Dorothy Bromiley was born in 1930 in Manchester. In 1952 she, along with Joan Elan and Audrey Dalton won major parts in the movie”The Girls of Pleasure Island” which was made in Hollywood. Ms Bromiley did not stay in the U.S. but pursued her career in Britain. Among her other films are “It’s Great to be Young” with John Mills in 1956 and “The Servant” which was directed by her one time husband Joseph Losey. An interesting article on Dorothy Bromiley can be accessed here.

Dorothy Bromiley Phelan (born 18 September 1930) is a British former film, stage and television actress and authority on historic domestic needlework.

Born in Manchester, Lancashire, the only child of Frank Bromiley and Ada Winifred (née Thornton). Bromiley played a role in a Hollywood film before returning to the UK where, in 1954, she started work as assistant stage manager at the Central Library Theatre, Manchester; followed by a West End stage role in The Wooden Dish directed by the exiled US film and theatre director Joseph Losey(who became Bromiley’s husband from 1956 to 1963). They have a son by this relationship, the actor Joshua Losey. Since 1963 Bromiley has lived with the Dublin-born actor and writer Brian Phelan (who appeared in the 1965 film Four in the Morning), they have a daughter, Kate.

Bromiley attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

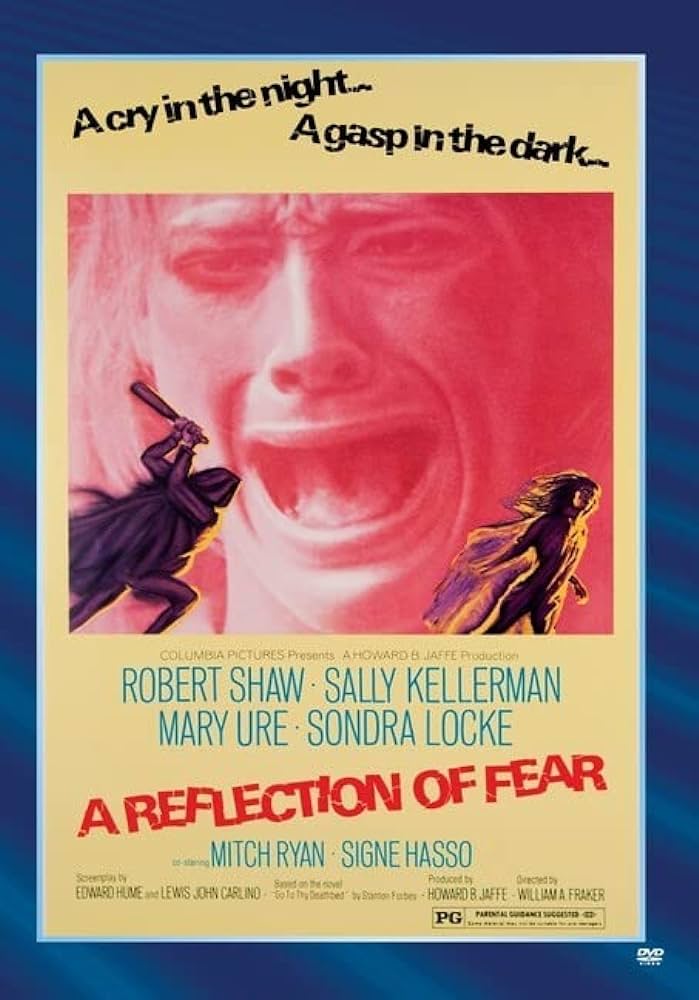

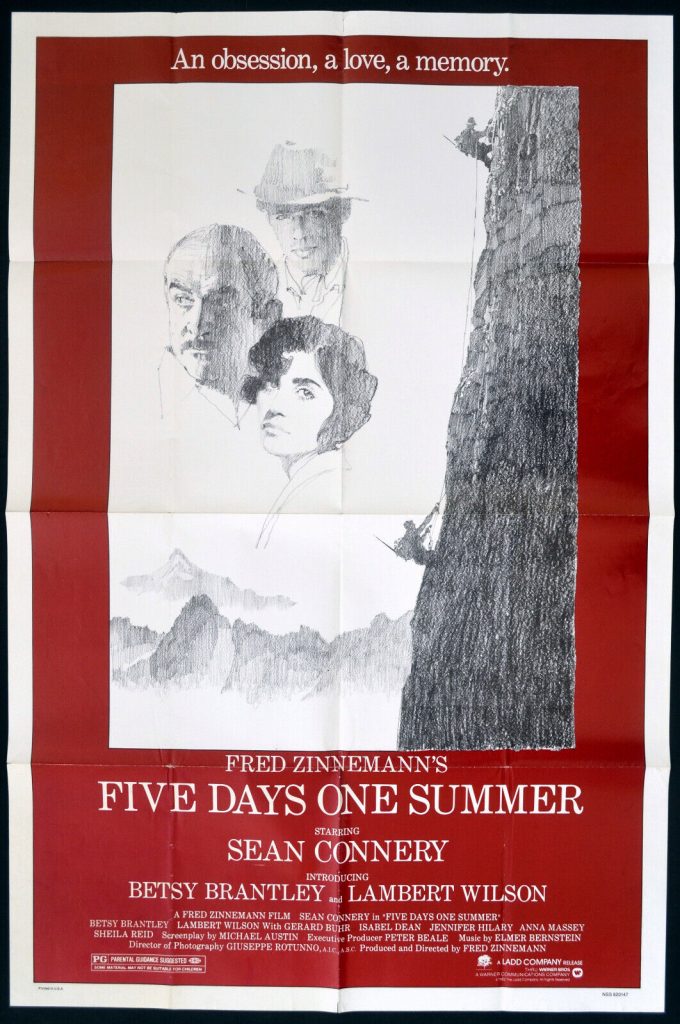

Bromiley successfully auditioned for the role of Gloria in the Hollywood film The Girls of Pleasure Island (Paramount, 1952). Her major roles in several British films include sixth former Paulette at Angel Hill Grammar School (aged 26 at the time) in It’s Great to Be Young (1956) in which Bromiley’s singing voice for the Paddy Roberts/ Lester Powell