Jane Wyman won an Oscar in 1948 for her performance in “Johnny Belinda”. She had spent a long time in small parts in movies and htis film was one of her first starring parts. She had a good ten years as a major leading lady. She was retired for a number of yearswhen she made it big again in the 1980’s with the success of the television series “Falcoln Crest” where she played the matriarch Angela Channing. When the series ended she retired again. She died at the age of 90 in 2007. Jane Wyman was the first wife of Ronald Reagan. Her biography on IMDB can be found here.

Jane Wyman obituary in “The Independent”.

Her “Independent” obituary:

The Oscar-winning actress Jane Wyman, who married the future US president Ronald Reagan when he was still an actor, was a prime example of a film star who paid her dues in the days of the studio system. As a contract player at Warner Bros, she appeared in more than 40 films before achieving star billing, two years after which she won an Academy Award for her moving portrayal of a deaf mute in Johnny Belinda (1948), which heralded a long career as a major star. Best remembered for films in which she suffered nobly, she also shone in comedy, and she could sing too – with Bing Crosby she introduced the Oscar-winning song “In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening”. The director Alexander Hall said, “That gal can do anything she sets her mind to; she is one of the most creatively versatile performers the screen has ever boasted.”

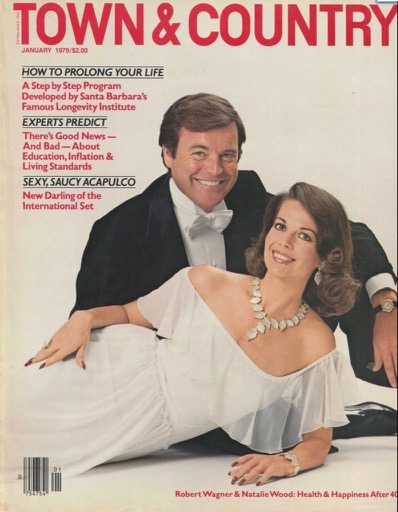

A new generation acclaimed her as the matriarch of the television series Falcon Crest. Her place in history is assured, since Reagan was the first US President to have an ex-wife, and though neither liked to talk about their marriage, many contend that he would never have become President had she not left him. “I was divorced in the sense that the decision was made by somebody else,” he once said.

Wyman’s early life is somewhat contentious. Records would indicate that she was born Sarah Jane Mayfield, daughter of Manning J. Mayfield, a labourer at a food company, and Gladdys Hope Christian, in St Joseph, Missouri, in 1917. Her parents, who married in 1916, were divorced in 1921, and Manning died the following year. Gladdys then gave her daughter into the care of Richard Fulks and his German-born wife, the former Emma Reiss. There seems to have been no formal adoption or name change, but when the child was registered for first grade at the Noyes School in St Joseph, Emma listed her name as “Sarah Jane Fulks”.

Wyman later revealed that she loathed school, but her spirited response to dance classes prompted Mrs Fulks to take her to Hollywood at the age of eight, but without success. “I was one of those blonde curly-haired kids and my mother thought I was destined for the movies,” she recalled. The couple returned home, and Jane later reflected, “I was raised with such strict discipline that it was years before I could reason myself out of the bitterness I brought from my childhood.”

She worked as a switchboard operator, waitress and manicurist before trying Hollywood again – she now had a contact, since her dancing instructor in Missouri was the father of the leading film choreographer Leroy Prinz, who gave her a spot in Busby Berkeley’s The Kid from Spain (1932). For the next four years, she toiled in the chorus, occasionally getting a line of dialogue, and she can be spotted in College Rhythm (1934), Rumba (1935), King of Burlesque (1935) and Anything Goes (1936). Finally, she won a contract with Warners in 1936, on the recommendation of the agent and actor William Demarest. The studio is often credited with naming her “Jane Wyman”, but some sources aver that the actress was briefly married in 1931 to a student named Eugene Wyman, while another explanation is that Mrs Fulks had been married before, and her first husband’s name was M.F. Weyman.

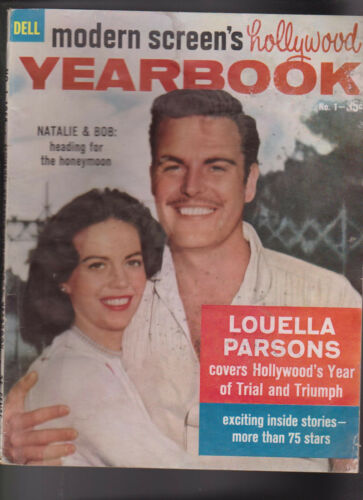

Warners put Wyman to work with a string of bit parts – wise-cracking girl friends, telephonists, secretaries, chorus girls – that would lead to starring roles in “B” movies with, it seemed, little chance of rising higher, though Dick Powell, who starred in three films that featured Wyman, stated, “Janie had something you couldn’t learn – presence.” The director William Keighley reflected, “I was surprised big things didn’t happen for the Wyman girl a lot faster than they did.” William Demarest was to say of Wyman’s lifestyle during those years, “She couldn’t keep still for a second, loved nightclubs, dancing, singing with her friends. ‘There’s a lot of living to be done, and I’m going to do it,’ she’d say.” Her penchant for elaborate clothes and costume jewellery prompted gossip columnist Louella Parsons to call her “a walking Christmas tree”. In 1937 Wyman married Myron Futterman, a dress manufacturer and divorcee with a teenage daughter, but the marriage lasted only a year.

