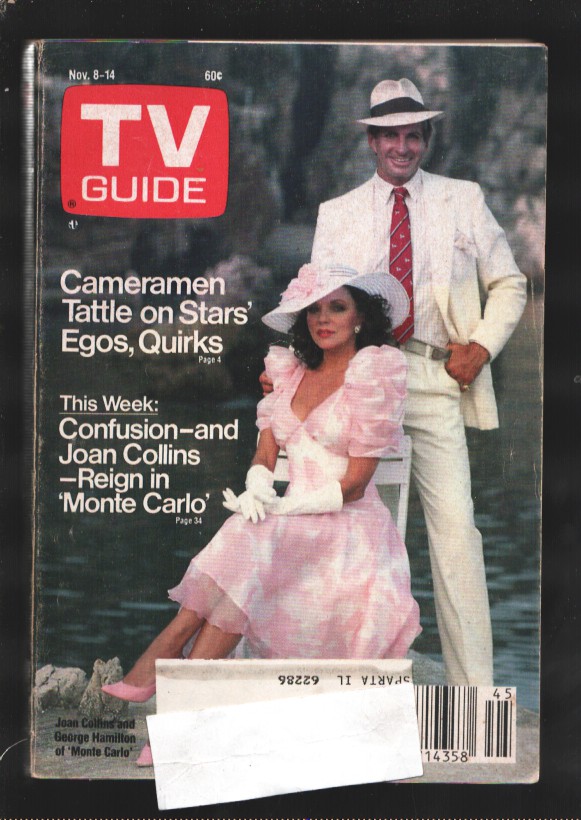

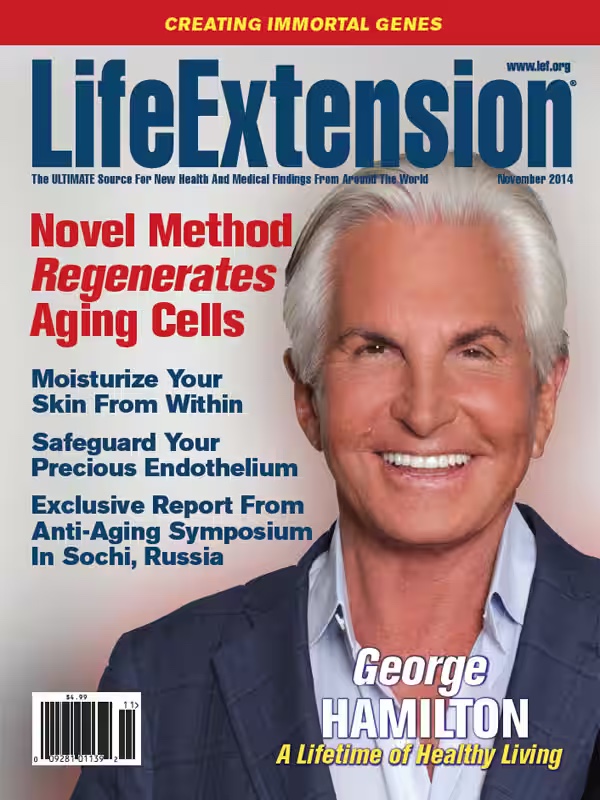

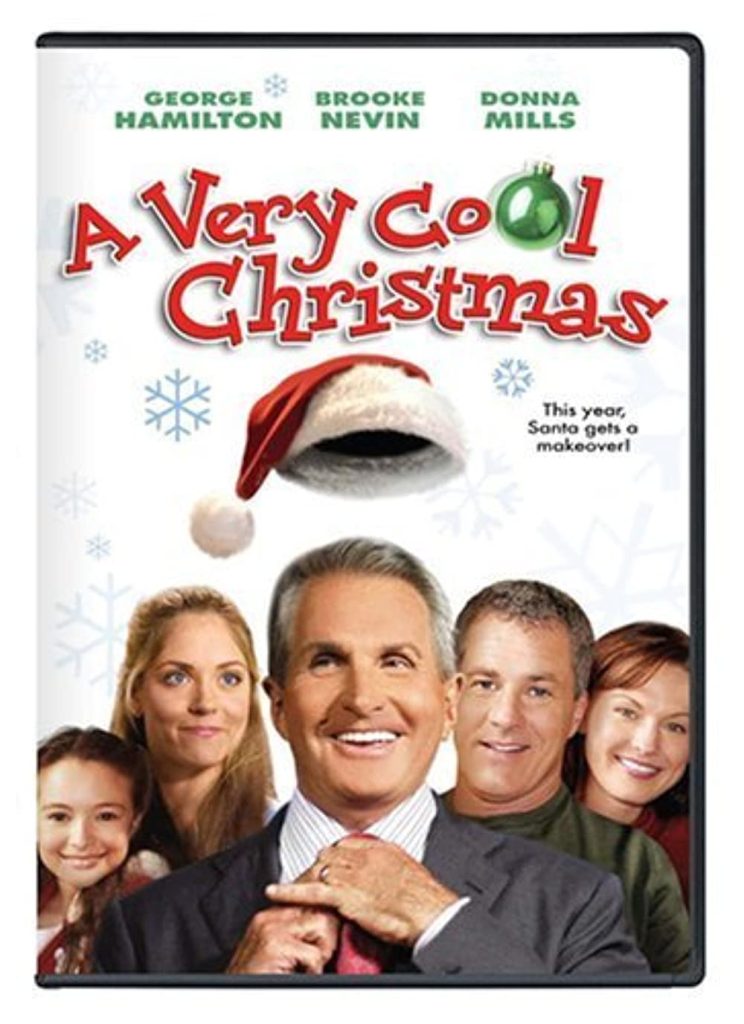

This renewed popularity led to a one-year stint on Dynasty (1981) during the 1985-1986 season and a string of fun, self-mocking commercials, particularly his Ritz Cracker and (Toasted!) Wheat Thins appearances that often spoofed his overly tanned appearance. In recent times he has broken through the “reality show” ranks by hosting The Family(2003), which starred numerous members of a traditional Italianate family vying for a $1,000,000 prize, and participating in the second season of ABC’s Dancing with the Stars(2005), where his charm and usual impeccable tailoring scored higher than his limberness. On the tube he can still pull off a good time, whether playing flamboyant publisher William Randolph Hearst in Rough Riders (1997), playing the best-looking Santa Claus ever in A Very Cool Christmas (2004), hosting beauty pageants or making breezy gag appearances.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net