Ingrid Bergman won three Oscars, “Gaslight”, “Anastasia” and “Murder on the Orient Express. She began her career in her native Sweden and became a top Hollywood star in the 1940’s. At the heigth of her fame in 1949 she left Hollywood and made films in Italy. She returned to the U.S. in 1956 and resumed her international career. She died on her 67th birthday in London. Her most iconic role is as Ilsa Lund in “Casablanca” opposite Humphrey Bogart.

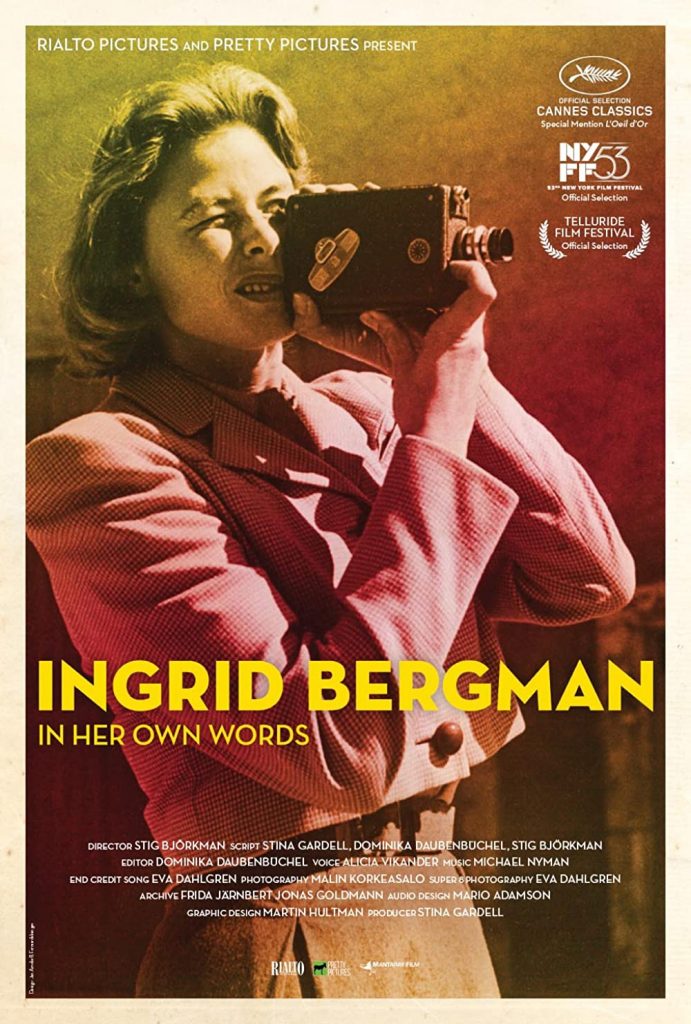

TCM Overview:

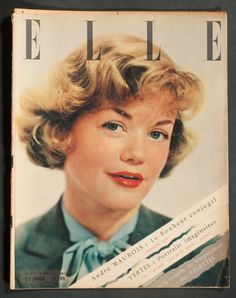

A highly popular actress known for her fresh, radiant beauty, Ingrid Bergman was a natural for virtuous roles but equally adept at playing notorious women. Either way, she had few peers when it came to expressing the subtleties of romantic tension. In 1933, fresh out of high school, she enrolled in the Royal Dramatic Theater and made her film debut the following year, soon becoming Sweden’s most promising young actress. Her breakthrough film was Gustaf Molander’s “Intermezzo” (1936), in which she played a pianist who has a love affair with a celebrated–and married–violinist. The film garnered the attention of American producer David O. Selznick, who invited her to Hollywood to do a remake. In 1939 she co-starred with Leslie Howard in that film, which the public loved, leading to a seven-year contract with Selznick

“New York Times” obituary:

Ingrid Bergman, the three-time Academy Award-winning actress who exemplified wholesome beauty and nobility to countless moviegoers, died of cancer Sunday at her home in London on her 67th birthday.

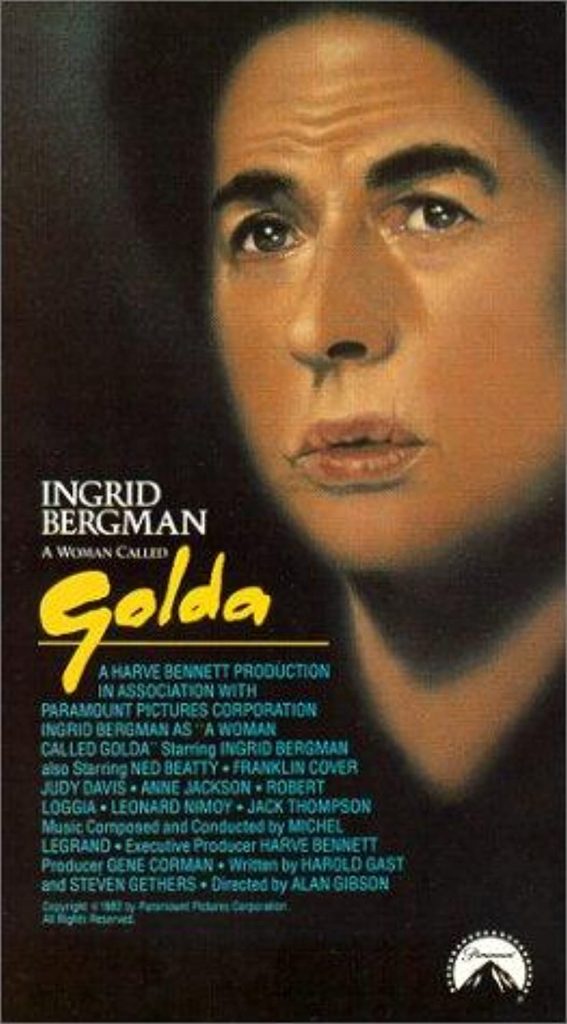

Miss Bergman had been ill for eight years. Despite this, she played two of her most demanding roles in this period, a concert pianist in Ingmar Bergman’s ”Autumn Sonata” and Golda Meir, the Israeli Prime Minister in ”A Woman Called Golda.” her last role.

