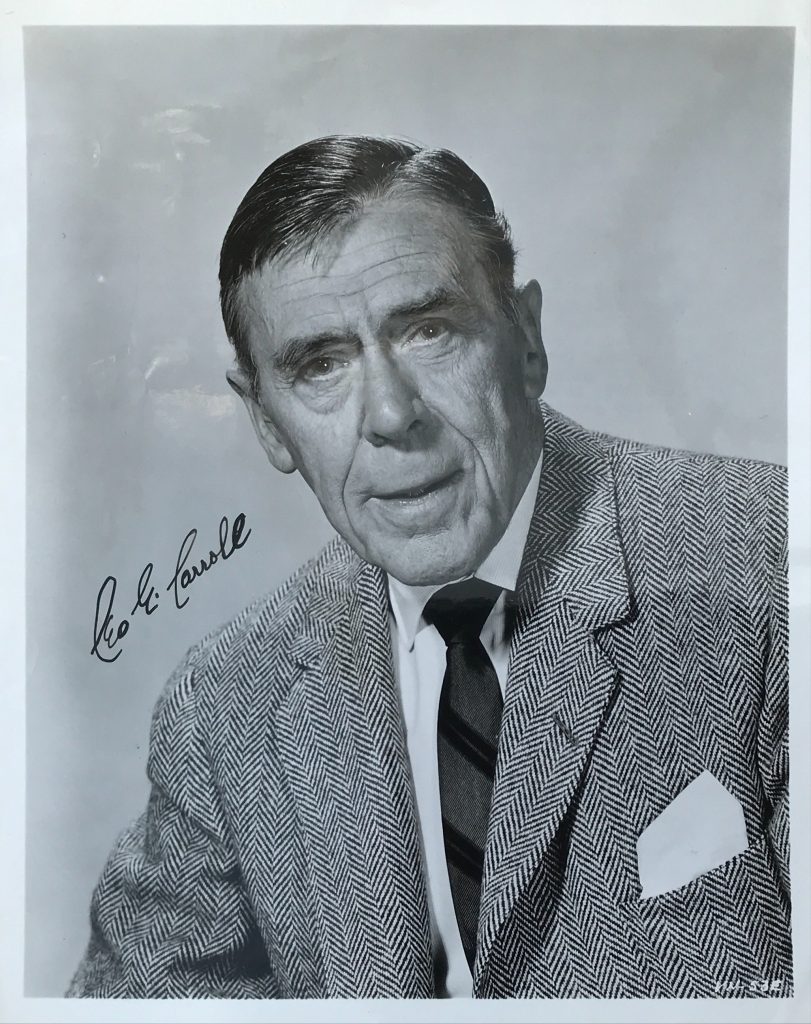

Ray Milland’s TCM profile:

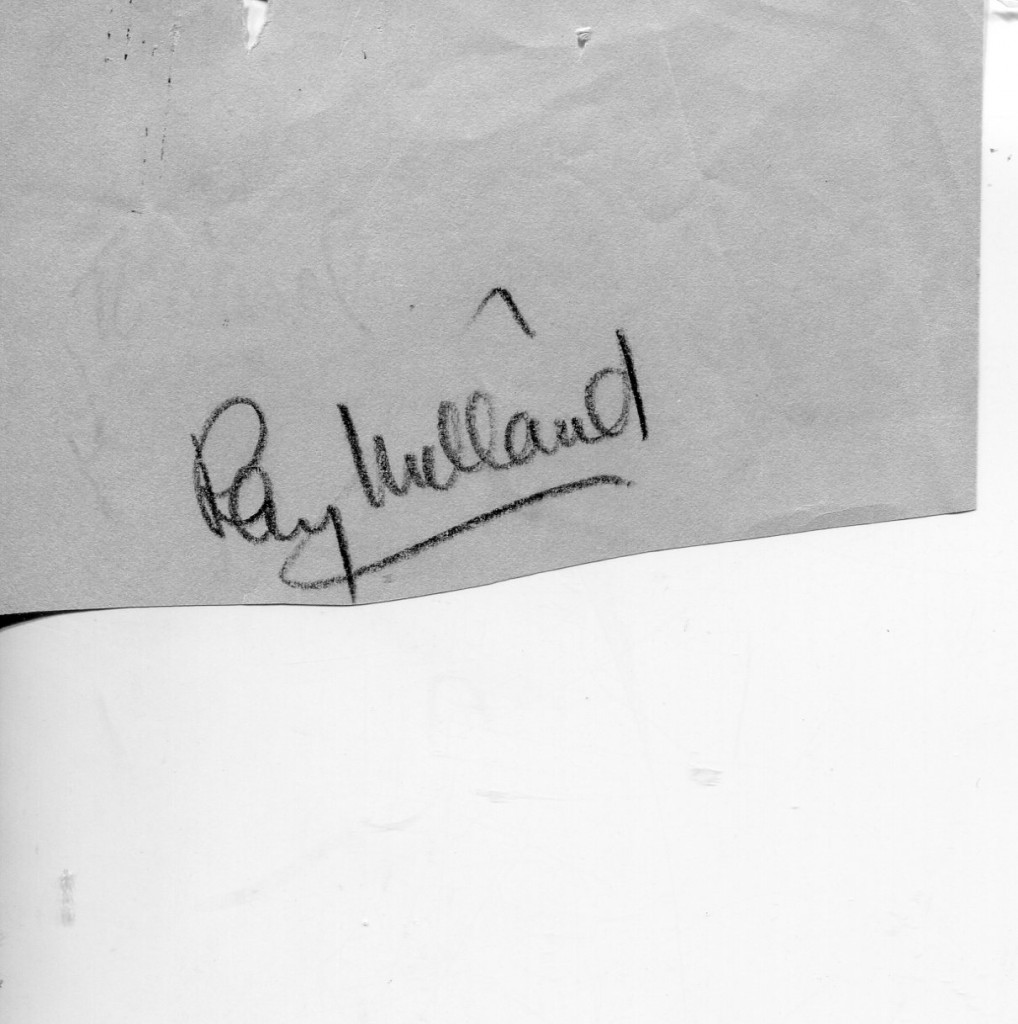

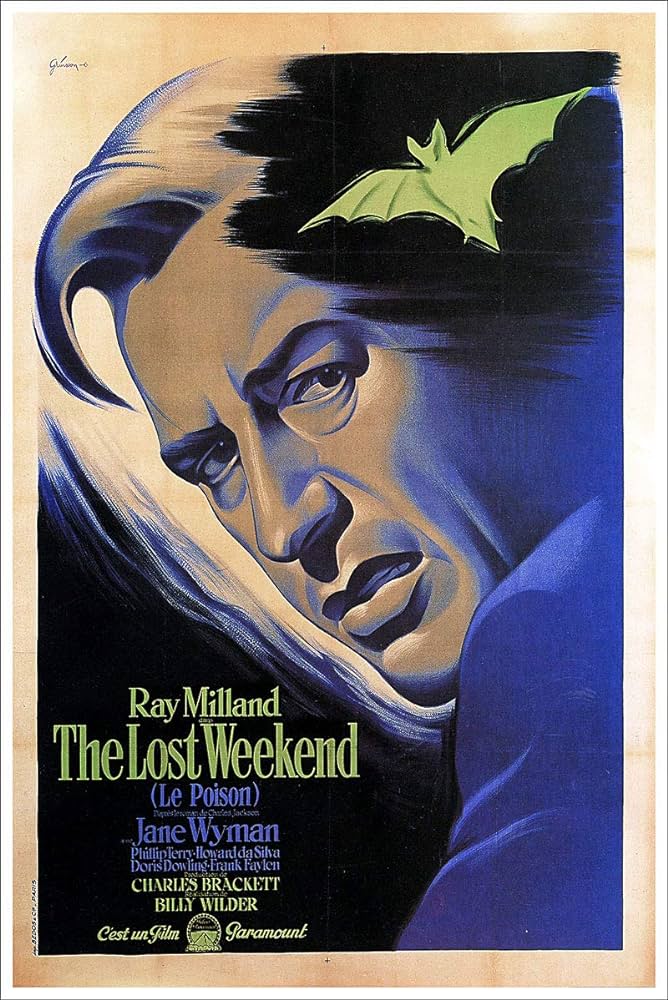

Ray Milland was named Best Actor of 1945 for his performance as an alcoholic writer in The Lost Weekend. It was a career making film — and a record making Oscar® acceptance. Milland is the only Best Actor winner to have not spoken a single word when accepting the Oscar. Instead of a speech, Milland simply bowed and made a graceful exit. In his career, like his speech, Milland’s style was often understated. He spent many years in Hollywood playing B-movie romantic leads and the buddies and rivals of the films’ male stars. The Lost Weekend should have launched Milland into stardom at long last. It proved, instead, to be the pinnacle of a 50-year career of an actor who didn’t take Hollywood fame too seriously and was willing to take on roles others might not equate with an Oscar® winner.