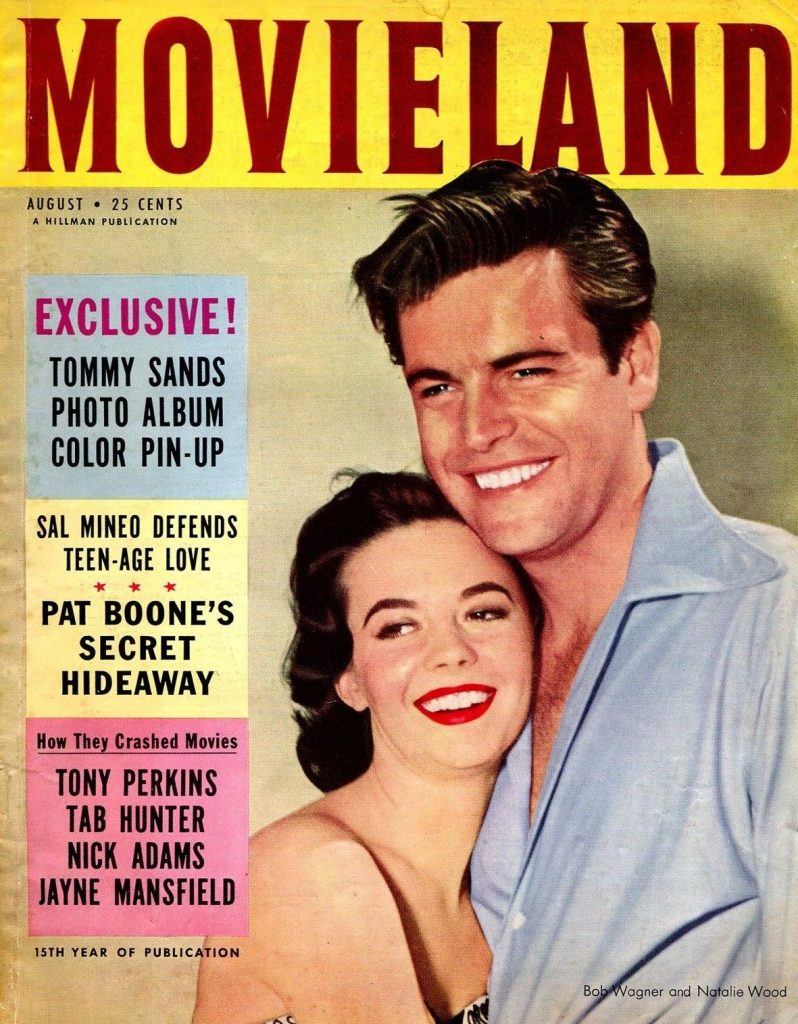

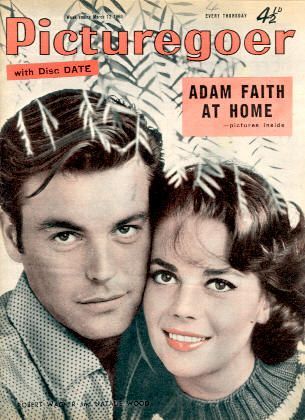

Wyman was given her first leading role in a “B” movie titled Public Wedding (1937), and around this time she met a new contract player, the former radio sports announcer Ronald Reagan. She confessed later that she was attracted to the actor and flirted with him, but he would not consider a relationship because, although separated, she was still married. Demarest said, “She was far more worldly and experienced than he was, although she was three years his junior. I think Ronnie at first was somewhat bewildered by her fast come-on; then he started to like it, then her, and then he fell in love.”