Miss Bergman said in an interview earlier this year that she was determined not to let her illness prevent her from enjoying the remainder of her life.

”Cancer victims who don’t accept their fate, who don’t learn to live with it, will only destroy what little time they have left,” she said. Miss Bergman added that she had to push herself to play the role of Golda Meir: ”I honestly didn’t think I had it in me. But it has been a wonderful experience, as an actress and as a human being who is getting more out of life than expected.”

Lars Schmidt, a Swedish producer from whom Miss Bergman was divorced in 1975, was with her at the time of her death. Incandescent, the critics called Ingrid Bergman. Or radiant. Or luminous. They said her performances were sincere, natural. Sometimes a single adjective was not enough. One enraptured writer saw her as ”a breeze whipping over a Scandinavian peak.” Kenneth Tynan needed an essay before he distilled her quality down to a sort of electric transmission of ”I need you” that registered instantly upon yearning audiences.

At the heart of the Swedish star’s monumental box-office magnetism was the kind of rare beauty that Hollywood cameramen call ”bulletproof angles,” meaning it can be shot from any angle.

Her beauty was so remarkable that it sometimes seemed to overshadow her considerable acting talent. The expressive blue eyes, wide, fulllipped mouth, high cheekbones, soft chin and broad forehead projected a quality that combined vulnerability and courage; sensitivity and earthiness, and an unending flow of compassion.

It all seemed so natural that not until she was well into middle age, in Ingmar Bergman’s taxing ”Autumn Sonata” in 1978, did many of her fans fully realize the talent, work and intelligence that were behind the performances that won her three Academy Awards.

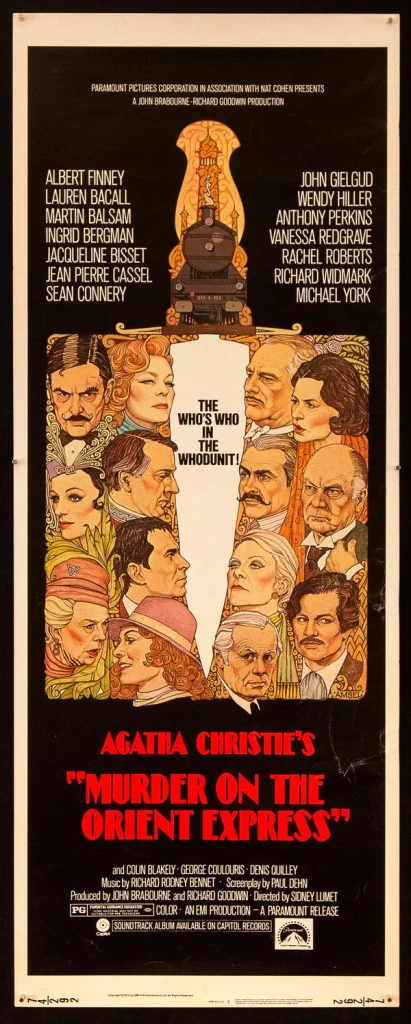

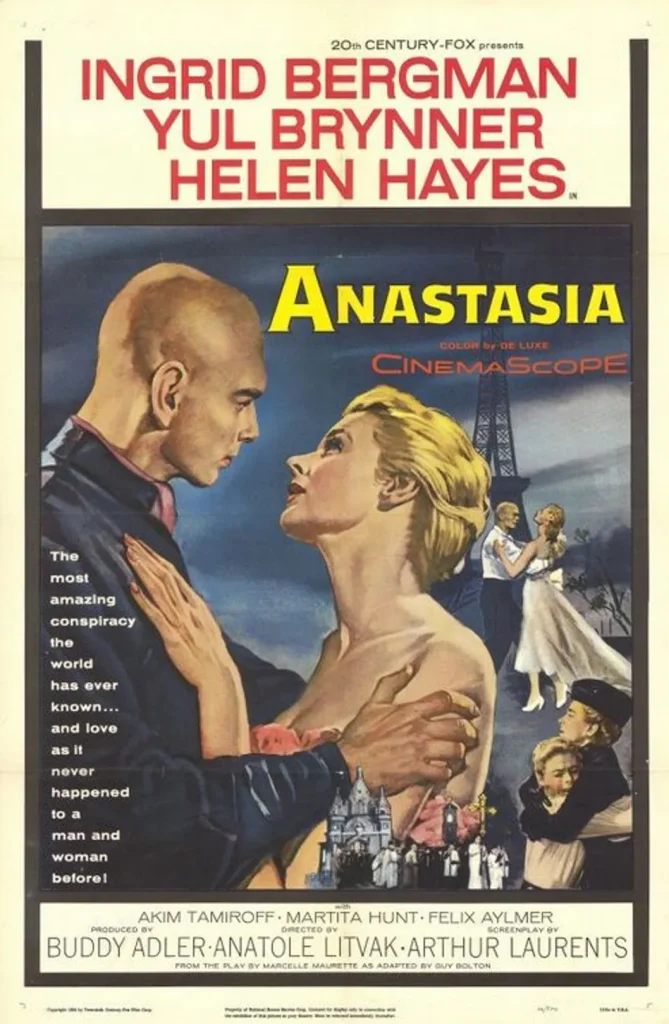

She was honored as best actress for her roles in ”Gaslight” in 1944 and ”Anastasia” in 1956, and as best supporting actress in ”Murder on the Orient Express” in 1974.