Milland was born Reginald Alfred John Truscott-Jones on January 3, 1905 in Wales. He made his start in British films in 1929 – his first two films were The Plaything and The Lady from the Sea (both 1929). In 1930, Milland made his way to Hollywood and took a stage name. There are several versions of how “Ray Milland” came to be. In some accounts the name was a version of his stepfather’s name Mullane. Others suggest the moniker came from the flat mill lands that surround Milland’s hometown of Neath. This second explanation mostly likely did play a part. As with most people’s life decisions, there was another influential factor – his mother. In his 1974 autobiography Wide-eyed in Babylon, Milland recalls arguing for hours with his agent over the name. Fed up, Milland claims he got up and said, “I don’t really care what you call me. I must keep the initial R because my mother had it engraved on my suitcases. Other than that, I don’t really care, but if you all don’t come up with something soon, I’m packing these suitcases and going back to the mill lands where I came from.” And so the name Ray Milland remained.

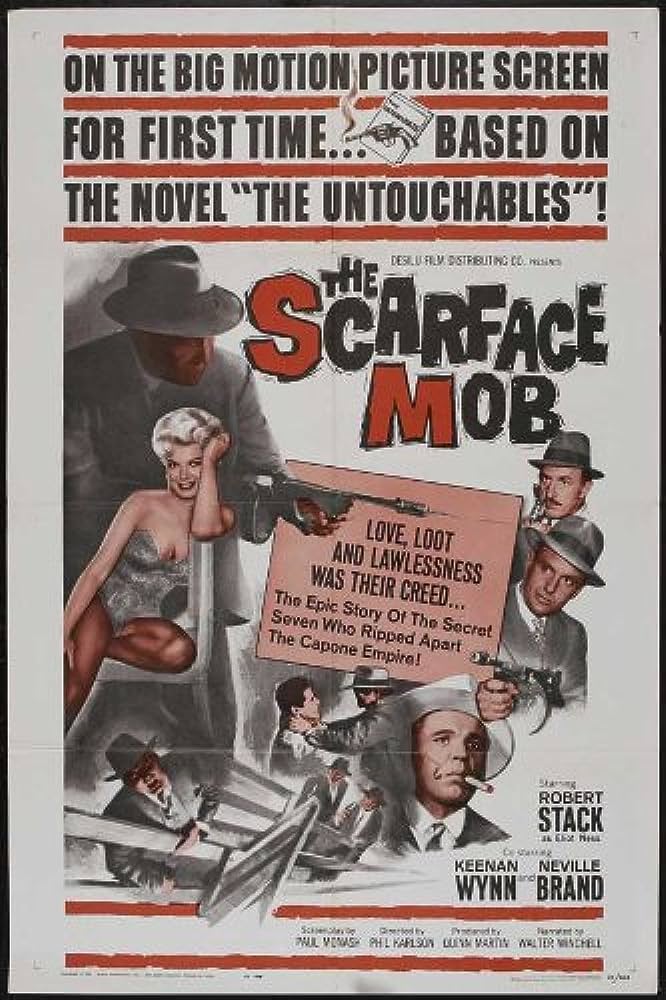

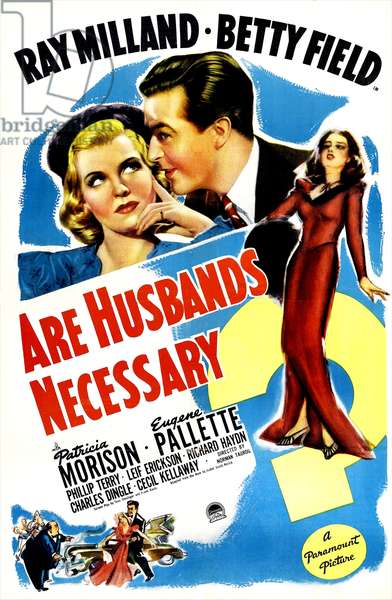

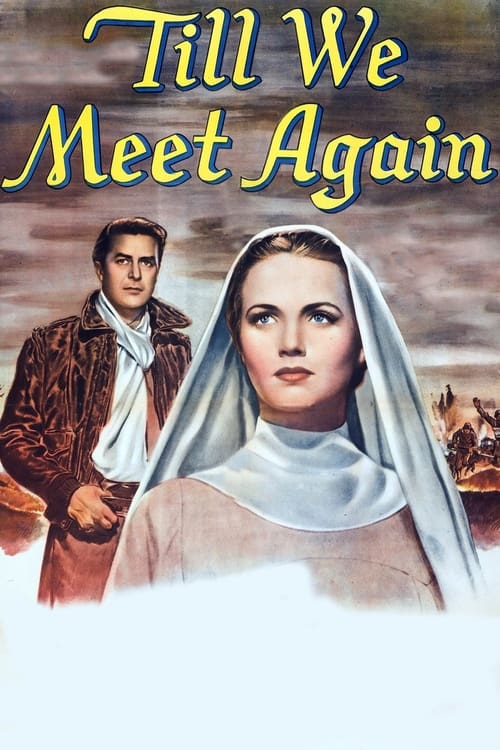

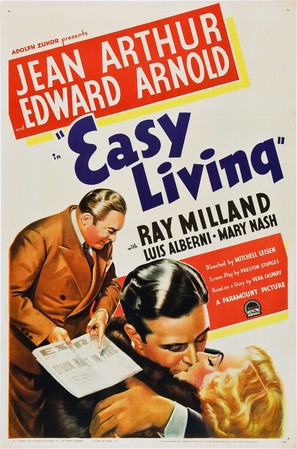

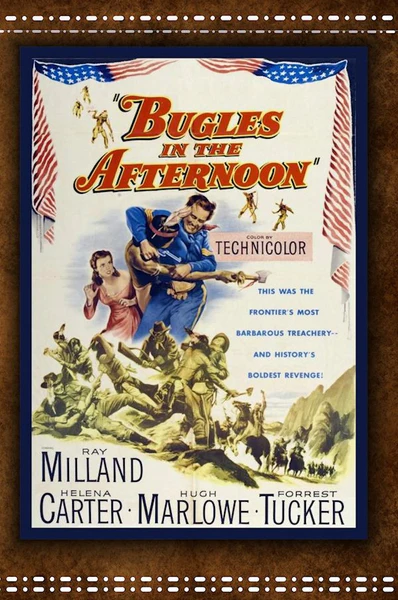

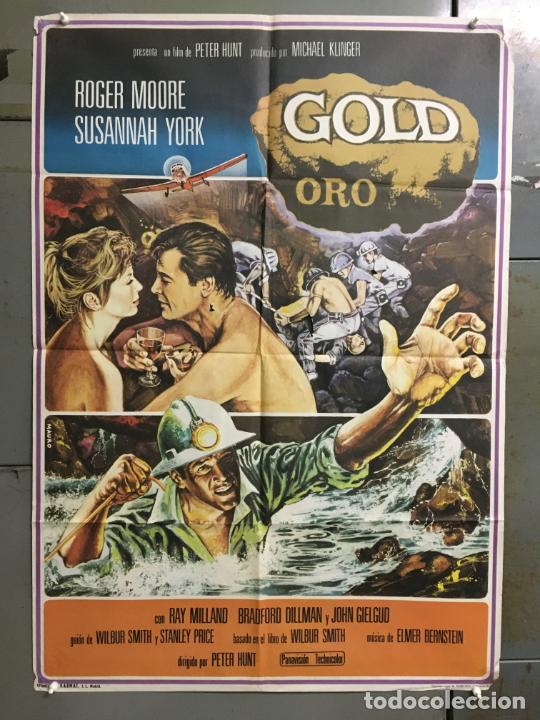

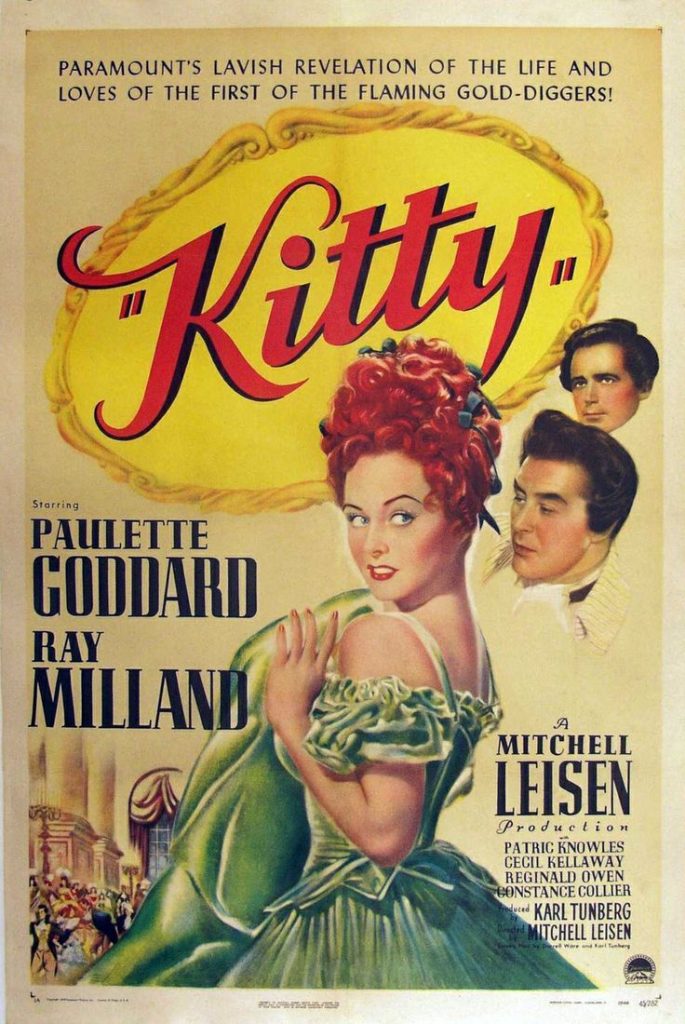

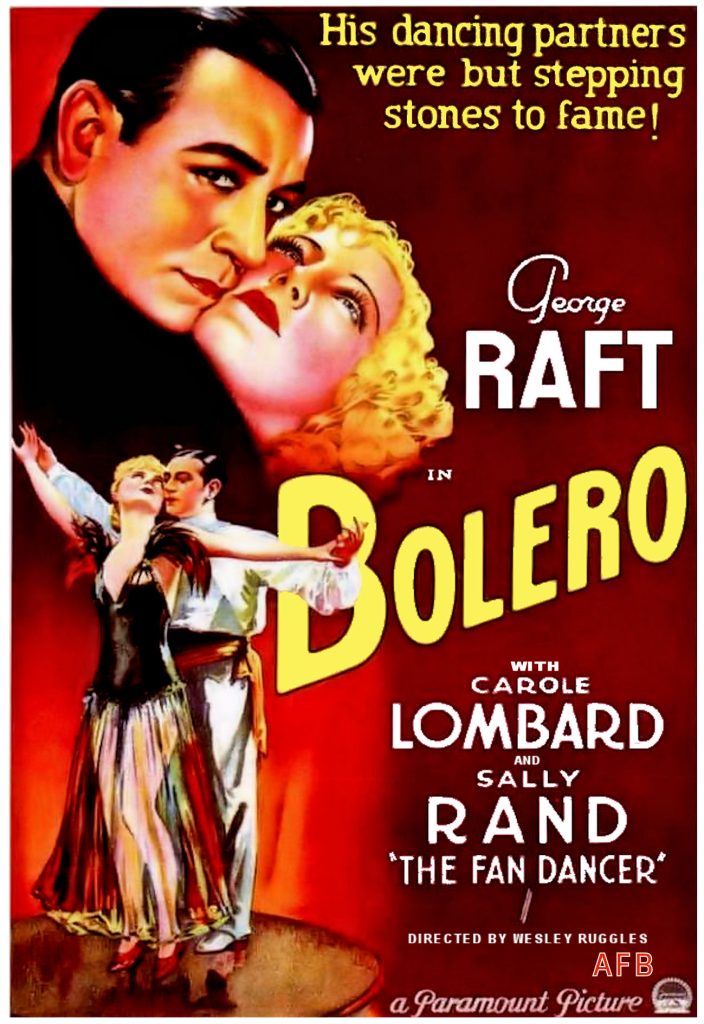

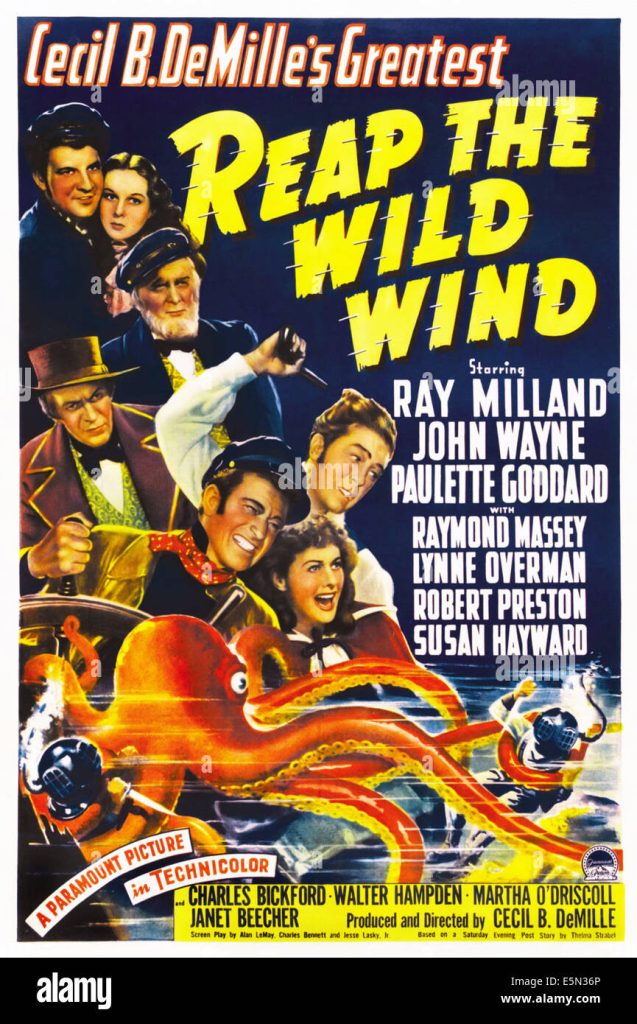

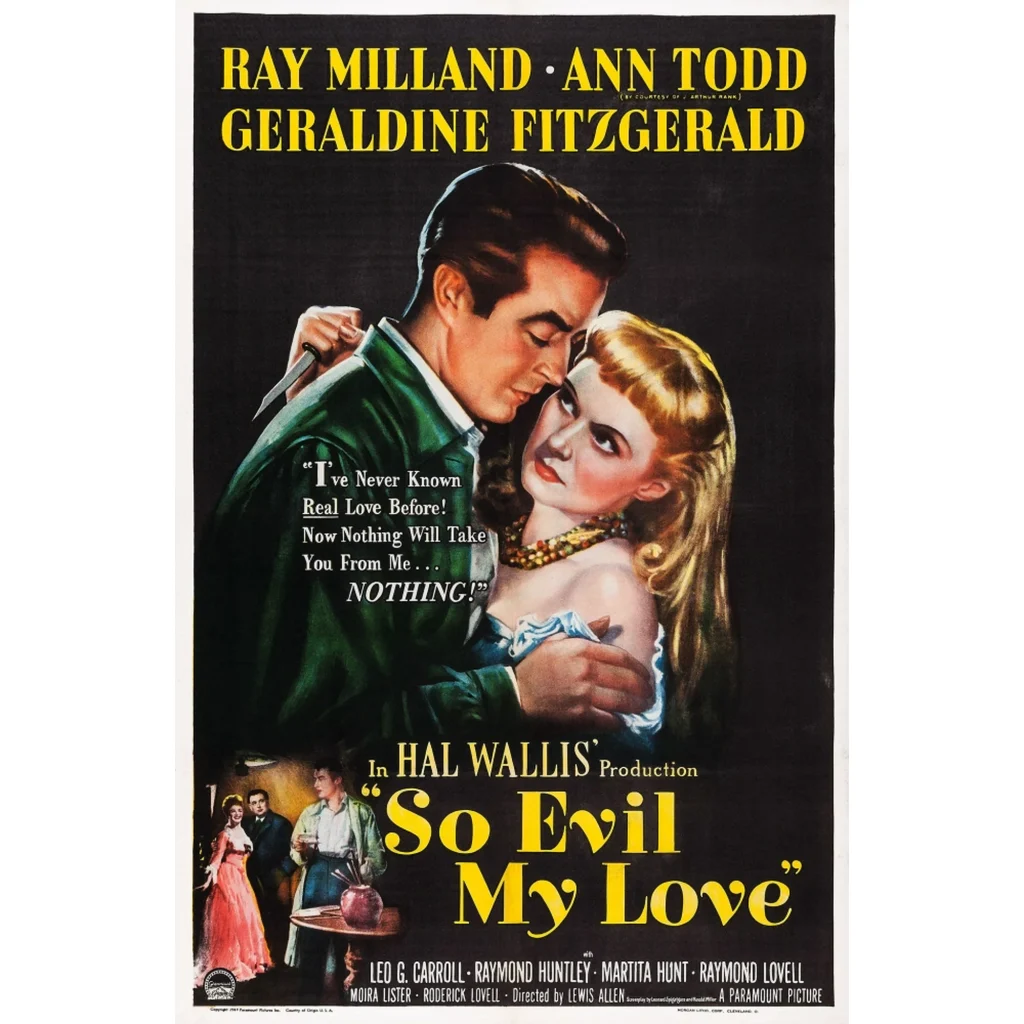

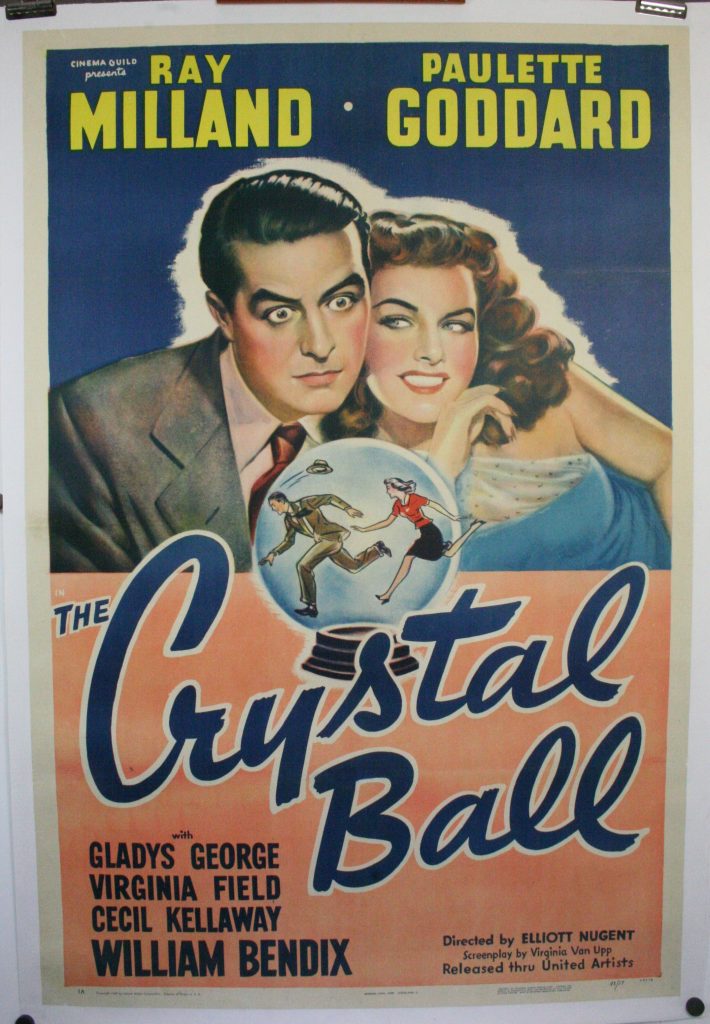

Milland’s early days in Hollywood were made up of supporting roles. One of his first films, Way for a Sailor(1930) cast him opposite John Gilbert and Wallace Beery. Other memorable films of his early career include:Strangers May Kiss (1931) with Norma Shearer and Robert Montgomery; the James Cagney-Joan Blondell crime drama Blonde Crazy (1931); the romantic comedy Just a Gigolo (1931); and Payment Deferred(1932) with Charles Laughton and Maureen O’Sullivan. By the late ’30s Milland had made the jump to more leading roles in films like Easy Living (1937) with Jean Arthur, Wise Girl (1937) opposite Miriam Hopkins, and the romantic musical-comedy Irene (1940). The 1940s brought more first rate films like the Billy Wilder comedy The Major and the Minor (1942) with Ginger Rogers, the haunted house story The Uninvited(1944) and Fritz Lang’s spy thriller Ministry of Fear (1944).

1945 would bring Milland the best role of his career with The Lost Weekend. Ironically, since this film has become so synonymous with Milland, he was not director Billy Wilder’s first choice for the part. Actors such as Cary Grant and Jose Ferrer were considered before him – and like most Hollywood stars, they wanted nothing to do with what was sure to be an unpopular film. Studio advisors also warned Milland that the film’s grim subject matter could offend viewers and hurt his career. On the other hand, Wilder, once he settled on Milland, correctly predicted that the actor would win the Oscar®. Not only was he right, but Milland also became the first actor to win both the Oscar® and the leading acting award at Cannes for the same role.

