TCM overview:

Bette Midler built a successful stage, screen and recording career on the basis of her self-styled “Divine Miss M” character – a sassy, hip-wagging classic “broad” archetype. She was quick with the comebacks, took no guff and had a tendency to burst into tunes from the Great American Songbook. Her initial stage fame and string of nostalgia-tinged hit albums in the 1970s eventually led to big screen success, with dramas like the pseudo Janis Joplin biopic “The Rose” (1980) and three-hankie chick flick “Beaches” (1990). She also lent appropriately outrageous variations of Miss M to comedies including “Ruthless People” (1986), “Down and Out in Beverly Hills” (1986) and “The First Wives Club” (1996). In an era where stage, screen and recording crossover success was rare, only Liza Minnelli rivaled Midler when it came to endless concert tour schedules and triumph in all genres. More than 30 years into her career, the entertainer was still scoring hits with such albums as 1998’s Bathhouse Betty and the televised special of her acclaimed Caesar’s Palace act “Bette Midler: The Showgirl Must Go On” (HBO, 2010). As a film star, live performer and winner of Grammy, Emmy and Golden Globe awards, Midler was an entertainment icon of the highest order.

The Divine Miss M was born on Dec. 1, 1945 to a seamstress mother and housepainter father from Paterson, NJ. The couple had moved to Hawaii just prior to Midler’s birth, where her father landed a job at a Navy yard. The transplanted Jewish East Coasters were a bit of an oddity in the rural South Pacific sugar cane fields, but Midler developed a quick wit to combat her outsider status, winding up as a well-liked class clown and notorious performer. Along with two other girls, she formed a vocal trio that played school events and eventually began to book gigs entertaining at adult venues. As soon as the senior class president and valedictorian accepted her diploma in 1963, she headed right into the entertainment field, putting in a year in the Drama Department at the University of Hawaii before landing a small role in the film adaptation of James Michener’s “Hawaii” (1966).