In temperament, Miss Bergman was different from most Hollywood superstars. She did not indulge in tantrums or engage in harangues with directors. If she had a question about a script, she asked it without fuss. She could be counted on to be letter perfect in her lines before she faced the camera. And during the intervals between scenes, her relaxing smile and hearty laugh were as unaffected as her low-heeled shoes, long walking stride and minimal makeup.

Yet this even-tempered and successful actress, who was apparently happily married, became involved in a scandal that rocked the movie industry, forced her to stay out of the United States for seven years and made her life as tempestuous as many of her roles. In a sense, she became a barometer of changing moral values in the United States.

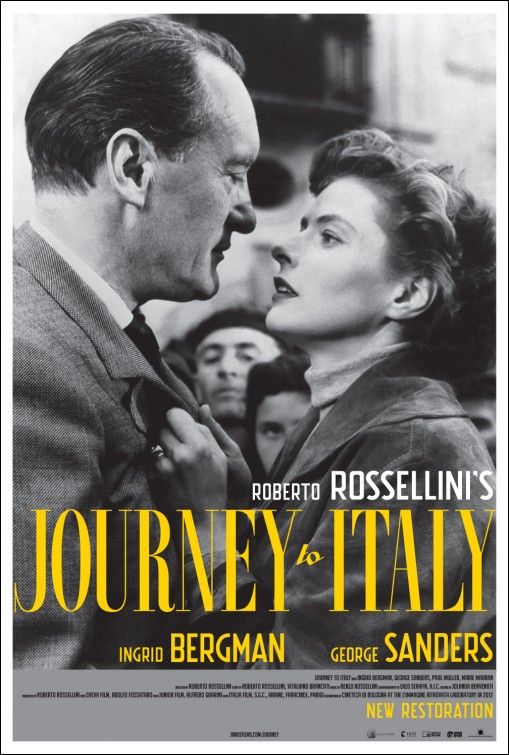

In 1949 she fell in love with Roberto Rossellini, the Italian film director, and had a child by him before she could obtain a divorce from her husband, Dr. Peter Lindstrom, and marry the director.