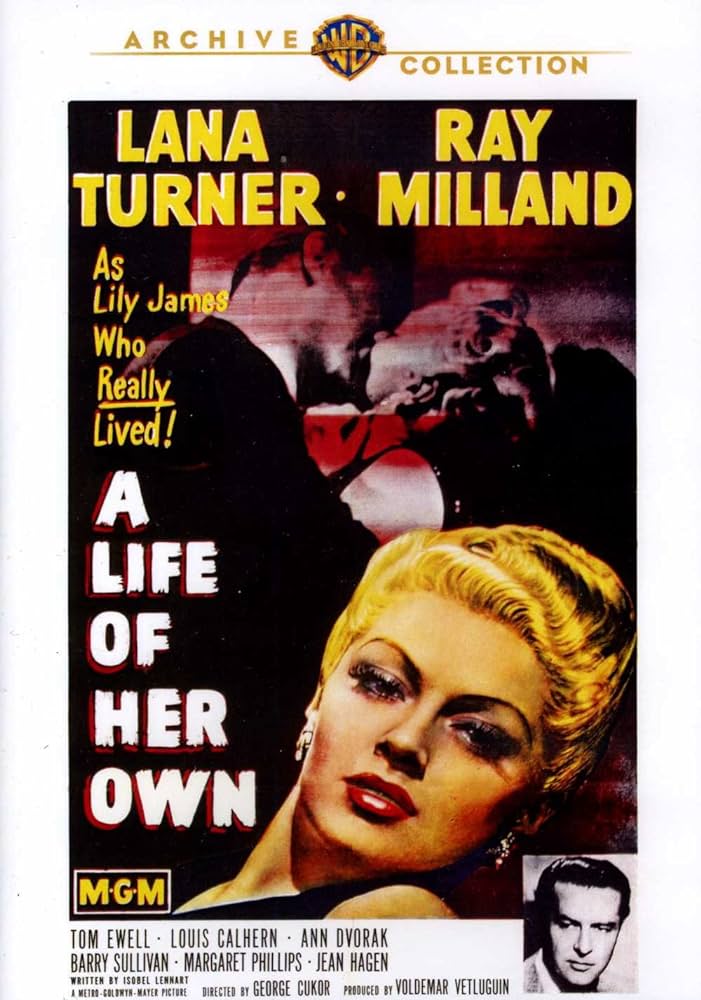

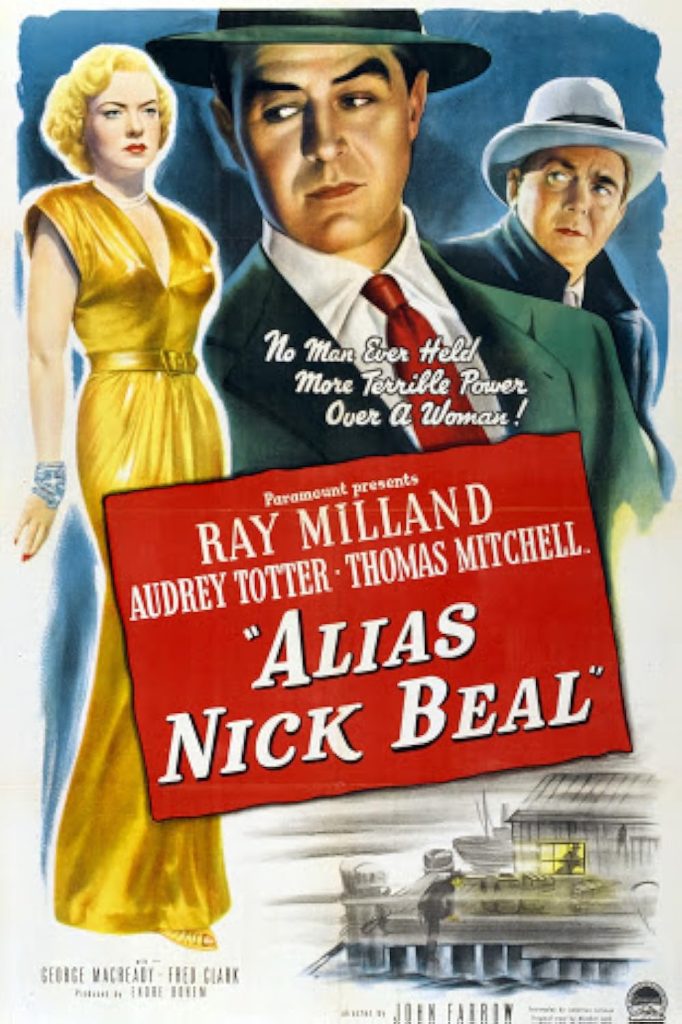

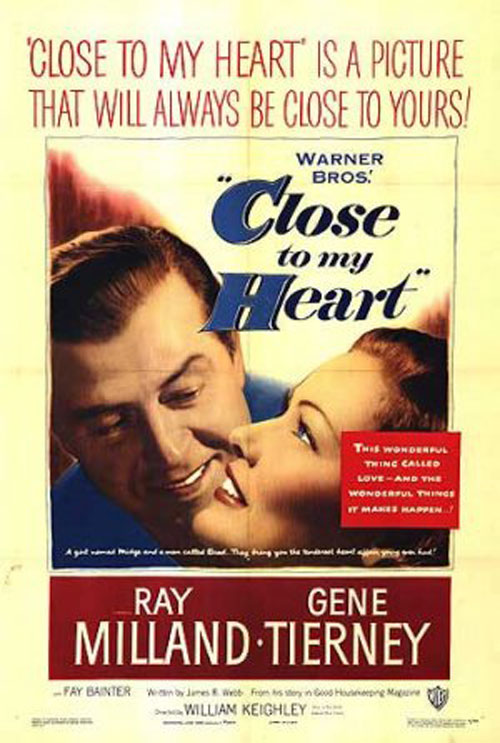

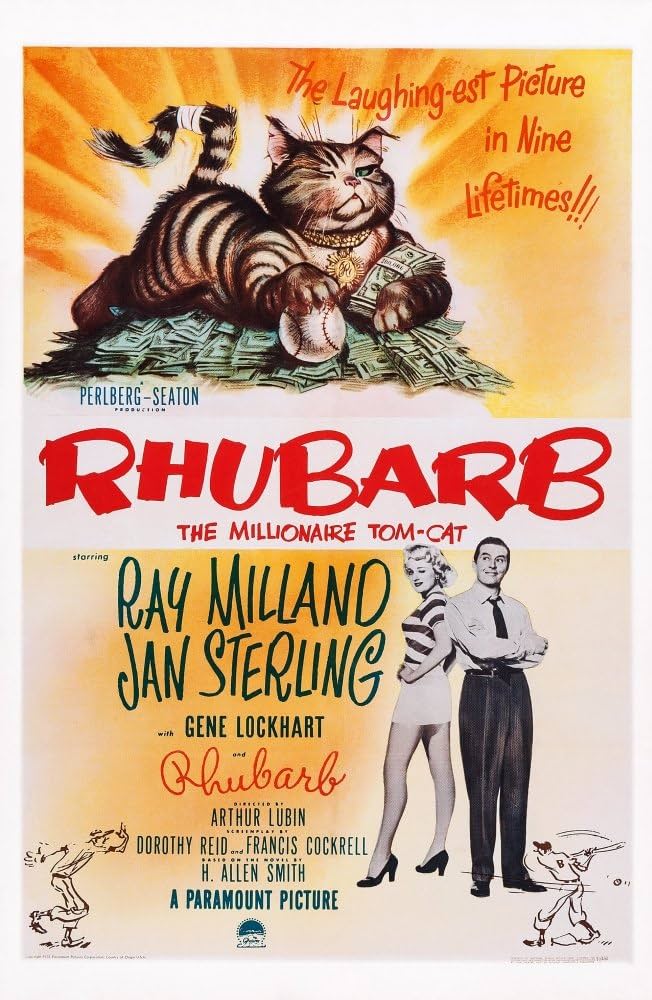

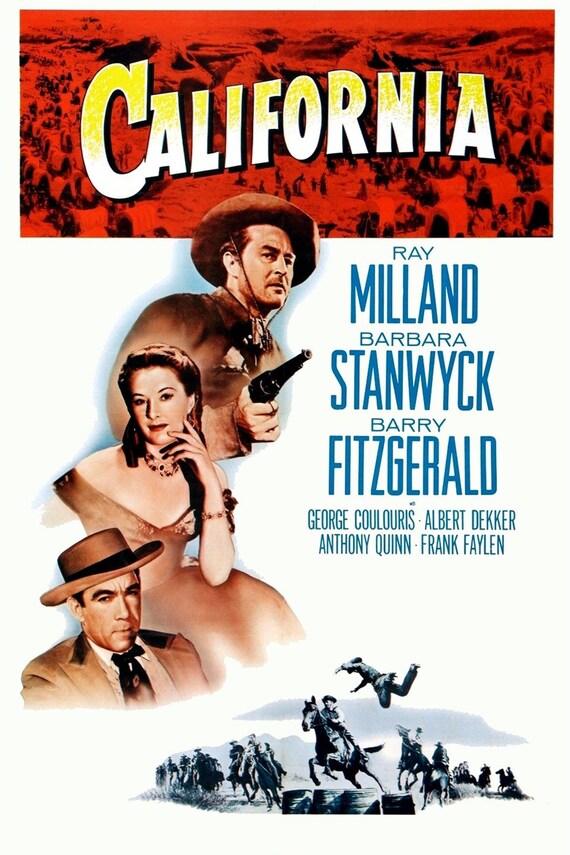

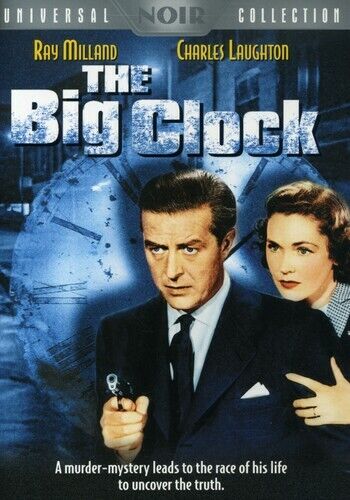

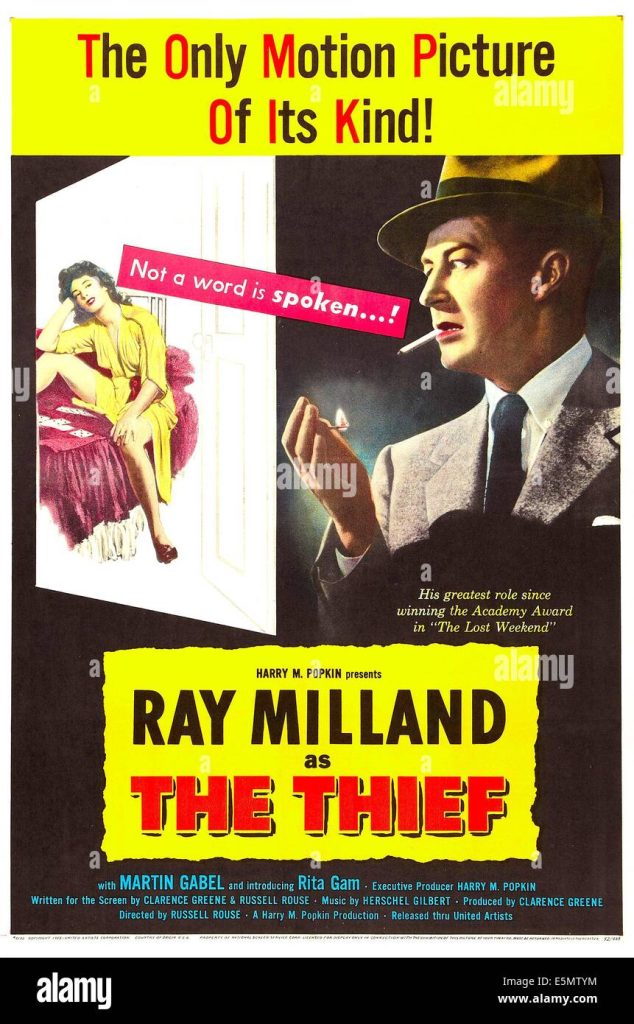

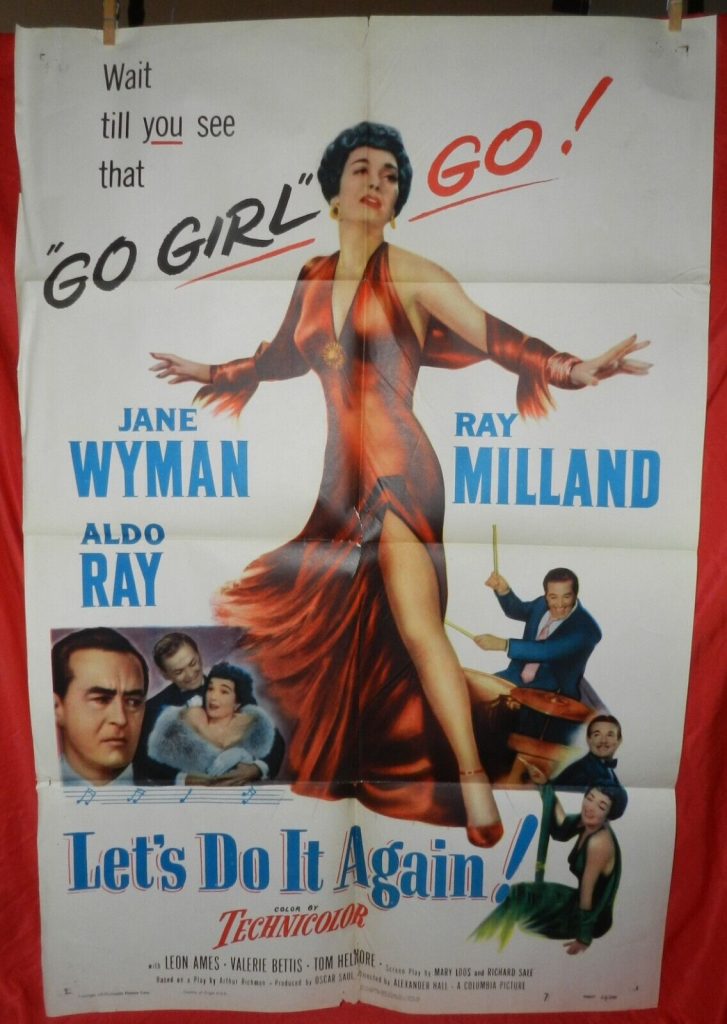

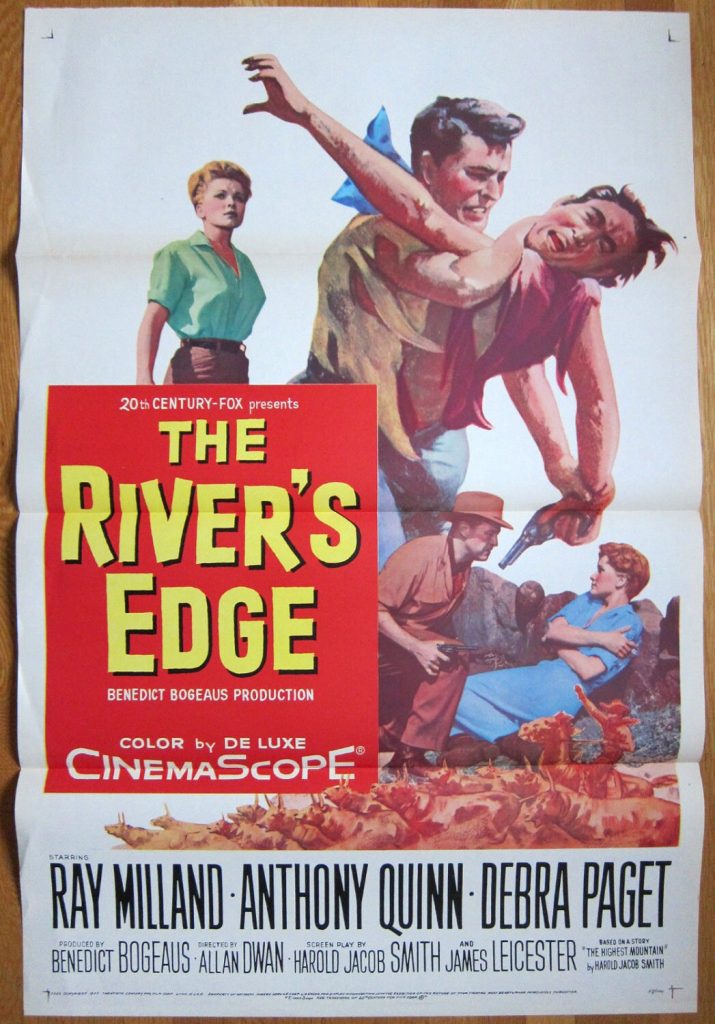

Despite his success in The Lost Weekend, Milland’s Hollywood life was largely unchanged. He followed up the film with three unremarkable pictures that might’ve been made years earlier in his career; there was the romantic comedy The Well-Groomed Bride (1946) with Olivia de Havilland, the western California (1946) with Barbara Stanwyck and the comedy The Trouble with Women (1947) opposite Teresa Wright. Two high points in those post-Lost Weekend years were the noir thriller, The Big Clock (1948), and Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder (1954) where Milland had a chance to play the villain. For the most part, however, Milland was no longer getting “A” roles.