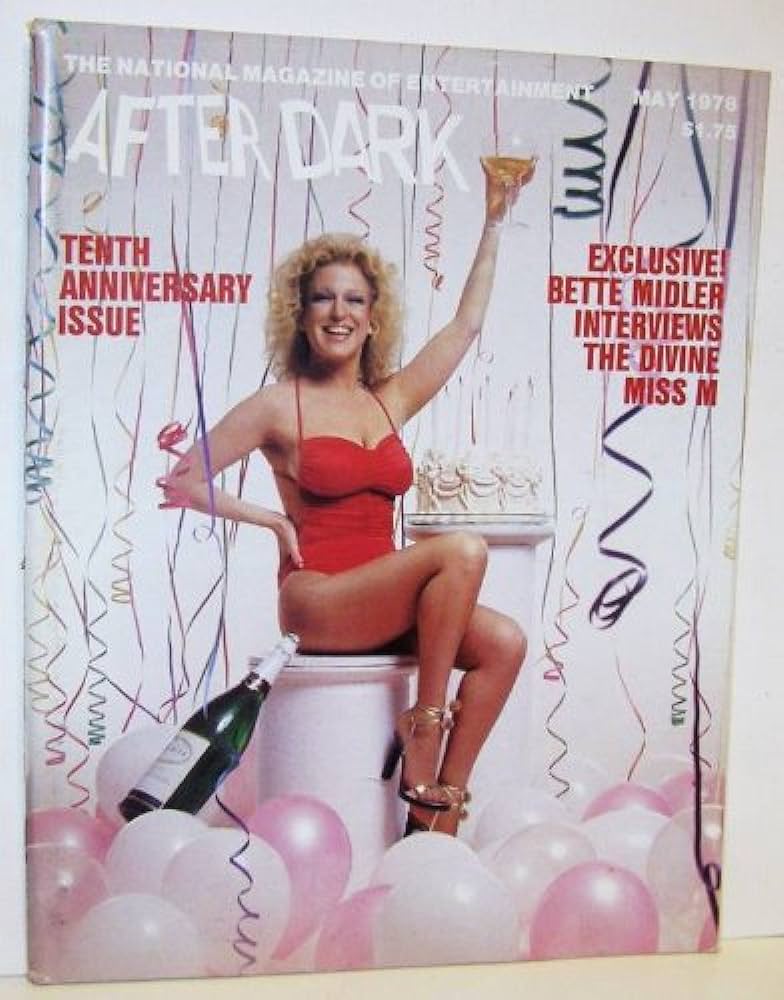

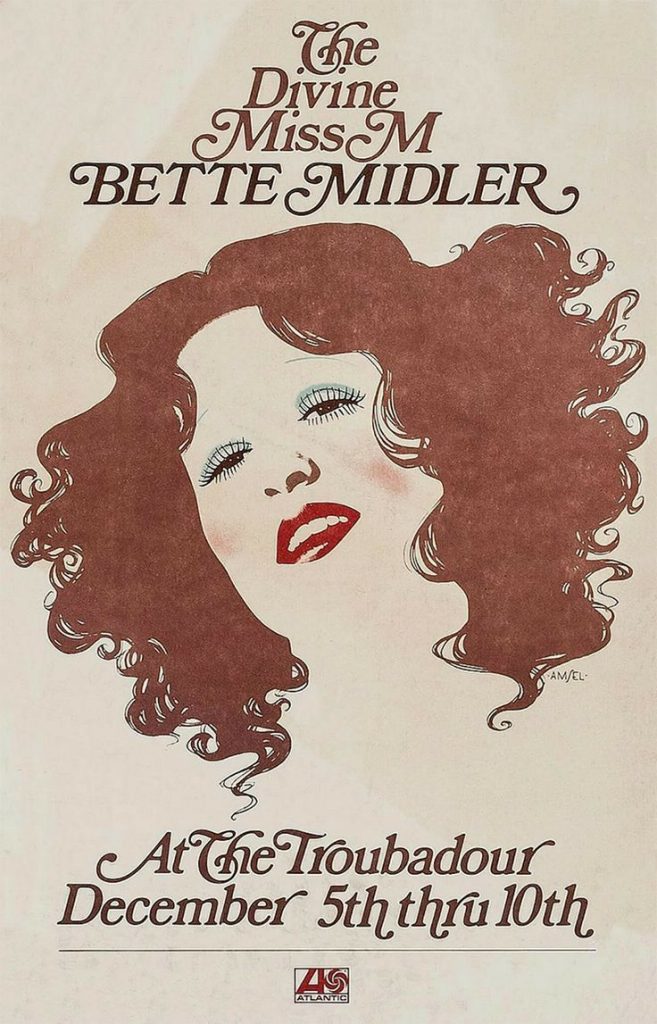

Midler spent her first big paycheck on a move to New York City, where, after a short stint as a go-go dancer, she went to an open call for a national tour of “Fiddler on the Roof” and ended up in the Broadway cast, taking over the part of Tzeitel in February 1967 and staying with the role for three years. After a run as The Acid Queen in a Seattle Opera Association production of “Tommy,” Midler returned to New York, determined to focus on her singing career. After rave club reviews which took note of her powerful pipes, she was booked on all the top variety TV shows of the day. She took a 16-week engagement that electrified the towel-clad gay clientele of the Continental Baths, where Barry Manilow backed her on piano. It was at that time that the larger-than-life persona of ‘The Divine Miss M’ – and along with it, a loyal gay following – was born.