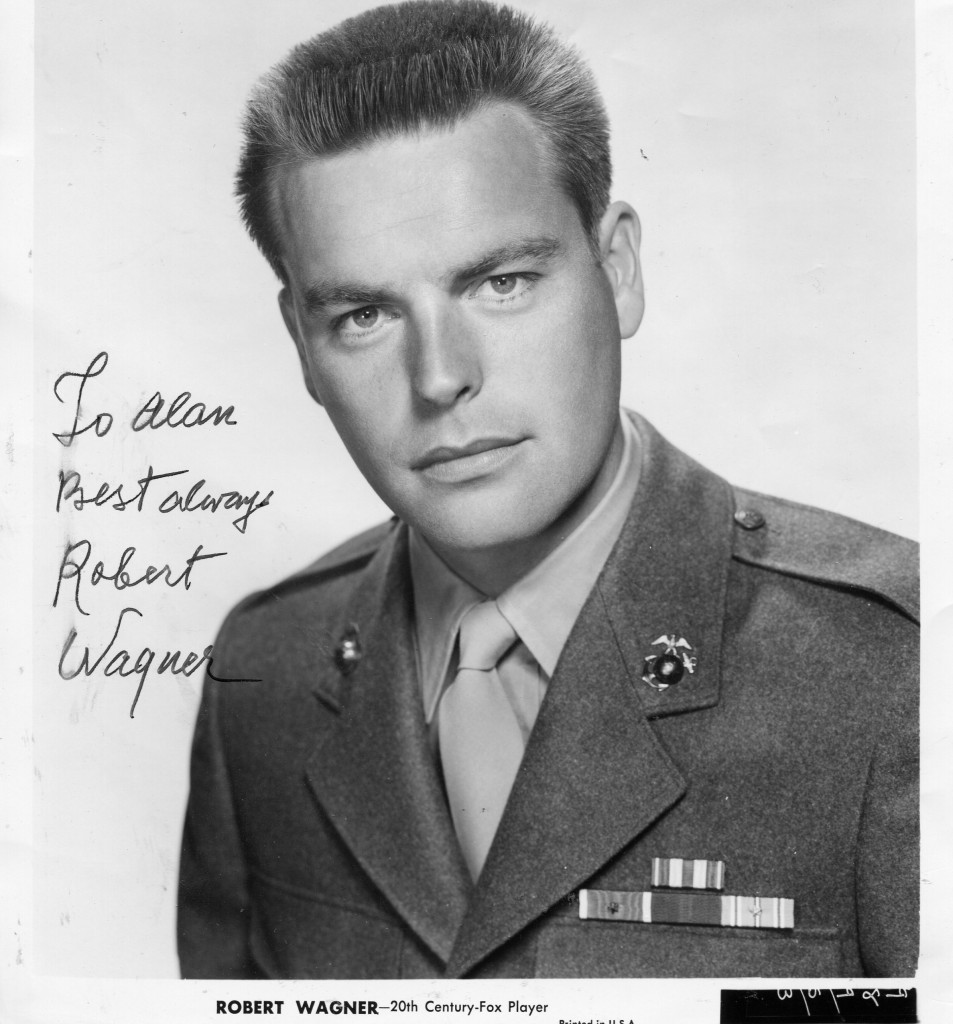

Their relationship flourished during the shooting of William Keighley’s Brother Rat (1938), in which they played a marine cadet and his sweetheart. Wyman and Reagan were total opposites. He was an outdoor enthusiast and an ardent Democrat who was soon involved in the Screen Actors Guild, fighting for the rights of contract players. Wyman was apolitical, stating, “When I first met Ronnie I was a nightclub girl. I just had to go dancing and dining every night to be happy.”

By the time Reagan proposed to her – on the set of a sequel, Brother Rat and a Baby (1940) – Wyman had developed some interest in politics and athletics, and had even taken up golf, an enthusiasm she retained for the rest of her life. Meanwhile she had supported Alice Faye in Tailspin (1939) and starred as resourceful reporter Torchy Blane in Torchy Plays with Dynamite (1939).

Wyman and Reagan were wed in 1940. Their daughter, Maureen, was born in 1941, and in 1945 they adopted a baby boy, Michael. While Reagan’s career seemed to be going upwards, Wyman’s followed its familiar pattern. “I’m queen of the sub-plots,” she confessed. “For years I’ve been the leading lady’s confidante, adviser, pal, sister, severest critic.”

Drafted when the United States entered the Second World War, Reagan was stationed with an army film unit in Culver City, where he was a personnel officer when not acting in training films. Wyman toured military camps, using a talent for singing that she had rarely displayed on screen. Knowing that the studio had purchased the rights to the life story of torch singer Helen Morgan, Wyman campaigned for the role but was instead cast in support of Ann Sheridan in The Doughgirls (1944). Sheridan had become one of her closest friends, and commented, “Jane used to tell me that Ronnie was such a talker that he even made speeches in his sleep.”

Wyman’s career received a boost when Billy Wilder asked her to read the screenplay he and Charles Brackett had fashioned from Charles Jackson’s novel about alcoholism, The Lost Weekend, to be filmed for Paramount. She said, “I was so conditioned to think of myself as a comedienne, I was completely floored when Billy said he wanted me for the part of girlfriend to the hero.” Brackett said, “We wanted a girl with a gift for life. We needed some gusto in the picture.” (He omitted to tell Wyman that both Katharine Hepburn and Jean Arthur had turned down the role.)