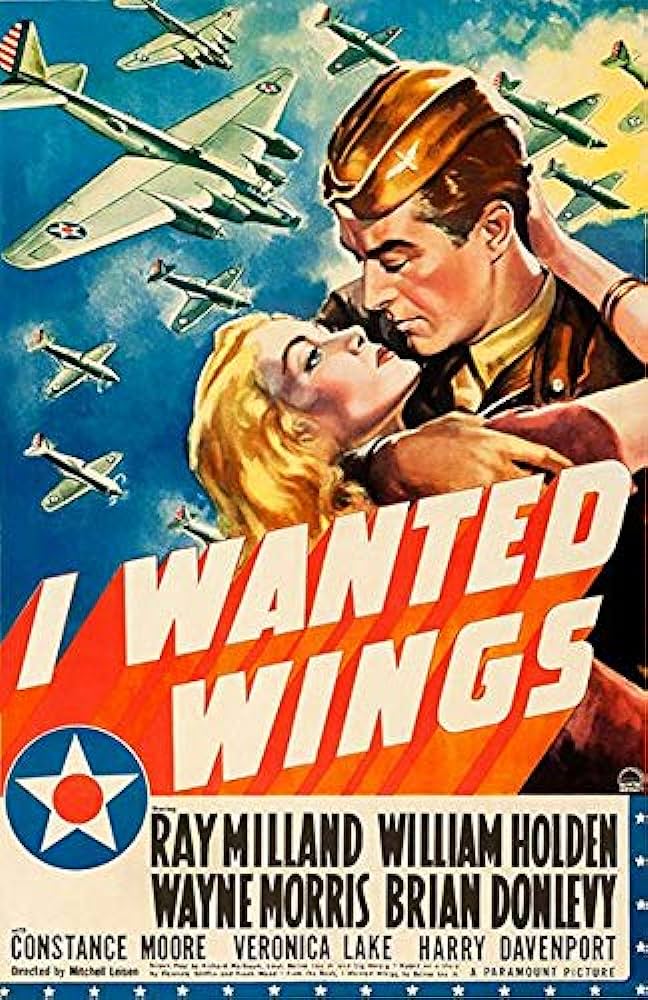

As several stories from his early career illustrate, Milland was always a risk taker. He had a near-fatal accident while filming Hotel Imperial (1939). The script called for him to jump on a horse, and being an accomplished horseman, Milland insisted on doing the stunt himself. Unfortunately when he made the jump, the saddle came loose and Milland fell into a pile of broken masonry. He was hospitalized for weeks with fractures and lacerations. Another stunt on I Wanted Wings (1941) found Milland on a test flight where he thought he’d take a jump (he was an amateur parachutist). But engine trouble forced the plane to land before he could jump. On the ground, Milland told the story to his costumer who went suddenly pale. Apparently, the parachute Milland had almost jumped with contained no parachute at all – it was just a prop. With a history of taking risks like these, it probably came as no surprise when Milland took his career in his own hands in the 1950s and began directing.