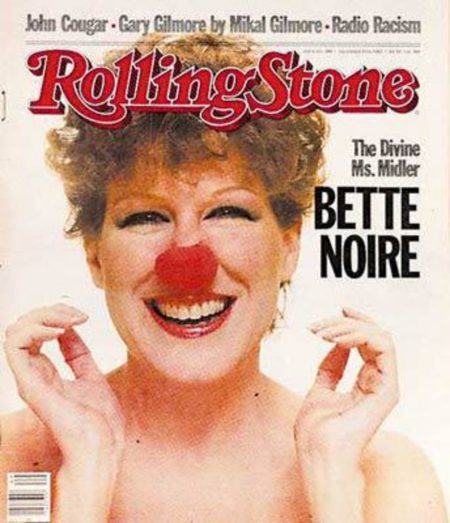

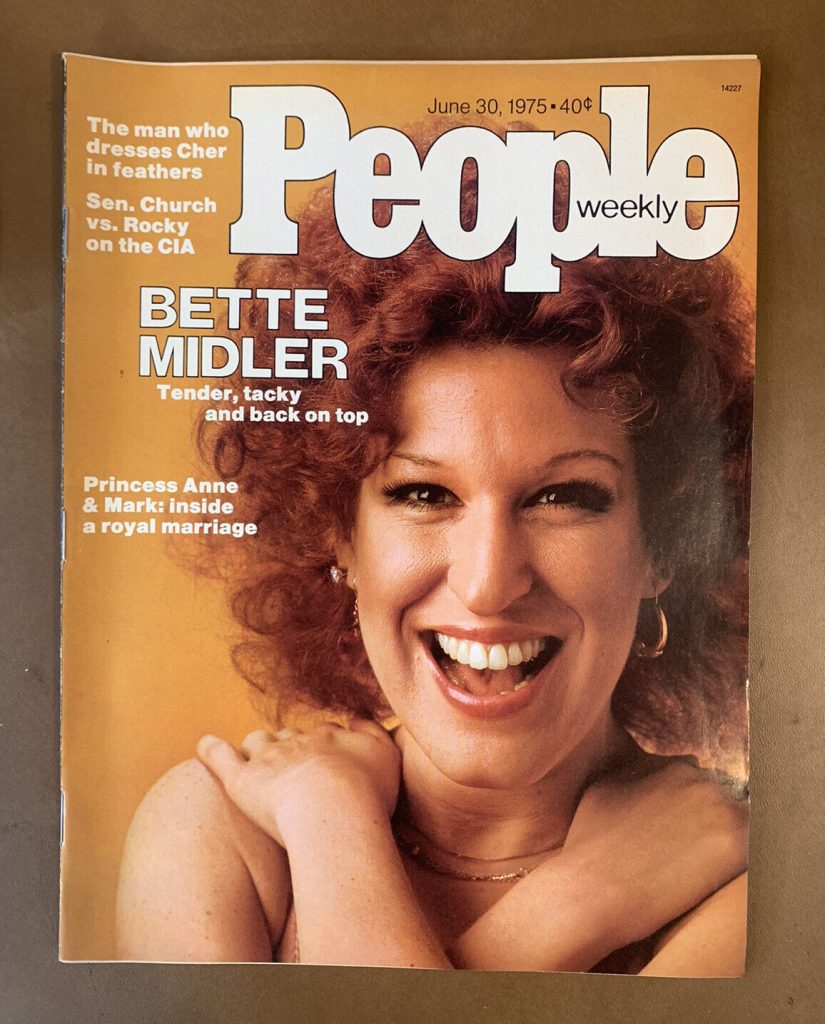

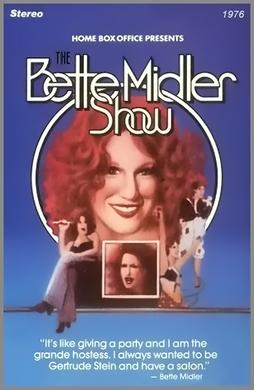

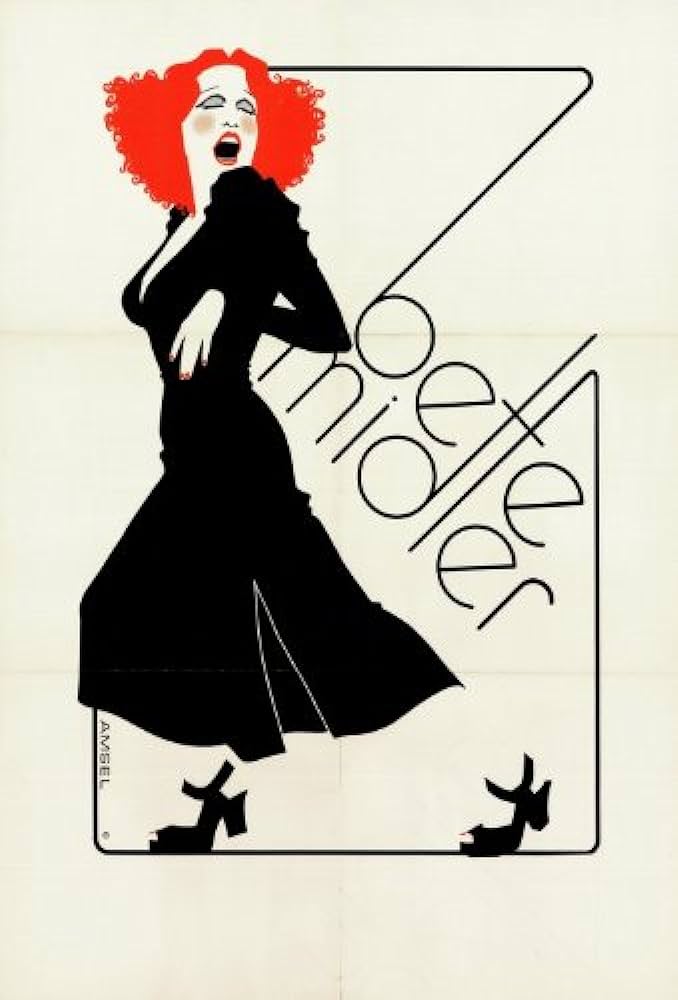

Atlantic Records signed Midler to a record deal and released her debut album, The Divine Miss M, in 1972. The bawdy, red-haired performer with the wide, toothy smile built her career on being outrageous, but also balanced the camp by interspersing a few tears for the human spirit amidst the sequins and fringes. Musically, her early work “nailed the nostalgia thing” with Andrews Sisters takeoffs – i.e. “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” – and 1960s girl group numbers, as well as including blues and show tunes in her broad musical spectrum. The album went gold and won her the Grammy for Best New Artist. Midler developed a larger version of her earlier cabaret revue and performed “Clams on the Halfshell” at the Palace Theater, earning a Special Tony Award in 1974. On a complete roll, she spent the next three years on national and international concert tours, wowing the gays and the straights who poured in to worship Ms. Divine.