Wilder and Brackett’s adaptation omitted the hero’s latent homosexuality, enlarged the part of the girl, and added an optimistic ending, but otherwise it was an uncompromising and brilliant study of a hopeless alcoholic (an Oscar-winning Ray Milland), with Wyman splendid as his down-to-earth sweetheart. “It changed my whole life,” said Wyman, though she was still under-rated by her own studio and found herself cast as a chirpy chorus girl in a wildly inaccurate biography of Cole Porter, Night and Day (1946).

Though release of The Lost Weekend was delayed for nearly a year – the studio had qualms about it, and the liquor industry offered them $5m to destroy the negative – trade insiders had seen it, and MGM negotiated to borrow Wyman for their screen version of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about a boy’s love for a fawn, The Yearling. Its star Gregory Peck, who personally acted with Wyman in her test, told her afterwards, “You were wonderful”, to which she replied, “Good God, don’t act so surprised.” When The Lost Weekend opened, critics displayed similar wonder. The World-Telegram referred to her “unsuspected talent” and The New York Times stated, “Jane Wyman assumes with great authority a different role.”

Her part in The Yearling (1947) as careworn Ma Baxter, who toils in the backwoods of 1870 Florida, required delicate shading in her portrayal of a mother who must have her son’s beloved fawn killed because it is eating their crops. Wyman’s performance was described by Life magazine as “beyond reproach”. Wyman won an Oscar nomination and, though she lost to Olivia De Havilland in To Each His Own, her status as a star was now established, and she was soon to play the part for which many best remember her.

The producer Jerry Wald had persuaded Warners to buy the rights to a Broadway hit of 1940, Johnny Belinda, despite the studio’s misgivings about a story in which a deaf mute is raped, has a child, then kills the father when he tries to take it from her. (Shortly before shooting commenced in late 1947, Wyman’s second child, a daughter, had died a few hours after her premature birth.) Wyman learned sign language and lip reading for the film, but later recalled, “Something was missing. Suddenly I realised what was wrong. I could hear.”