Symbol of Moral Perfection

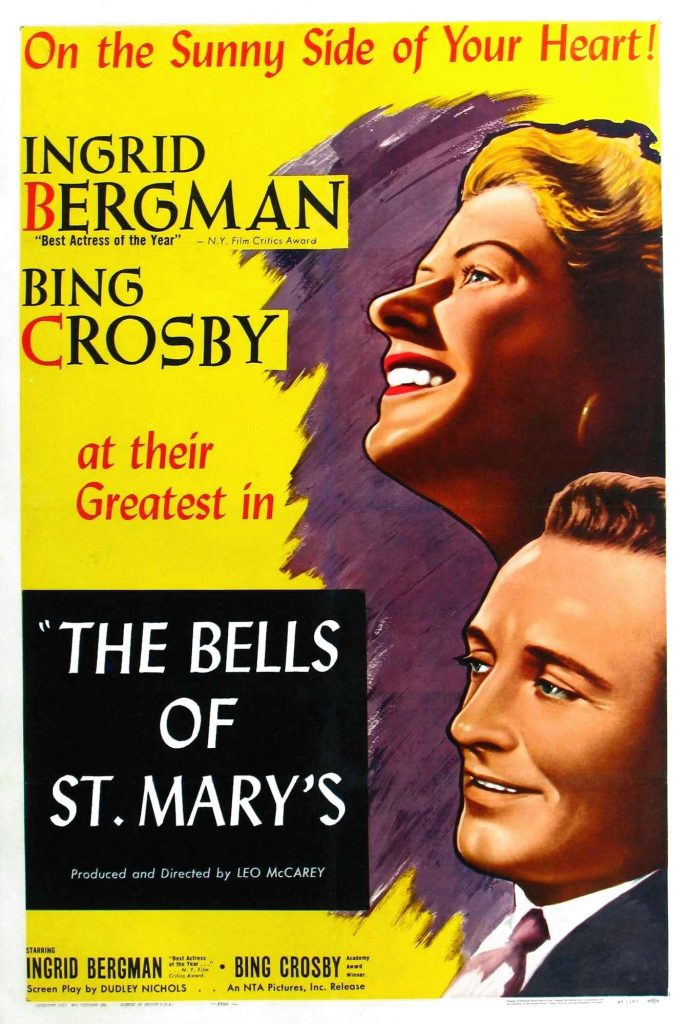

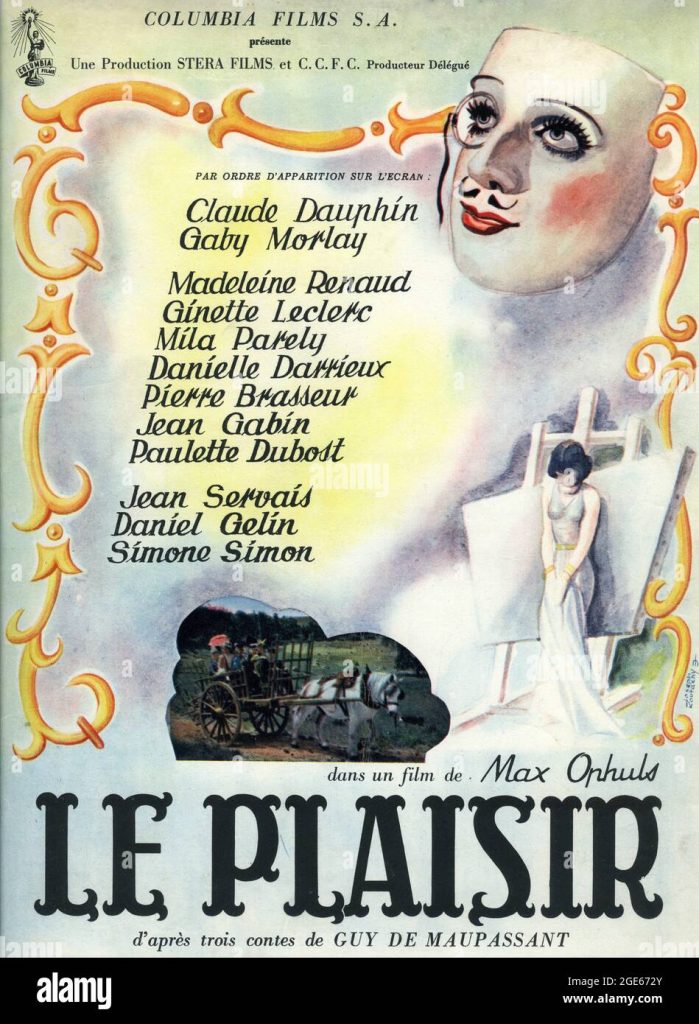

Before the scandal, millions of Americans had been moved by her performances in such box-office successes as ”Intermezzo,” ”For Whom the Bell Tolls,” ”Gaslight,” ”Spellbound,” ”The Bells of St. Mary’s,” ”Notorious” and ”Casablanca,” roles that had made her, somewhat to her annoyance, a symbol of moral perfection.

”I cannot understand,” she said, long before the scandal, ”why people think I’m pure and full of nobleness. Every human being has shades of bad and good.”

Suddenly, in 1949, the American public that had elevated her to the point of idolatry cast her down, vilified her and boycotted her films. She was even condemned on the floor of the United States Senate.

Then, seven years after she had fallen from grace in this country, she returned to gather new acclaim and honors for her acting, and she never again suffered any noticeable loss of favor as an actress or as a person. But she spent nearly all of her remaining working life in Europe, sometimes for American movie companies.

So complete was Miss Bergman’s victory that Senator Charles H. Percy, Republican of Illinois, entered into the Congressional Record, in 1972, an apology for the attack made on her 22 years earlier in the Senate by Edwin C. Johnson, Democrat of Colorado.

By this time Miss Bergman had already expressed publicly her feelings and philosophy. Upon her return to the United States in 1956, for the first time since her departure, she told a jammed airport press conference, in English, Swedish, German, French and Italian:

”I have had a wonderful life. I have never regretted what I did. I regret things I didn’t do. All my life I’ve done things at a moment’s notice. Those are the things I remember. I was given courage, a sense of adventure and a little bit of humor. I don’t think anyone has the right to intrude in your life, but they do. I would like people to separate the actress and the woman.”