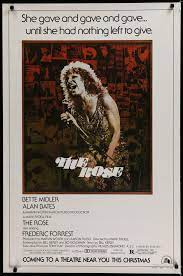

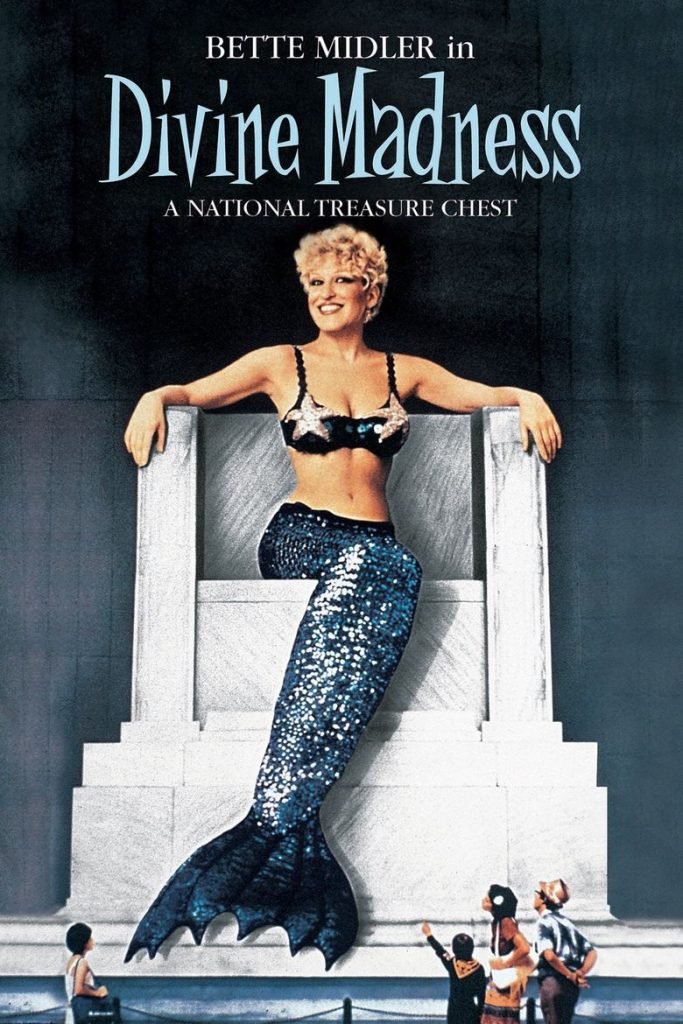

Unfortunately, sales dropped off sharply for her third LP, Songs for the New Depression (1976), but she retained a loyal concert following and picked up her first Emmy as the star of “Bette Midler: Ol’ Red Hair Is Back” (NBC, 1977). She made her first impact as a film actress in Mark Rydell’s “The Rose” (1978), earning a Best Actress Oscar nomination for her portrayal of a high-strung, burned-out singer loosely based on Janis Joplin. The soundtrack LP went platinum in 1980, aided by the Top Ten title song which became a bona fide smash single. A Midler concert film and soundtrack entitled “Divine Madness” came out later that year, as did her first book, A View from a Broad, a humorous memoir of her first world tour. Midler was at the top of her game, but bad advice from her agent led her to take a screen role in the aptly named comedy “Jinxed!” (1982). She suffered greatly, warring with co-star Ken Wahl and director Don Siegel and ultimately serving as scapegoat when the picture flopped. The film’s failure followed her firing of her back-up singers the Harlettes, who successfully sued and later won a $2 million judgment. The twin debacles helped bring on a nervous breakdown, which kept her off the screen for four years, though she remained busy with concert work and TV specials.