Ray Martin song “You are My First Love” was dubbed by Edna Savage (and by Ruby Murray in the pre-credits sequence), Rose in A Touch Of The Sun (1956) co-starring with Frankie Howerd, Sarah in Zoo Baby (1957) with Angela Baddeley, Small Hotel (1957), Angela in The Criminal (1960) and a minor role in The Servant (1963), the latter two directed by Losey.

Bromiley made her television drama debut as Pauline Kirby in “The Lady Asks For Help” (1956) an episode of Television Playhouse produced by Towers of London for ITV. This was followed by the role of Ann Fleming in “Heaven and Earth” (1957) part of the Douglas Fairbanks Presents series for ATV. Directed by Peter Brook, it also starred Paul Scofield and Richard Johnson, and was set on board a plane that develops engine trouble. Bromiley also had roles in such popular television series as The Adventures of Robin Hood (1956) as Lady Rowena (“Hubert” episode), Armchair Theatre (1957), Play of the Week (“Arsenic and Old Lace”) (1958), Saturday Playhouse (“The Shop at Sly Corner”) (1960), Z-Cars (1964), The Power Game (1966) and No Hiding Place (1965, 1966), and the television play Jemima and Johnny (1966). Her last television drama role was as Sarah Malory in Fathers and Families (BBC Television, 1977) directed by Christopher Morahan.

Dorothy Bromiley taught at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA) between 1966–72 and left to create The Common Stock Theatre Company, staging socially relevant theatre in colleges and non-traditional halls.

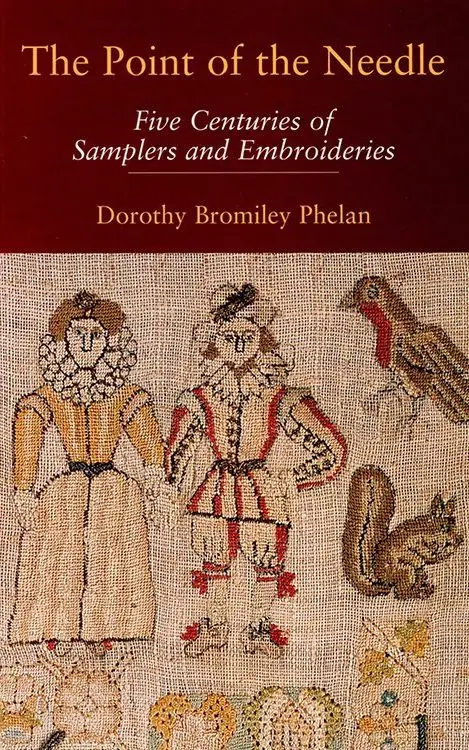

Retired from acting, Dorothy Bromiley lives in Dorset, and has developed an interest in 16th and 17th century amateur domestic needlework, writing on the subject, and curating two major exhibitions

The Telegraph obituary in 2024.