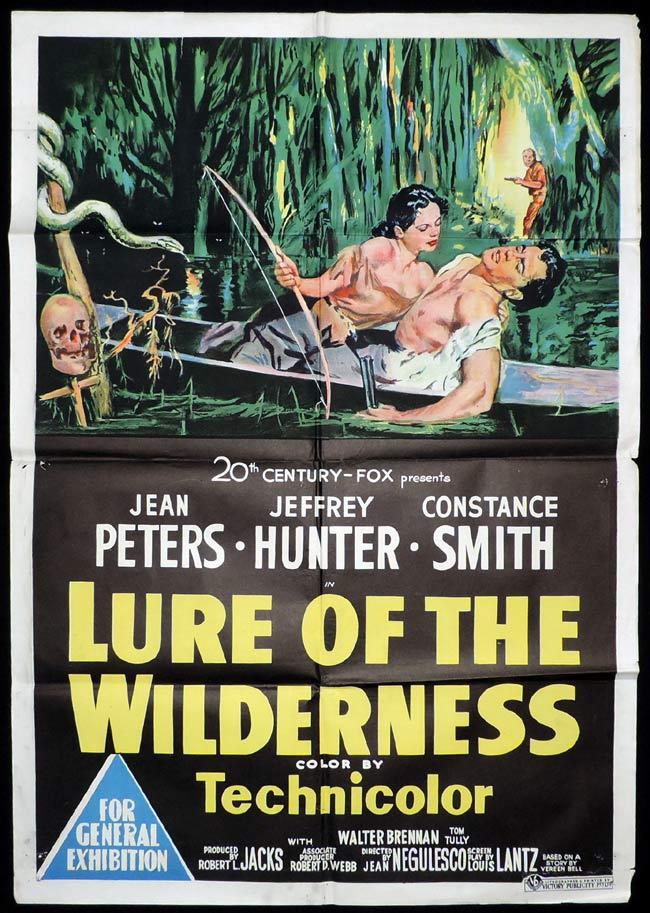

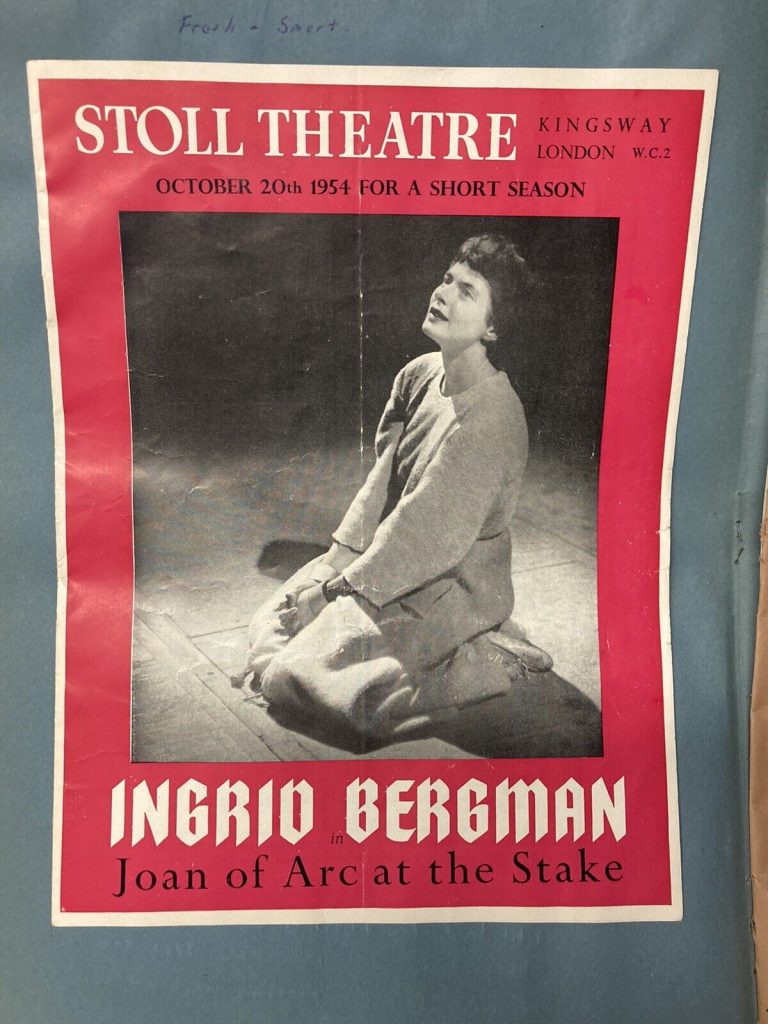

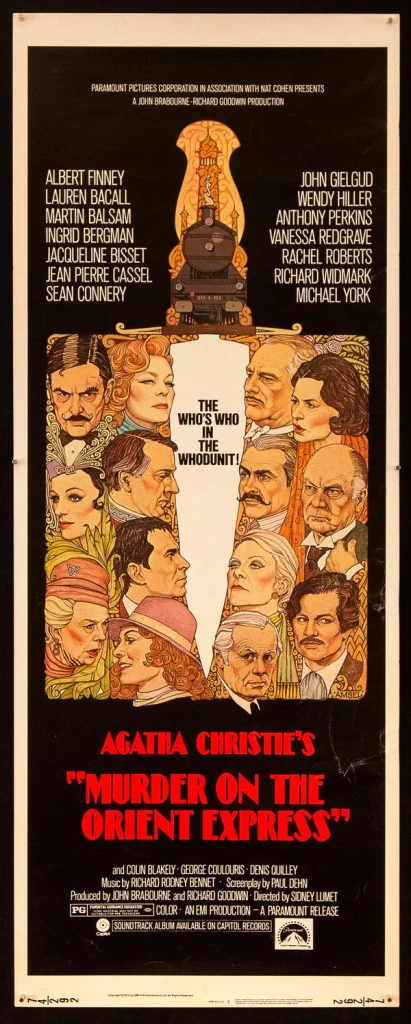

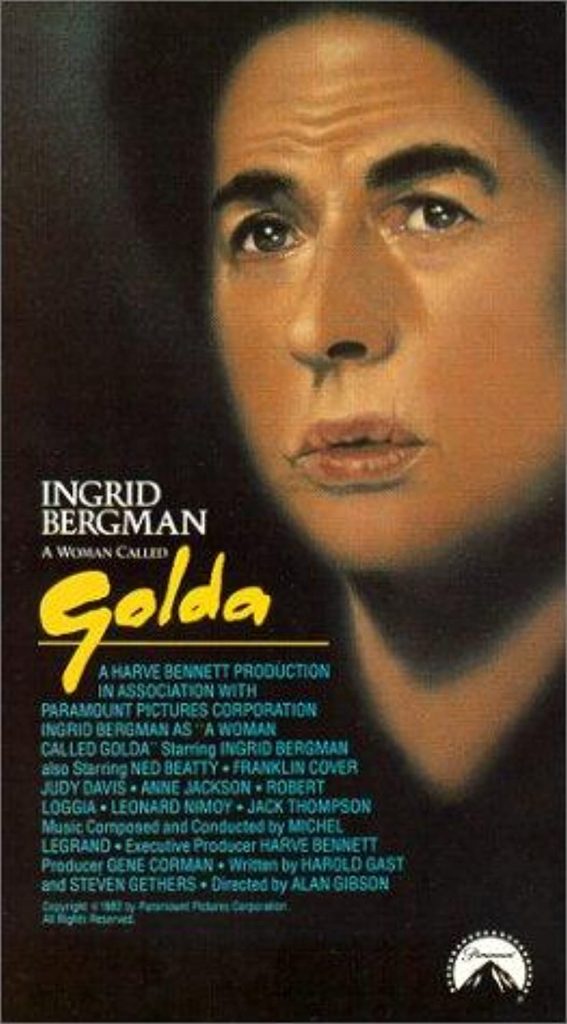

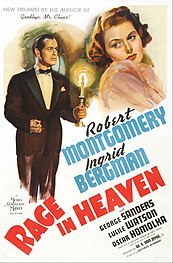

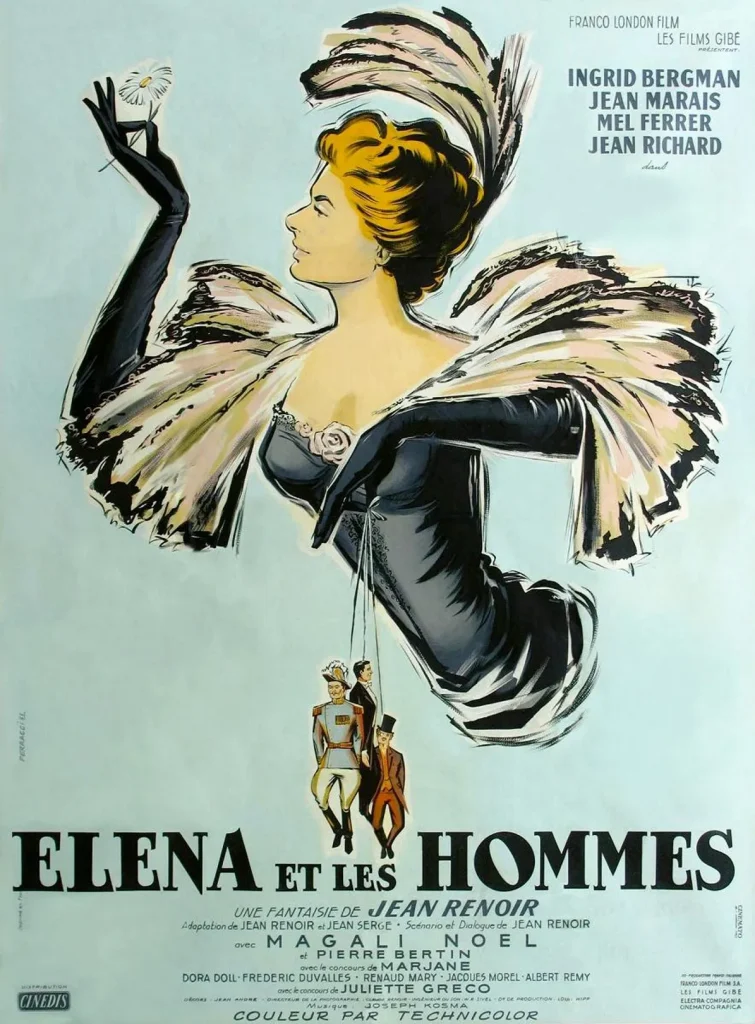

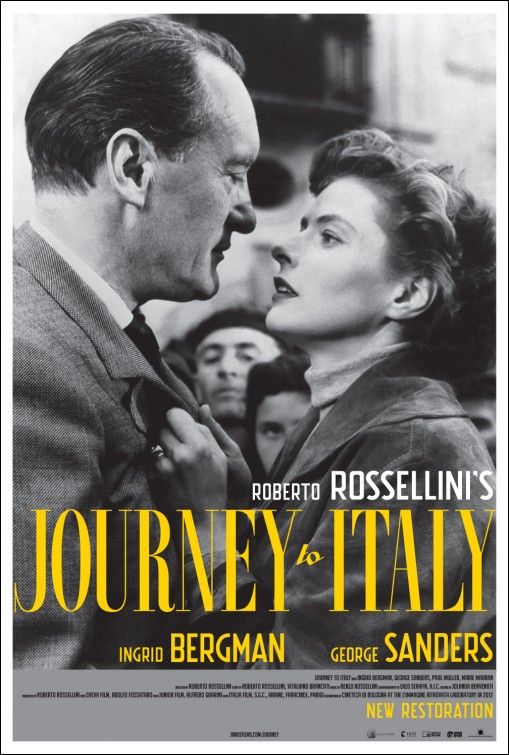

She and the director Jean Negulesco decided that her ears should be blocked with wax to cut out all noise except percussion. Wyman’s performance was beautifully modulated, avoided bathos, and won her a deserved Oscar against formidable competition (Ingrid Bergman, Barbara Stanwyck, Olivia De Havilland and Irene Dunne). Her acceptance speech was one of the briefest and most effective in Oscar’s history: “I accept this award very gratefully – for keeping my mouth shut for once. I think I’ll do it again.”