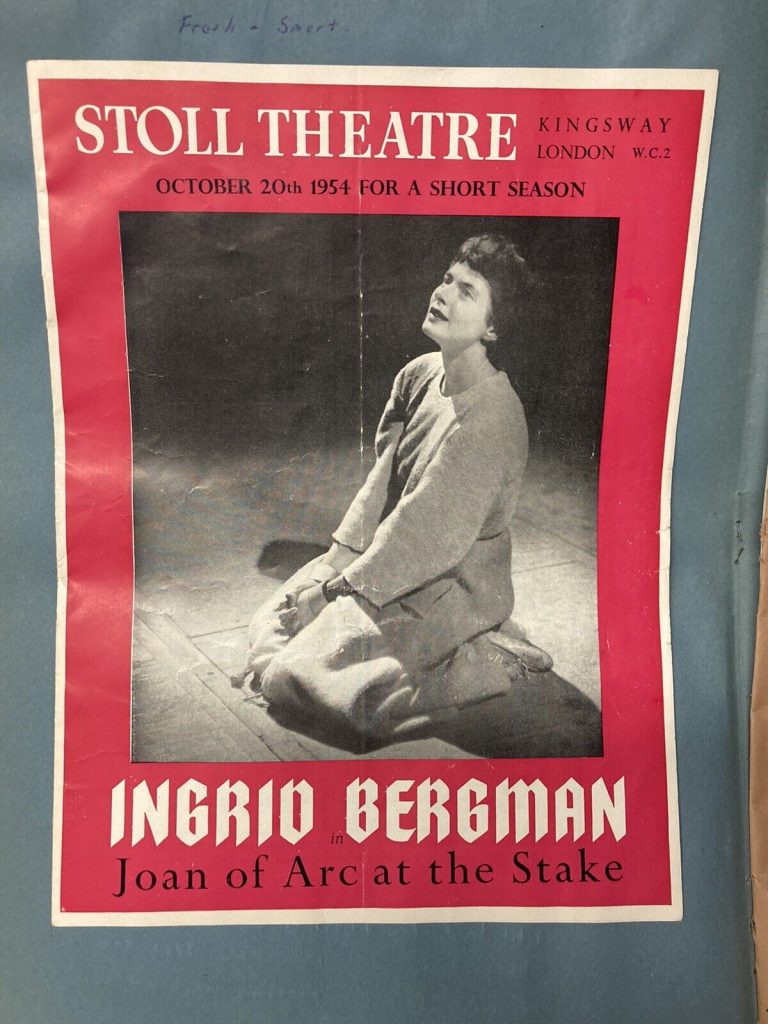

Though her marriage to Mr. Rossellini fell apart less than two years later, she won custody of their three children Robertino, Isabella and Ingrid ; she never changed her attitude. And Miss Bergman continued to defend the films she made for him, though all were financial failures and received poor reviews in this country. The Rossellini debacles created a myth that before she worked for him she had only successes. Among her pre-Rossellini failures were ”Arch of Triumph,” ”Joan of Arc” and ”Under Capricorn,” all of which came immediately before she went to work for Mr. Rossellini.

It was Miss Bergman’s lifelong desire for artistic growth that drew her to Mr. Rossellini. She had been deeply moved by his films ”Open City” and ”Paisan,” which established him as a major force in neorealism. Money had never been enough for Miss Bergman. ”You don’t act for money,” she said. ”You do it because you love it, because you must.”

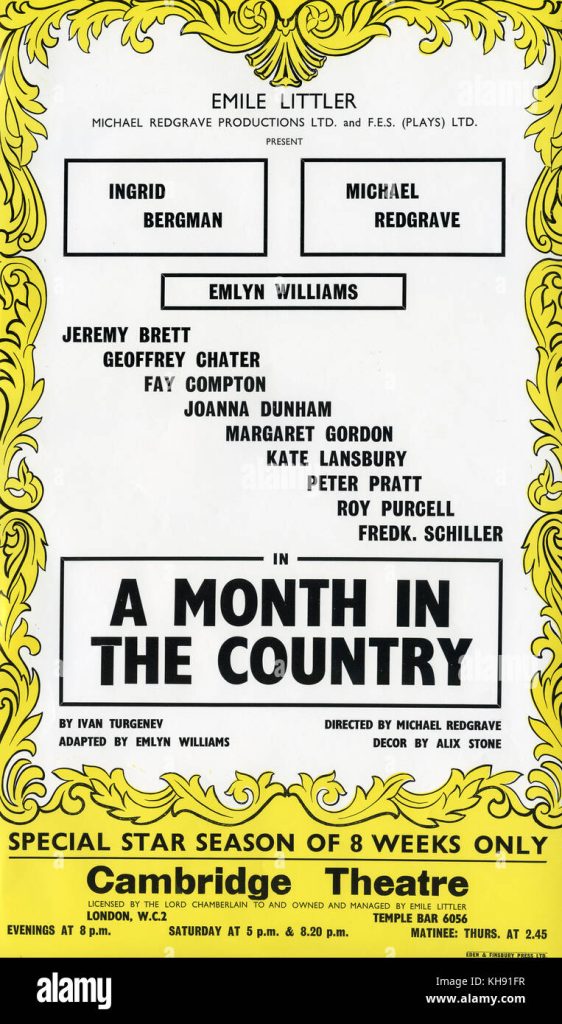

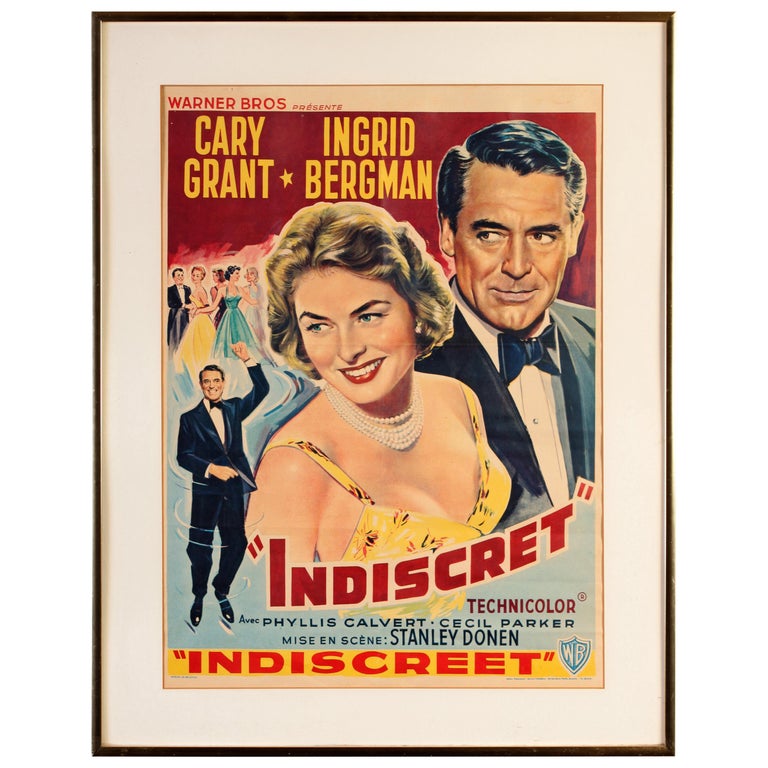

Even the Oscars she had won were not enough. On Broadway, her portrayal of Joan of Arc, in Maxwell Anderson’s ”Joan of Lorraine,” won her an Antoinette Perry award, the highest honor in the American theater. Audiences and critics could adore her love scenes with Humphrey Bogart in ”Casablanca” and with Cary Grant in ”Notorious.” But praise, too, was not enough.