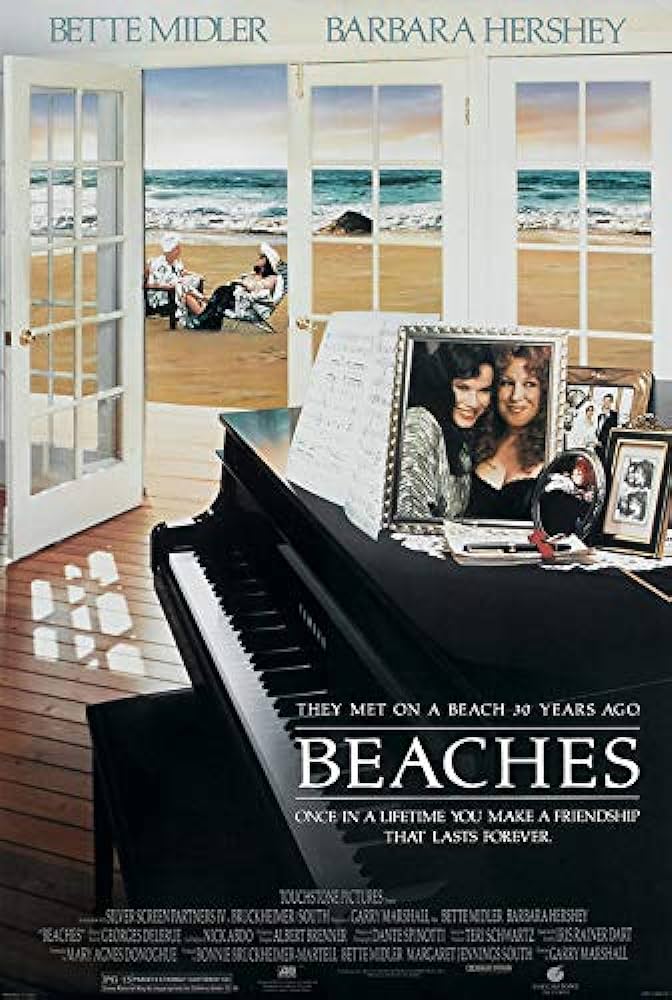

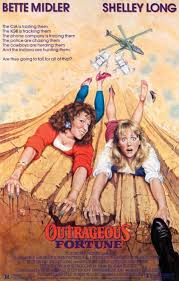

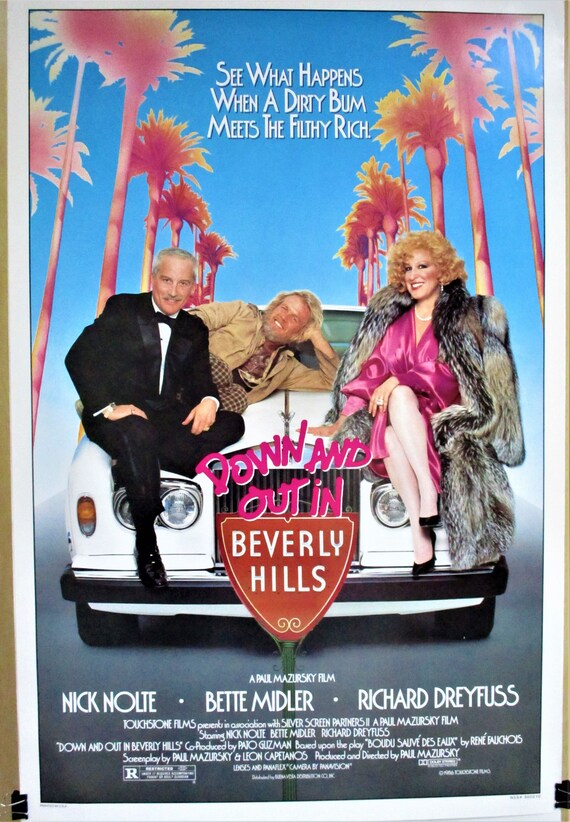

Midler bounced back with a formidable focus on big screen comedies throughout the 1980s. Signed by Disney in 1986, she proved herself a deft, aggressive comedienne in a skein of profitable films, beginning with the bright satire “Down and Out in Beverly Hills” (1986) and continuing through the enjoyable if forgettable “Outrageous Fortune” (1987) and “Big Business” (1988), in which she and Lily Tomlin each played identical twins. Probably the best of her movies during this period was the clever black comedy “Ruthless People” (1986), which hilariously paired her with Danny DeVito as a thoroughly despicable couple. She formed her own production company, All Girl Productions, and made her first foray into producing with the moderately successful “Beaches” (1988), co-starring alongside Barbara Hershey as a charismatic New York cabaret performer in a tale of the lifelong bond between girlfriends. Bette also performed the film’s theme, “The Wind Beneath My Wings,” which became her first No. 1 hit, won a Grammy, and along with “The Rose,” became one of her two definitive numbers.