She was accompanied to the ceremony by the actor Lew Ayres, who was rumoured to have consoled her during the shooting because of her marital problems. Reagan’s political work and fervent campaigning for President Truman had strained their relationship, but when Wyman announced to the press, “We’re through. We’re finished. And it’s all my fault”, she was making it clear that it was her own decision to end the marriage. “I love Jane,” said Reagan, “and I know she loves me. I don’t know what this is all about and I don’t know why Jane has done it.”

Shortly afterwards, Reagan was in London filming The Hasty Heart, and his co-star Patricia Neal later commented, “Although I was a young, pretty girl, he never made a pass at me. Of course there were splendid reasons. I was wildly in love with Gary Cooper and he was still in love with Jane Wyman.” The couple’s divorce became final in July 1949. Wyman refused throughout her life to talk of their marriage or divorce, claiming that it was “bad taste” to discuss such matters.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (1950) took Wyman to London where she renewed a friendship with Laurence Olivier, who had won his Oscar for Hamlet on the same night she won hers. Hitchcock had personally asked for Wyman, but he was later to accuse her of getting out of character by refusing to look too drab compared to her glamorous co-star, Marlene Dietrich. The film’s lukewarm reviews, though, were the fault of the director, who made a rare error of judgement by opening the mystery with Wyman’s boyfriend (Richard Todd) relating an incident told in flashback (in an era when flashbacks were taken literally) though in fact he is lying. Critics were incensed by the perceived “cheating”, and the film proved a box-office disappointment.

The Glass Menagerie (1950), based on Tennessee Williams’ lyrical play, also proved disappointing, though Wyman gave what The New York Times called a “beautifully sensitive” portrayal of Laura, a crippled girl who finds solace from loneliness in her collection of glass figurines.

In 1952 Wyman had two contrasting box-office hits. The first was Frank Capra’s musical comedy, Here Comes the Groom, in which Wyman was teamed with her singing idol, Bing Crosby. The pair had relaxed fun with a novelty number, “In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening”, which Hoagy Carmichael and Johnny Mercer had written for an unrealised Betty Hutton musical based on the life of Mabel Normand. It was a complicated production number that took the couple through several sets as they sang, and Capra decided to record the song live, with tiny radios in the stars’ ears so that they could hear the orchestra. The song won an Oscar, the stars’ recording was a big hit, and Decca signed Wyman to a recording contract. Her co-star Franchot Tone said, ‘Everybody got caught up in the fun Bing and Jane were obviously having together.’

The producer Jerry Wald had bought the rights to a French film hit, Le Voile Bleu (1947), hoping to tempt Greta Garbo out of retirement to play a woman who loses her husband and child in the First World Warand devotes her life to being governess to other people’s children. When Garbo refused, he asked Wyman to take the role, in which the woman goes from home to home until, old and working as a janitor, she is given a surprise party attended by all her former progeny. It was blatantly manipulative, but Wyman brought dignity and conviction to her part. Variety called it “a personal triumph”, and The Blue Veil won Wyman her third Oscar nomination, though she was up against two powerhouse performances, Katharine Hepburn’s in The African Queen, and Vivien Leigh’s (the winner) for A Streetcar Named Desire.