”There is a kind of acting in the United States,” she said many years later, ”especially in the movies, where the personality remains the same in every part. I like changing as much as possible.”

This artistic need prompted her to write to Mr. Rossellini: ”I would make any sacrifice to appear in a film under your direction.” He leaped at the opportunity, rewrote a script he had intended for Anna Magnani, and went with Miss Bergman to the Italian island of Stromboli to make the film of that name.

While this movie was being made, she asked her husband for a divorce so she could marry Mr. Rossellini. He tried to block it, even after learning she was pregnant with the director’s child.

The first of her three children with the director was born, under a media siege, in Italy, seven days before she was remarried. Dr. Lindstrom, a neurosurgeon, won custody of their daughter, Pia, who subsequently became a well-known television reporter.

By 1957, she and Mr. Rossellini were separated, but before that Miss Bergman had begun a new phase in her career. She made ”Anastasia” for 20th Century-Fox and won her second Oscar in 1956, playing the mysterious woman who might or might not be the surviving daughter of Czar Nicholas II. She then won a television Emmy award for her performance of the tormented governess in a dramatization of Henry James’s ”The Turn of the Screw.” In 1958 she married Lars Schmidt, a successful Swedish theatrical producer.

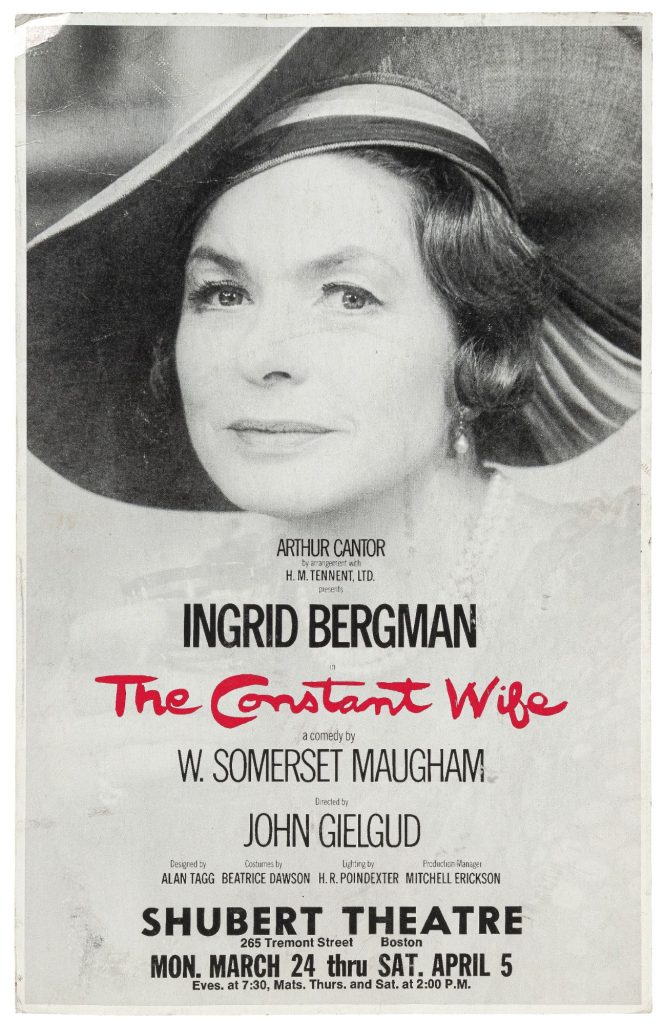

Miss Bergman refused to be drawn into arguments about acting in movies, the theater and television. She enjoyed all three. In the movies, she said, one acted for one eye, the camera. In the theater, for a thousand eyes, the theater audience. Television was ”wonderful,” she said, allowing for the frenzied schedule.