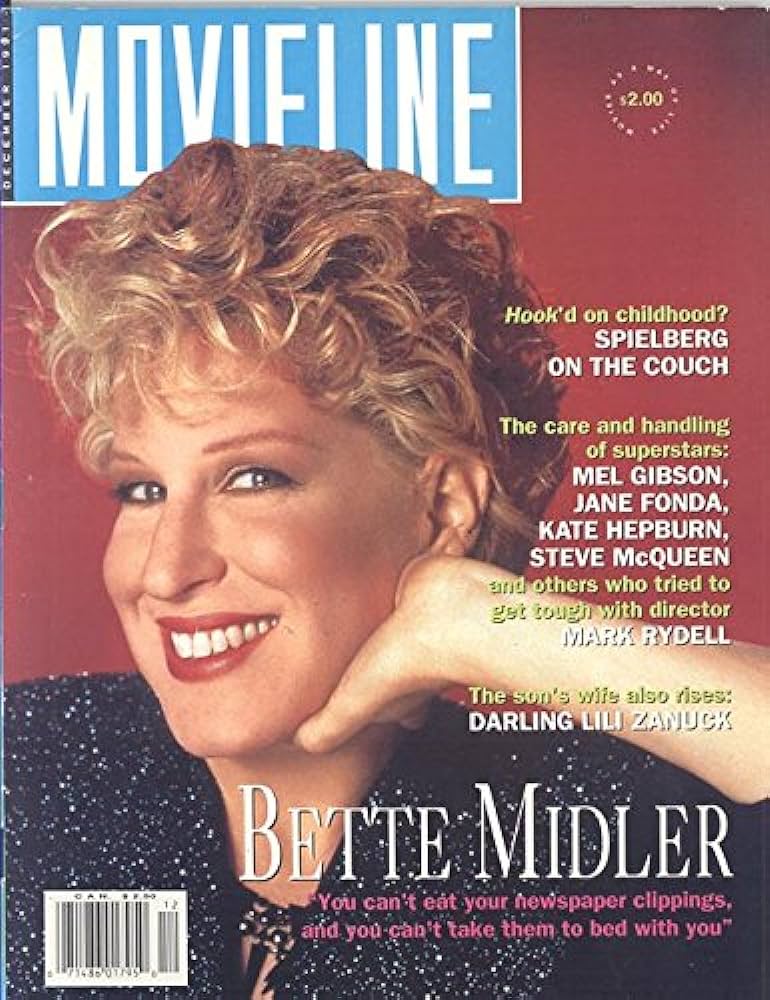

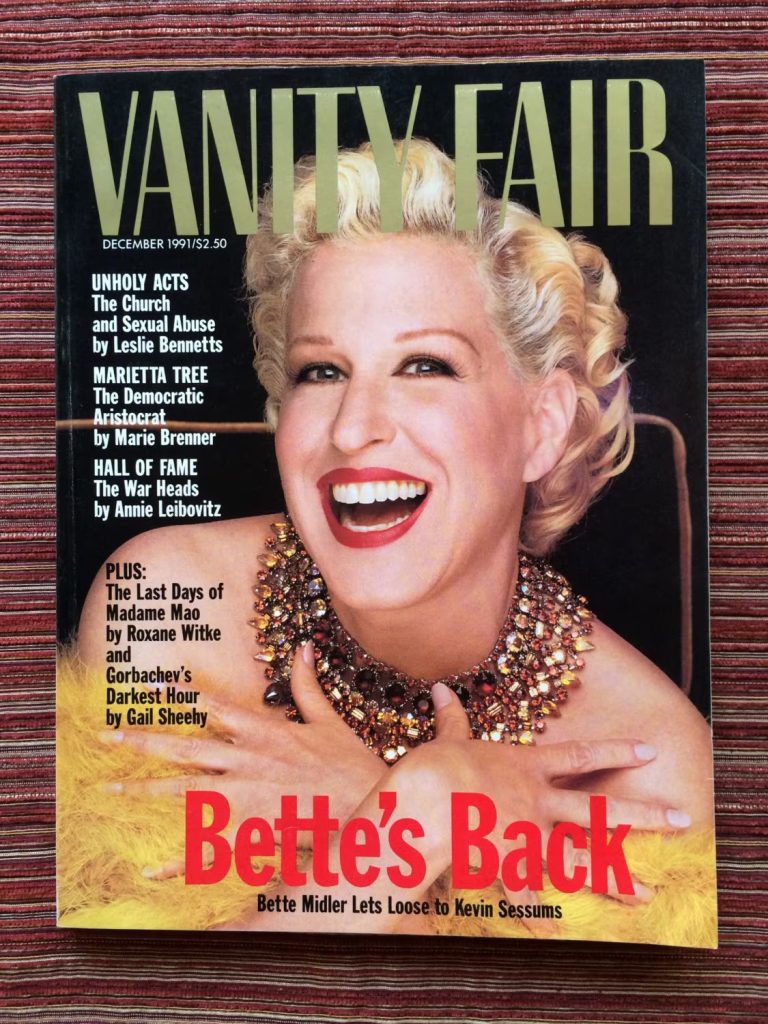

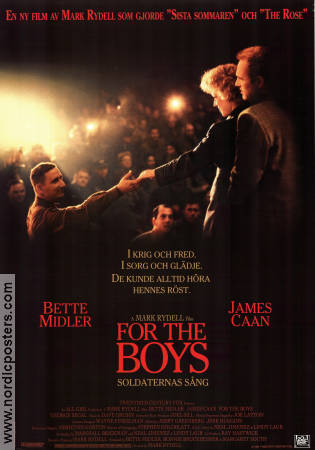

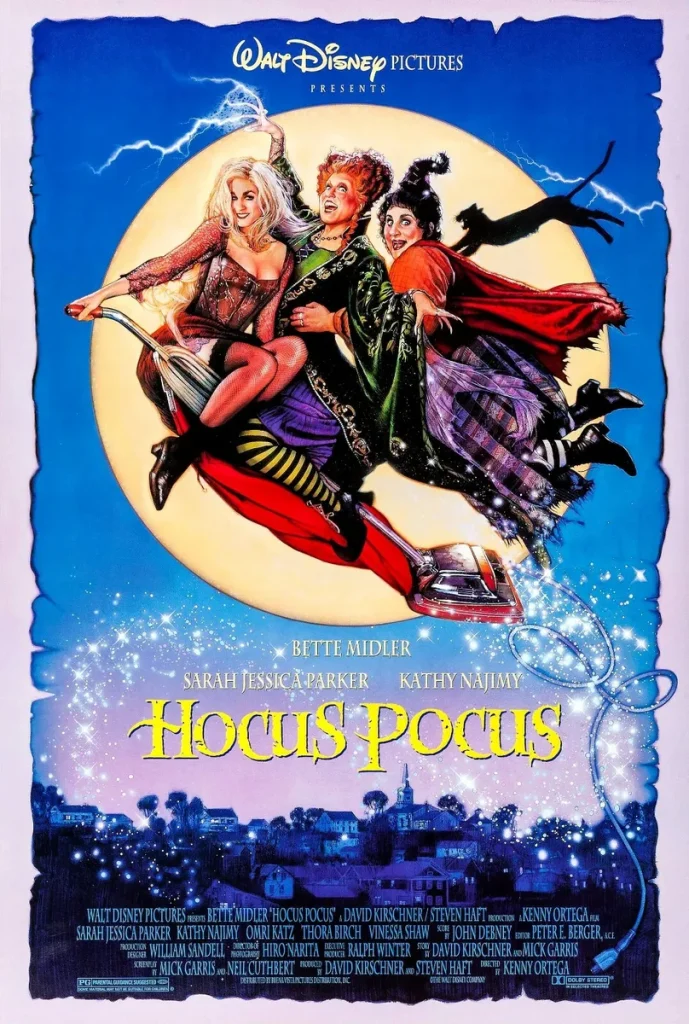

The studio, sensing it was on to something, cast her in two old-fashioned follow-up tearjerkers, but Jeffery Katzenberg’s wrong-headed passion for “Stella” (1990) earned Premiere magazine’s kiss of death: “A must to avoid.” She fared somewhat better in Rydell’s “For the Boys” (1992) as a World War II USO performer, a seemingly natural fit for Midler, based on her earlier success with the Andrews Sisters’ material. The picture revealed a flair for drama not really tapped since “The Rose” and earned Midler a second Best Actress Oscar nomination and a Golden Globe win, but audiences avoided the big-budget musical like the plague. She next teamed with Woody Allen to portray a married couple for Paul Mazursky’s “Scenes from a Mall” (1991), but it did not come close to Midler’s earlier comedic success. Her outlandish appearance as a long-deceased witch in Disney’s “Hocus Pocus” (1993), suggesting a return to the zany fare that made Midler a bankable movie star seven years earlier, could not save the ghoulish, effects-laden bomb that was deemed a discredit to Disney “family entertainment” by film critic Leonard Maltin.