Dorothy Bromiley, who has died aged 93, was a Mancunian actress plucked from drama school to star in the Hollywood comedy The Girls of Pleasure Island (1953); she subsequently married the mercurial American director Joseph Losey, and later became a leading authority on the history of domestic needlework.

Dorothy Ann Bromiley was born in Levenshulme, Manchester, on September 18 1930. Her father, Frank, was a sports reporter and sometime designer of cotton bedspreads; her mother Ada, née Thornton, was a Court dressmaker.

Dorothy won a scholarship to Levenshulme High School and later moved to London to study at the Central School of Speech and Drama, then based at the Royal Albert Hall.

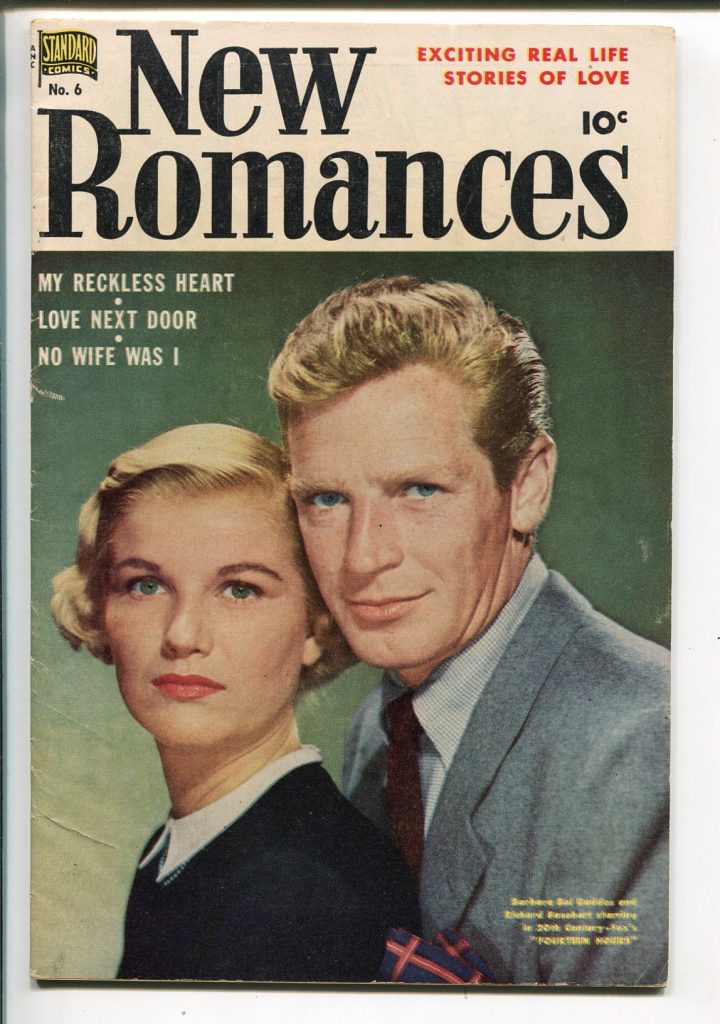

The extraordinary start to her career would have made for a Hollywood storyline in itself. In 1952, aged 21, she auditioned along with some 900 other young actresses for the American screenwriter and director F Hugh Herbert, who was looking for three “typical” English girls for his next film. The young student from Manchester fitted the bill, and Herbert invited her to give up her course and sign a contract with Paramount Studios.

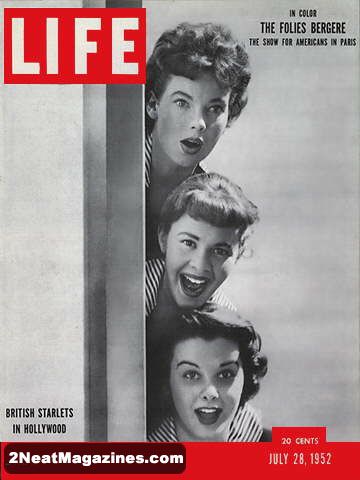

There was much US press interest in the arrival of Dorothy Bromiley and her fellow Brits, Audrey Dalton and Joan Elan. They made the cover of Life magazine in July 1952; inside, a photoshoot demonstrating the differences between English and American girls showed them drinking tea and dancing demurely.