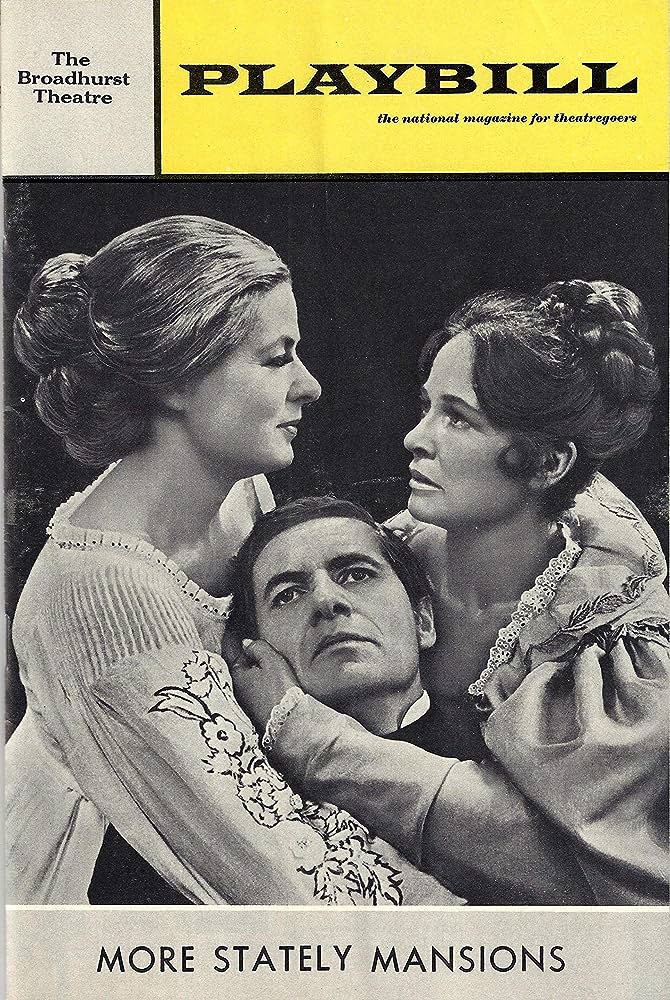

Maturity strengthened her determination to be more selective in roles. This was one of the main reasons she returned to Broadway in 1967, after a 21-year absence, in the role of a mother disliked by her son in Eugene O’Neill’s ”More Stately Mansions.”

She had met the playwright in her Hollywood years, when, during a vacation from films, she played the prostitute in his ”Anna Christie” in theaters in New Jersey and on the West Coast. During another sabbatical from Hollywood, in 1940, she had made her Broadway stage debut as Julie in ”Liliom,” opposite Burgess Meredith.