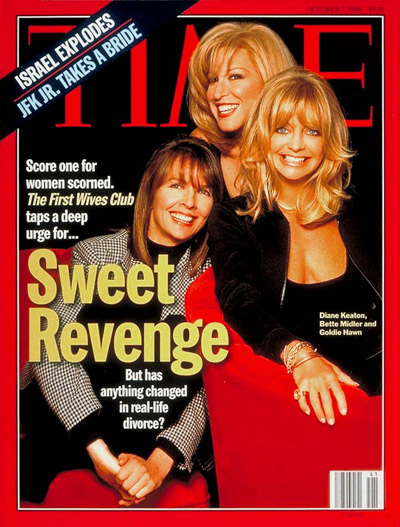

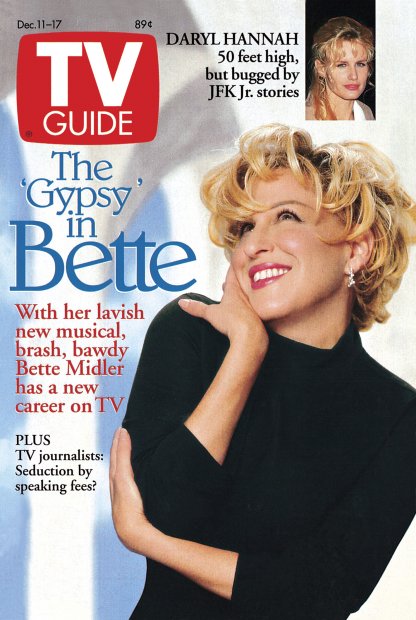

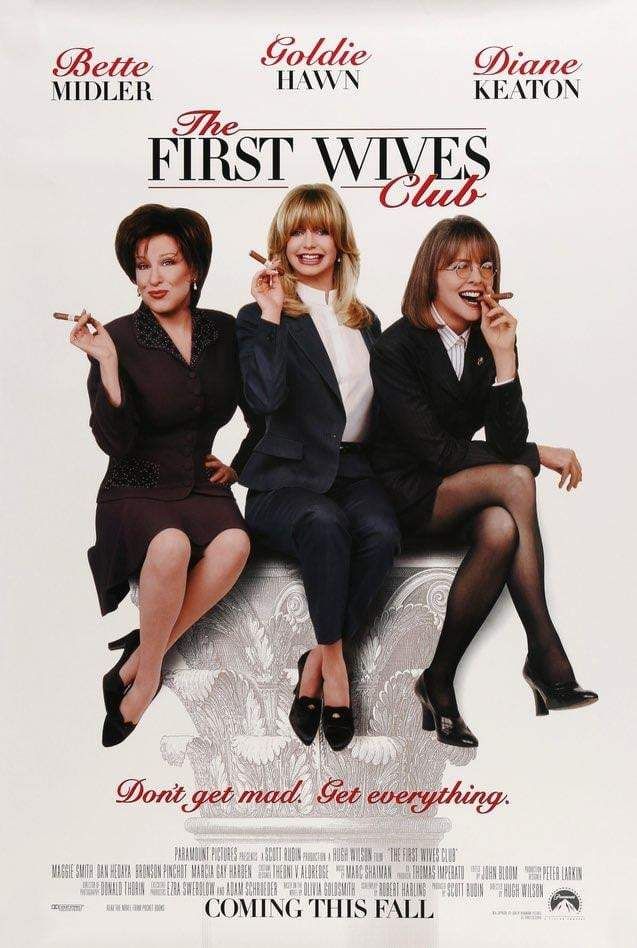

The year 1993 marked Midler’s overdue return to live concert performances with “Experience the Divine,” which was capped by a record-breaking 30-night stand at New York’s Radio City Music Hall. That same year, she gave a tour-de-force performance as Mama Rose in a TV remake of the musical classic “Gypsy” (CBS), which earned her a second Golden Globe Award. Midler returned to big screen comedy full-force when teaming with Diane Keaton and Goldie Hawn in Hugh Wilson’s “The First Wives’ Club” (1996), a film about women whose husbands have left them for younger beauties which – thanks to the collective star power of the threesome – became one of the surprise hits of the season. She also starred with Dennis Farina in “That Old Feeling” (1997), about a divorced couple whose romantic yearnings are rekindled at their daughter’s wedding, as well as returned to the mic to earn an Emmy for “Bette Midler – Diva Las Vegas” (HBO, 1997). She garnered another Emmy nomination for her guest turn as a secretary in the final episode of the long-running CBS series “Murphy Brown” (CBS, 1988-1998) in 1998, before kicking off the international “Divine Miss Millennium” tour the following year, welcoming in 2000 with a New Year’s Eve performance at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas.