A Paramount insider, asked to sum up the differing appeal of the girls, told the magazine: “The Bromiley dame is a pixie.” In The Girls of Pleasure Island, shot on the Paramount backlot, she played a 16-year-old, the youngest of three girls living with their uptight English father (Leo Genn) – the only man they have ever seen – on a largely uninhabited Pacific island. Romantic chaos ensues when 1,500 marines turn up to establish an aircraft base.

When the film was released in April 1953 the young stars visited 35 cities on a five-week publicity tour. Thereafter, however, Paramount, unable to find suitable roles for Dorothy Bromiley, left her idle.

Since her dream had always been to have a stage career, she happily returned to England in 1954. “I… went immediately to work as an assistant stage manager at the Central Library Theatre, Manchester, much to the disgust of my agents, MCA Ltd,” she recalled.

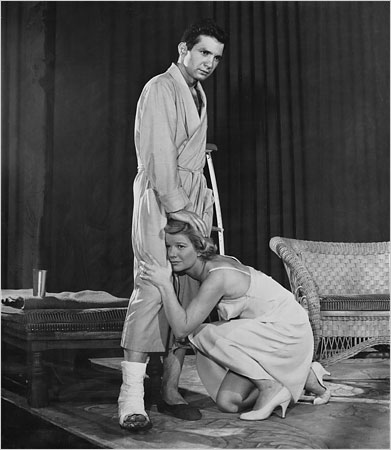

Within a few months, however, she secured a role in the West End in Edmund Morris’s The Wooden Dish; it marked the British stage-directing debut of Joseph Losey, who had been blackballed in Hollywood as a Communist.

She became his third wife in 1956. “The morning we were married, he gave me a ring and said, ‘For my child bride,’” she recalled. “I felt we had a Pygmalion and Galatea relationship.

Dorothy Bromiley’s youthful appearance saw her continue to be cast in juvenile roles. She was Wendy to Barbara Kelly’s Peter Pan in the 50th anniversary revival of JM Barrie’s play at the Scala Theatre, and played a rebellious sixth-former trying to save John Mills’s inspirational music teacher from the sack in the boisterous film It’s Great to Be Young (1956), written by Ted Willis.

She also played leading roles in the tepid comedies A Touch of the Sun (1956), with Frankie Howerd, and Zoo Baby (1957).

A juicy role she was offered in her husband’s melodrama The Gypsy and the Gentleman (1958) might have boosted her movie career, but she gave the part up when she became pregnant with their son, Joshua. Thereafter her only notable cinema role was a memorable cameo in Losey’s masterly chiller The Servant (1964), as a woman badgering Dirk Bogarde to vacate a telephone box.

By then she and Losey had divorced: “I think it was the most unselfish thing I’ve ever done, as I didn’t want the relationship to end,” she recalled. She always remembered him lovingly, although one of his lovers, Ruth Lipton, attested that “he spoke to her as if she was an idiot, [and] treated her… as a not very good servant.”

On television Dorothy Bromiley appeared in Z-Cars, The Power Game and No Hiding Place. From 1966 she was a teacher at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, and then in 1972 left to co-found the Common Stock Theatre Company, which brought “relevant theatre” to state-school teenagers and other non-traditional audiences. Enervated by battling with the Arts Council for funding, she retired to Dorset in 1976.

Having inherited a love of embroidery from her parents, in 1982 she found “my second calling” running a specialist needlework shop in Sherborne.

She went on to curate highly acclaimed needlework exhibitions for the Holburne Museum, Bath, in 2001, and the Dorset County Museum in 2003-04. The earliest exhibits included Elizabethan pillow covers and nightcaps, but one of her favourite pieces was a bucolic English scene embroidered by a Mrs Constance Dickinson on to linen cut from a pair of shorts while she was a PoW in Changi Prison.

Dorothy Bromiley’s books, which included The Point of the Needle (2001) and The Goodhart Samplers (2008), were published under the name Dorothy Bromiley Phelan. From 1963 her partner was the Irish actor and screenwriter Brian Phelan, although they never married.

She predeceased him by five days and is survived by their daughter, Kate, and her son.

Dorothy Bromiley, born September 18 1930, died May 3 2024