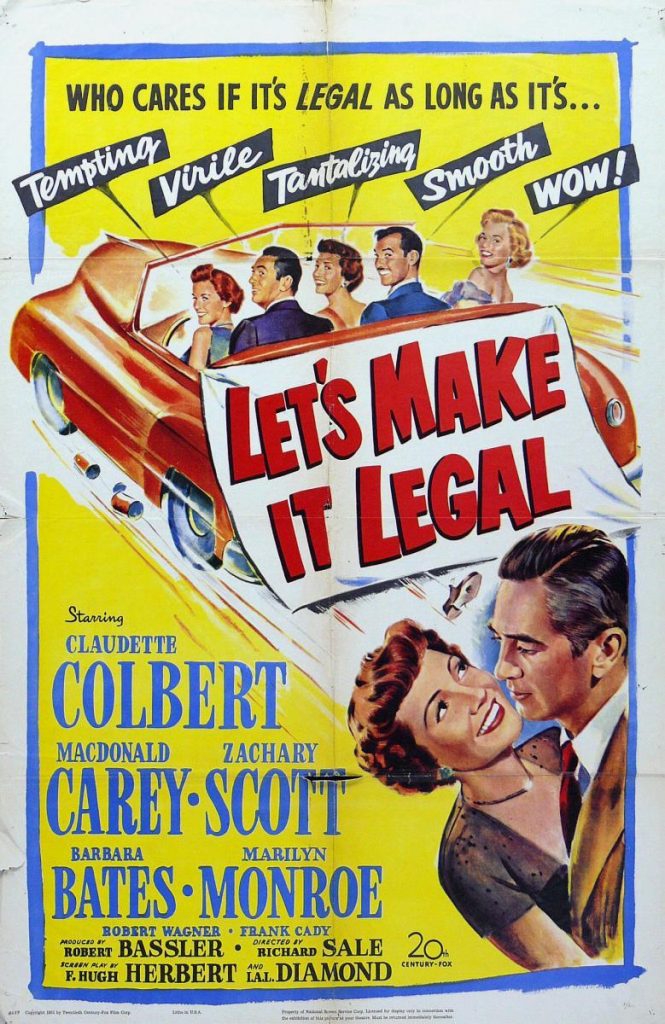

The success of both Here Comes the Groom and The Blue Veil put Wyman into the year’s top ten box-office draws, and she won two Golden Globe awards – as best actress, for The Blue Veil and as “World Film Favourite Actress of the year”. Wyman rejoined Crosby to take a role planned for Judy Garland (who was not fit enough to do it) in Just for You (1952). Its brightest spot was another catchy duet with Crosby. Wyman was reunited with Ray Milland for Let’s Do It Again (1952), a musical remake of a comedy classic, The Awful Truth. Milland, usually sparing with compliments, said of Wyman, “She could sing and dance with the best of them and her comedy timing was top-notch. She inspired everyone around her to give their best, and she was very down-to-earth and democratic.”

Making the film, Wyman met Fred Karger, an assistant to the studio’s music director, Morris Stoloff, and before shooting finished, Karger had become Wyman’s husband. They were divorced in 1955, remarried in 1961, and divorced again in 1965.

Wyman had to go from young woman to old lady again in Robert Wise’s So Big (1953), the third screen version of Edna Ferber’s novel. It proved popular, but not as much as her next film, another property filmed twice before, Magnificent Obsession (1954). In this, the first of a string of lush melodramas produced by Ross Hunter, wastrel Rock Hudson indirectly causes both the death of Wyman’s doctor husband and then Wyman’s blindness. Reformed, he becomes a surgeon and restores Wyman’s sight for a tearful climax. Most critics directed any praise they offered to Wyman’s sincere underplaying, which won her a fourth Oscar nomination (she lost to Grace Kelly in The Country Girl).

Directed by Douglas Sirk, the film was a huge money-maker, though it is less well regarded today than another film with the same production team and stars, All That Heaven Allows (1955). The latter, in which a widow falls in love with her young gardener to the horror of her selfish children and her conformist friends, was dismissed by most critics as just another piece of glossy kitsch, but is now perceived as a cuttingly perceptive attack on middle-class hypocrisy and the expectation that ageing widows should need nothing more from life than the country club and a TV set.

It was not entirely original (My Reputation had tackled a similar subject a decade earlier) but Sirk’s subversion of his material and use of colour made his film more than just a star vehicle. (In a celebrated shot, he has Wyman’s face reflected in the glass screen of the television to symbolise her entrapment.) Fassbinder’s Fear Eats the Soul (1974) was inspired by the film, though his ending was much bleaker.

In 1955, after starring with Van Johnson in the sentimental Miracle in the Rain, Wyman refused the role of Gary Cooper’s wife in Friendly Persuasion, and instead became president of the company that produced the television anthology series Fireside Theater. Rechristened The Jane Wyman Theater, it featured a variety of plays, with Wyman starring in around a third of each season’s 34 half-hour episodes, and ran until 1959. For the next 22 years, she made occasional guest appearances in TV shows such as Wagon Train and The Love Boat, and played only four more film roles, notably as Hayley Mills’ stern Aunt Polly in Pollyanna (1960). Semi-retired, she enjoyed painting, golf and seeing her children.

Her career, it seemed, was virtually over when in 1981, at the age of 64, she was asked to star as Angela Channing, wine tycoon, in the television series Falcon Crest. The “pilot” show left her with stringent demands. “Not only was Angela too mean and vicious, but she was just plain boring. I wanted her to be an interesting character.” When the former superstar Lana Turner joined the show as Wyman’s sister-in-law, Turner’s entourage and star demands did not sit well with Wyman, who displayed her power by having Turner’s character killed off after one season. Falcon Crest ran until 1990, and by the end of the show’s fifth season, the already-wealthy Wyman was estimated to be earning $3m a year (10 times Reagan’s salary).

When Reagan died in 2004, Wyman broke her long silence to say, “America has lost a great President and a great, kind and gentle man.”

Tom Vallance

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.