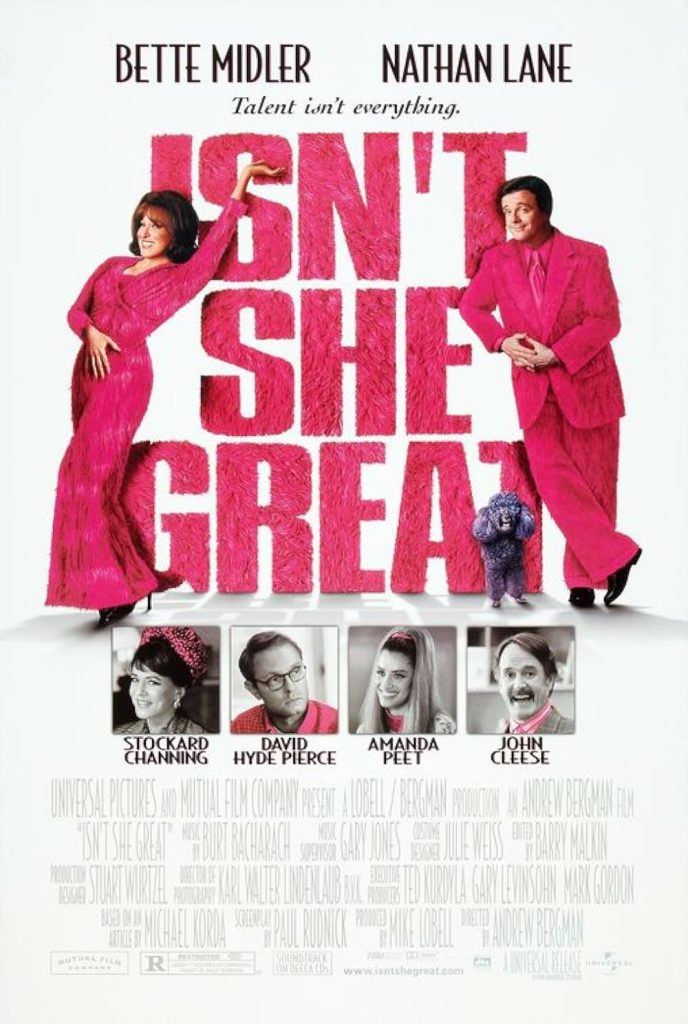

After a pair of box office failures with the Jacqueline Susann biopic “Isn’t She Great?” (2000) and the pallid comedy “Drowning Mona” (2000), Midler agreed to headline a sitcom in an effort to revive her acting career. In “Bette” (CBS, 2000-01), she played a variation of herself – a showbiz veteran juggling the demands of career, marriage and motherhood. Despite initially positive reviews, ratings were so-so and negative gossip about behind-the-scenes problems plagued the series’ image. After dabbling in the executive producer role when she helped bring “The Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood” (2002) to the big screen, Midler reunited with former collaborator Barry Manilow to record Bette Midler Sings the Rosemary Clooney Songbook for Columbia Records. The album was a bit of a surprise hit and went gold, in addition to earning the pair a Grammy nod.

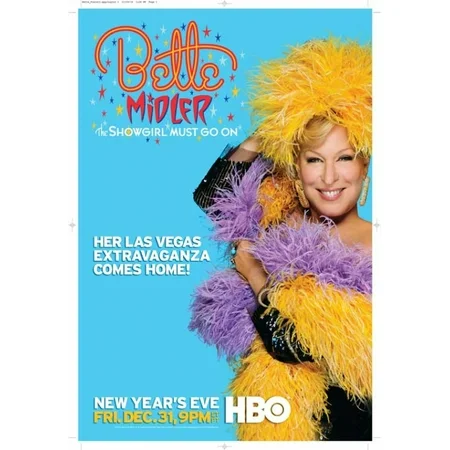

Midler spent the following year-plus back on the road with her “Kiss My Brass” concert tour and made a return to theaters in 2004 with her role as Bobbie Markowitz, a Jewish writer and recovering alcoholic in the remake of the cult classic “The Stepford Wives.” Midler and Manilow recreated their previous album success with 2005’s Bette Midler Sings the Peggy Lee Songbook and Midler returned to the studio in 2006 to record Cool Yule, a Grammy-nominated album of pop holiday classics. Helen Hunt lured Midler back to the big screen to star as her biological mother in Hunt’s pet project, the comedic drama “Then She Found Me” (2008). That same year, the 62-year-old powerhouse began a two-year run of “Bette Midler: The Showgirl Must Go On” at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas.

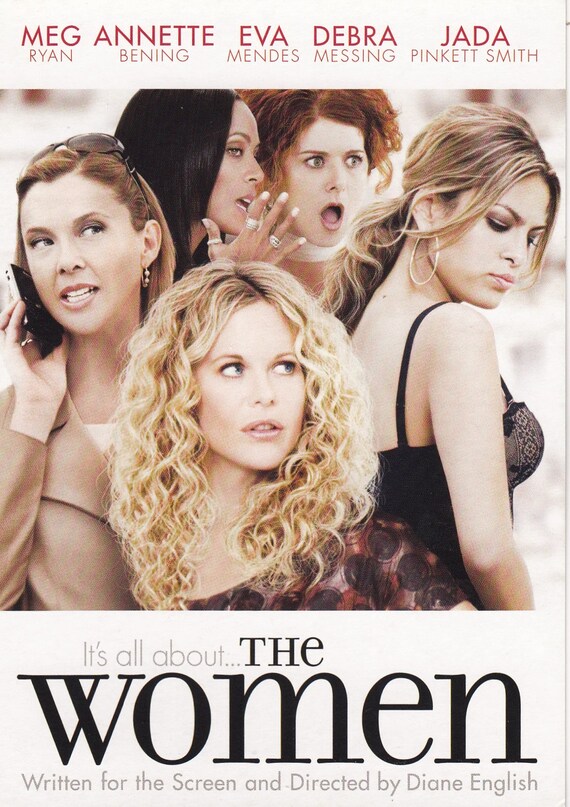

Midler appeared in theaters for a second time that year in an updating of George Cukor’s 1950s melodrama “The Women” (2008) co-starring with Meg Ryan, Annette Bening and Eva Mendes. Unfortunately, despite the star power of its all-female cast, the reinvention of “The Women” did little to improve upon the original and quickly disappeared from screens. Midler took part in a far more successful, if artistically less ambitious project two years later when she voiced the eponymous feline super villain in the family action-comedy “Cats & Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore” (2010). Recognized for doing what she did best, “Bette Midler: The Showgirl Must Go On” (HBO, 2010) picked up an Emmy nomination the following year and the 2010 album Memories of You found Midler waxing nostalgic with a compilation of her lesser known standards. Beginning in 2011, Midler uncharacteristically stayed behinds the scenes as one of the producers on the Broadways production of the musical “Priscilla: Queen of the Desert” and went on to win the Sammy Cahn Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012.

By Susan Clarke

The above TCM overview can also be accessed on line here.