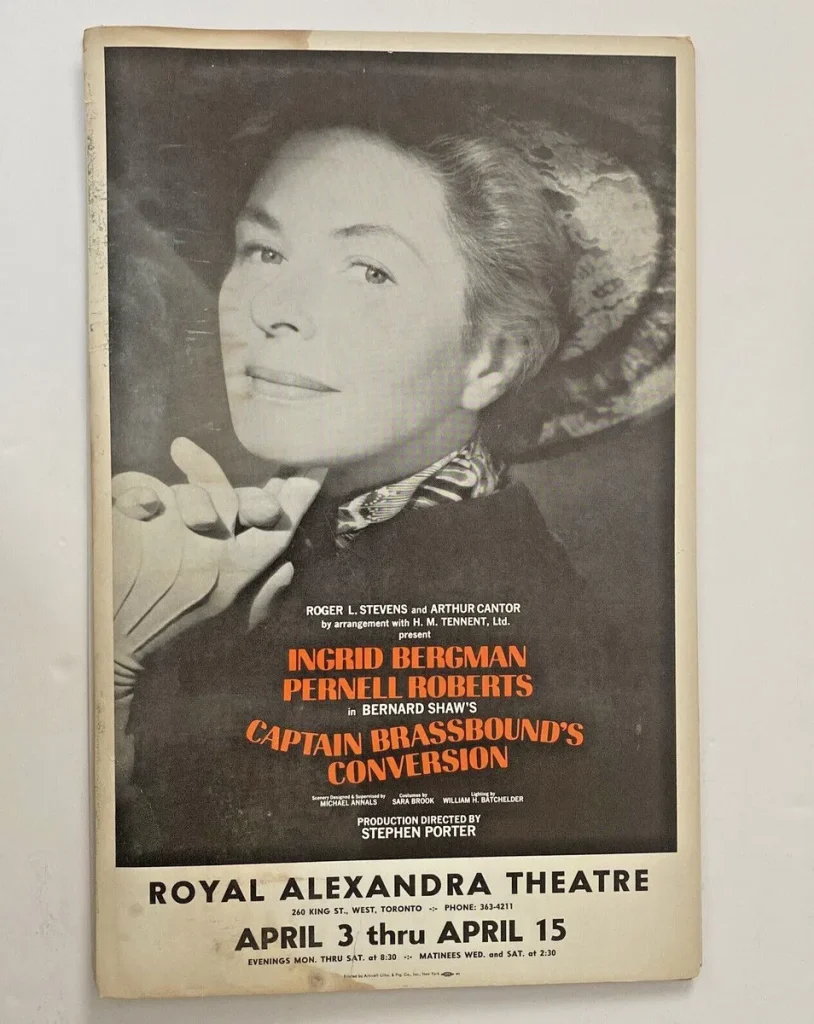

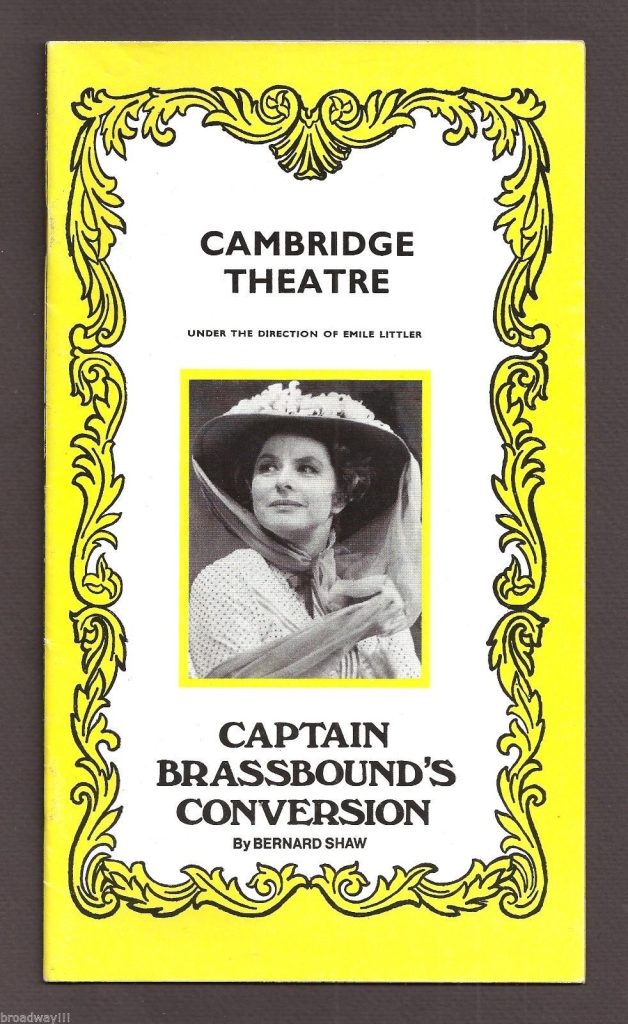

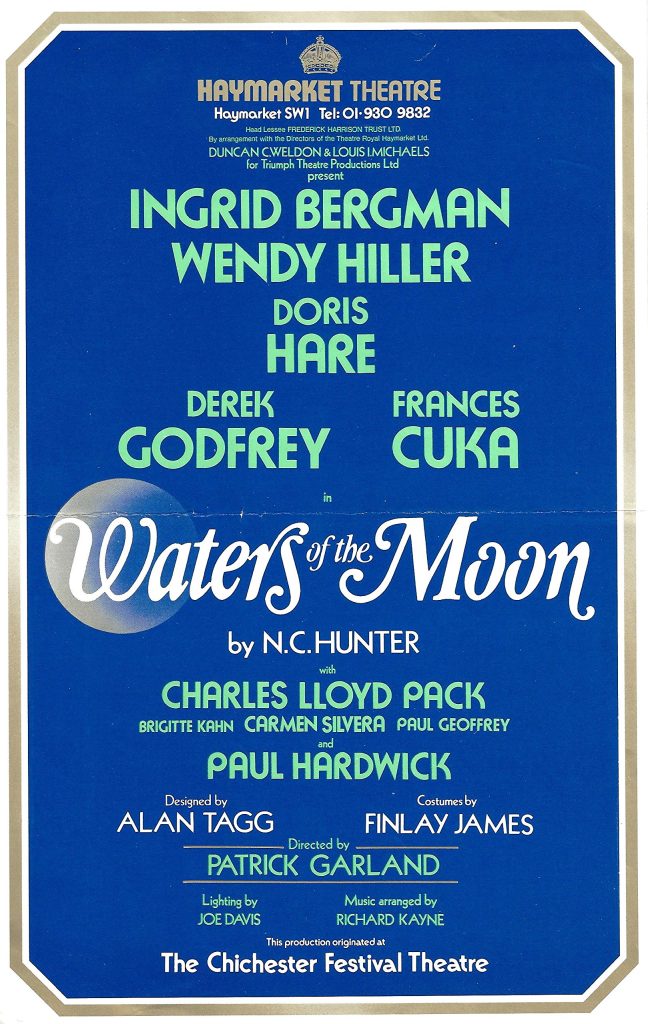

Miss Bergman’s next growth period, which included stage performances of works by George Bernard Shaw and Henrik Ibsen and the role of the vengeful millionaire in the film version of ”The Visit,” was climaxed by the fulfillment of a 13-year effort to persuade Ingmar Bergman, the director, to let her work for him.

In his ”Autumn Sonata,” she gave what she considered her finest performance, as a middle-aged concert pianist who, during a brief visit to her married daughter, played by Liv Ullmann, engages in prolonged and tearful confrontations that reveal a complex and searing love-hate relationship. She was nominated for her fourth Oscar for this 1978 movie, and she said it might be her last role.

”I don’t want to go down and play little parts,” she said. ”This should be the end.” Miss Bergman always refused to play any part that required her to be nude or seminude. Although she was opposed to movie censorship, she considered nudity, particularly in love scenes, ugly, saying: ”Since the beginning of time, good theater has existed without nudity. Why change now?”

Miss Bergman was born in Stockholm on Aug. 29, 1915. Her mother, who was from Hamburg, Germany, died when Ingrid was three years old. As an only child, she learned to create imaginary friends. Her father, who had a camera shop, adored her and photographed her constantly, often in costume. He died when she was 13. She lived briefly with an unmarried aunt and then with an uncle and aunt who had five children.

At 17, although she was tall and somewhat ungainly – she was 5 feet 9 inches and weighed about 135 pounds – she auditioned successfully for the government-sponsored Royal Dramatic School.

Within seven years she was one of the leading movie stars in Sweden and had refused several offers from Hollywood. Finally, in 1939, at the age of 24, Miss Bergman agreed to do a film for David O. Selznick. It was ”Intermezzo,” with Leslie Howard. She returned to Sweden to her husband, who was then a dentist, and their daughter, Pia.

The film was so successful that Mr. Selznick, convinced he had found ”another Garbo,” persuaded her to return to Hollywood. Looking back on her career many years later, particularly on her feeling of youthful shyness and awkwardness, the actress said: ”I can do everything with ease on the stage, whereas in real life I feel too big and clumsy. So I didn’t choose acting. It chose me.” Miss Bergman is survived by her four children, who were reported to be flying to London yesterday for the funeral. The funeral will be ”a very quiet, family affair,” said Alfred Jackman, funeral director at Harrods, the London department store that is handling the arrangements. Mr. Jackman added, ”After cremation, her ashes may be taken back to Sweden.”