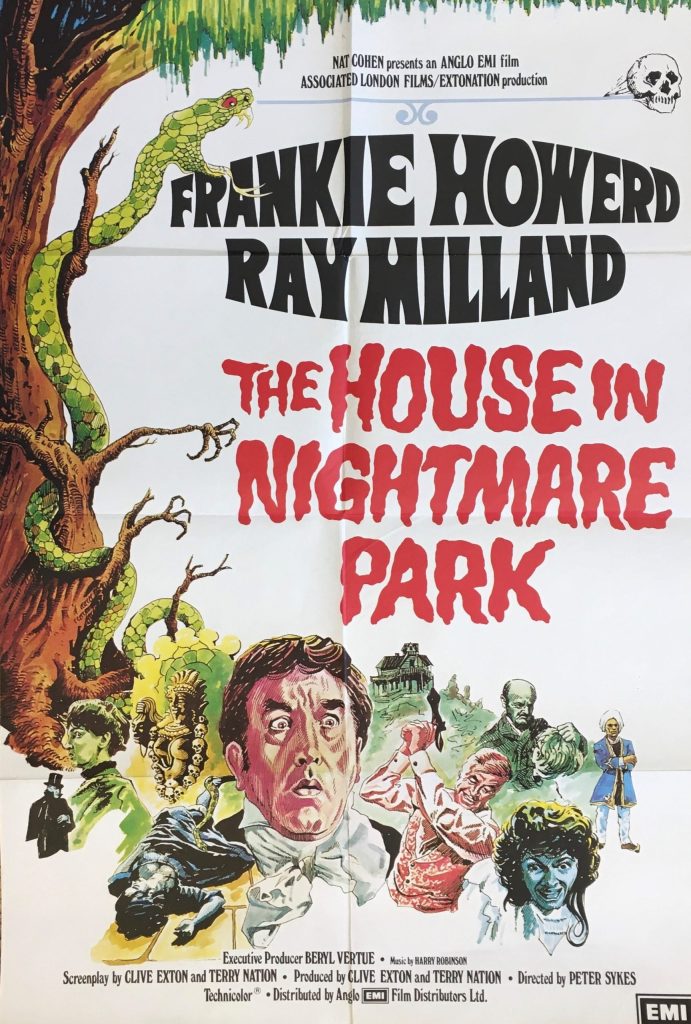

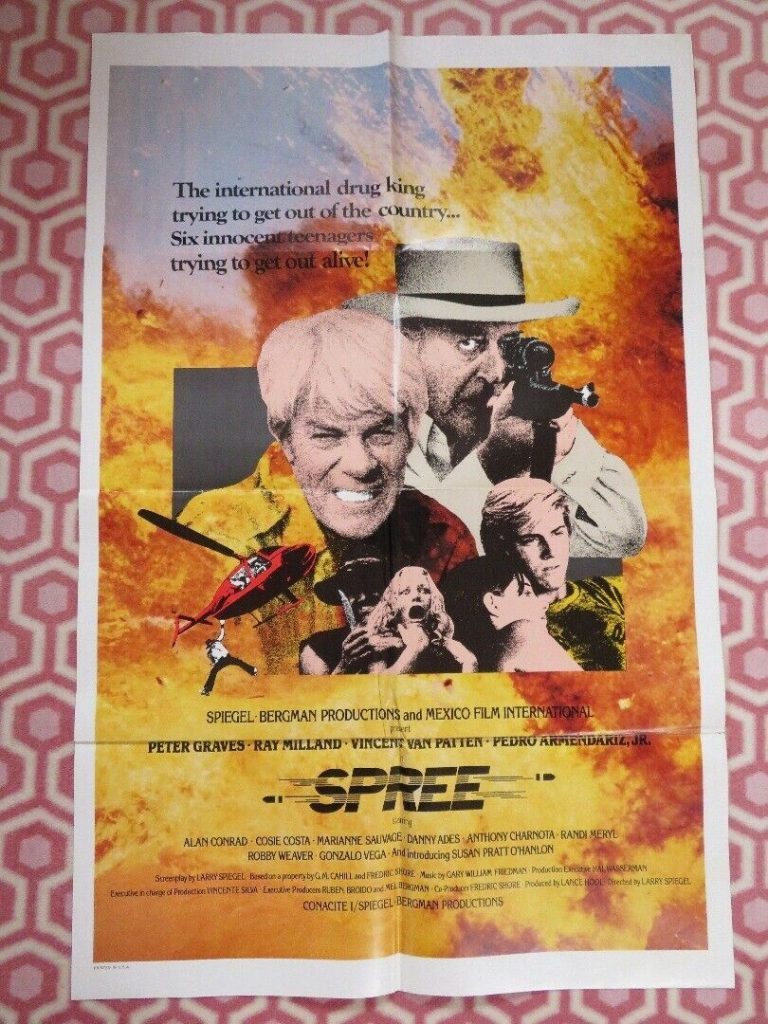

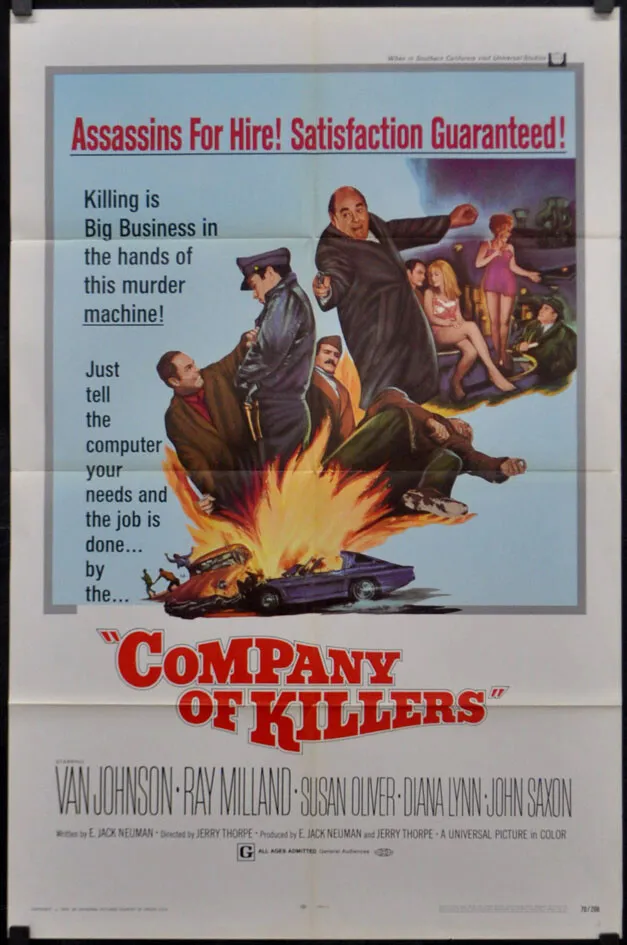

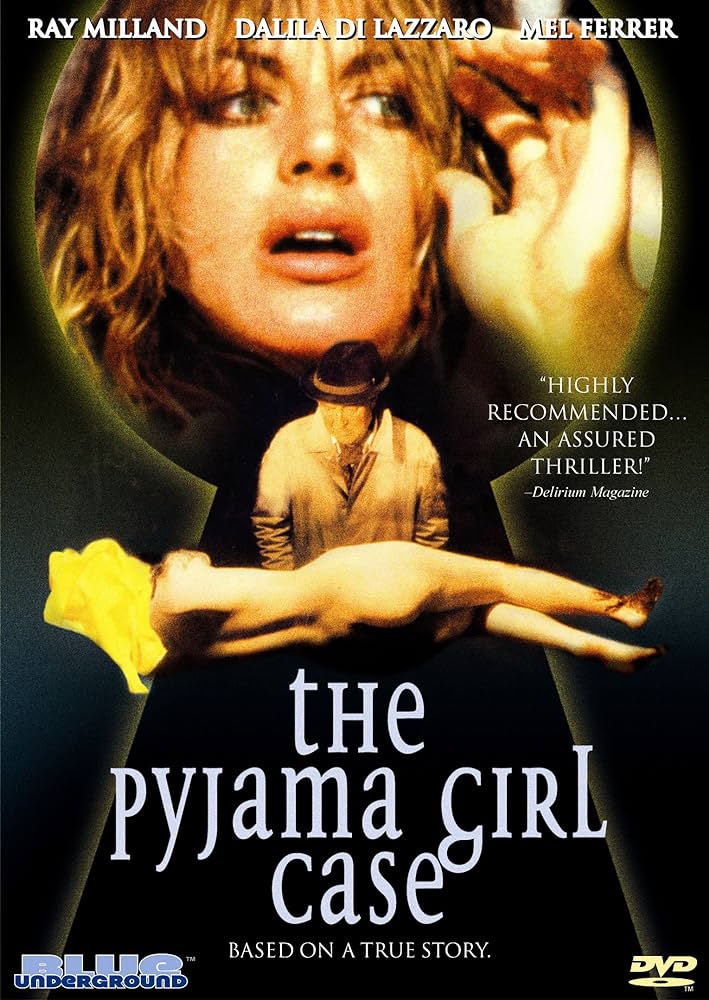

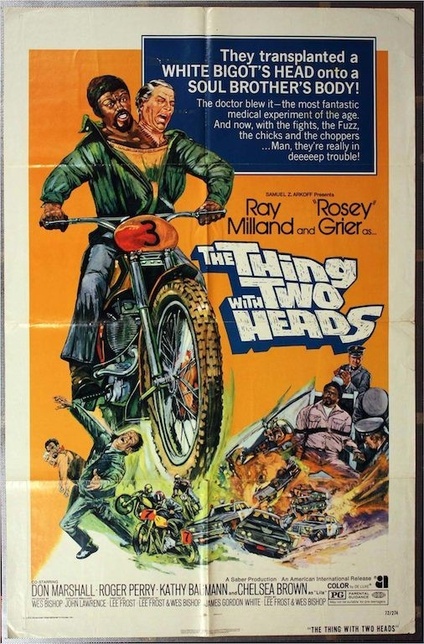

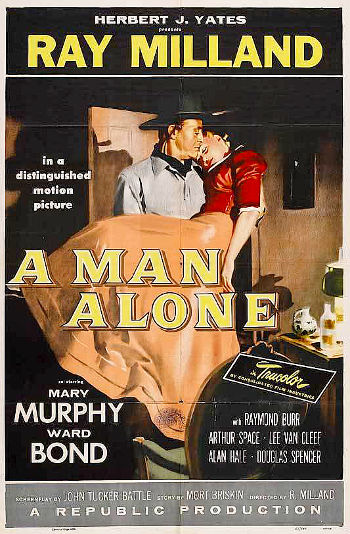

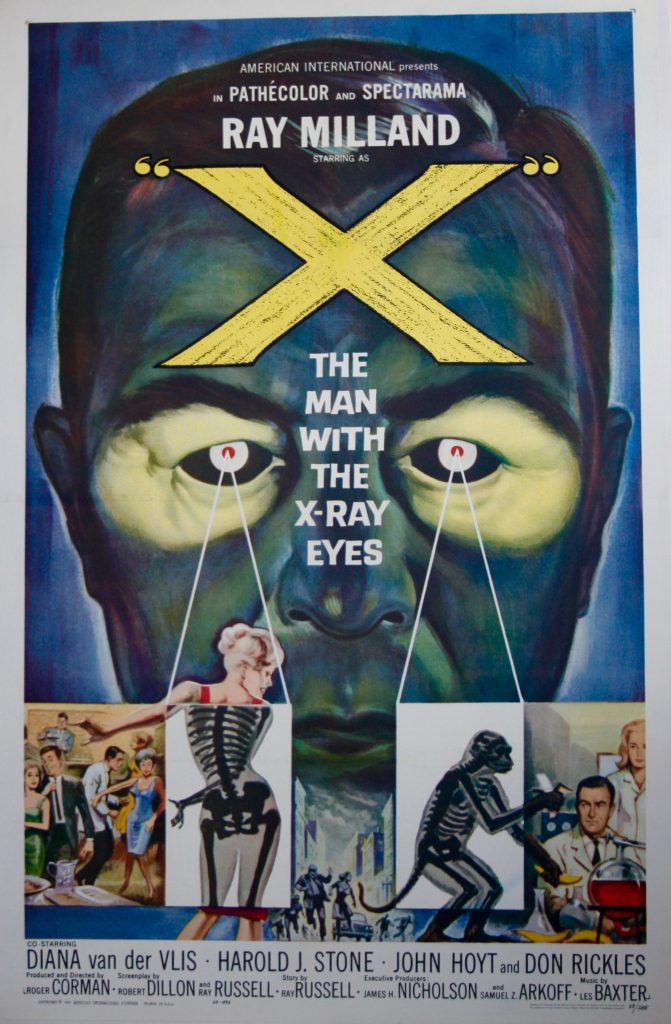

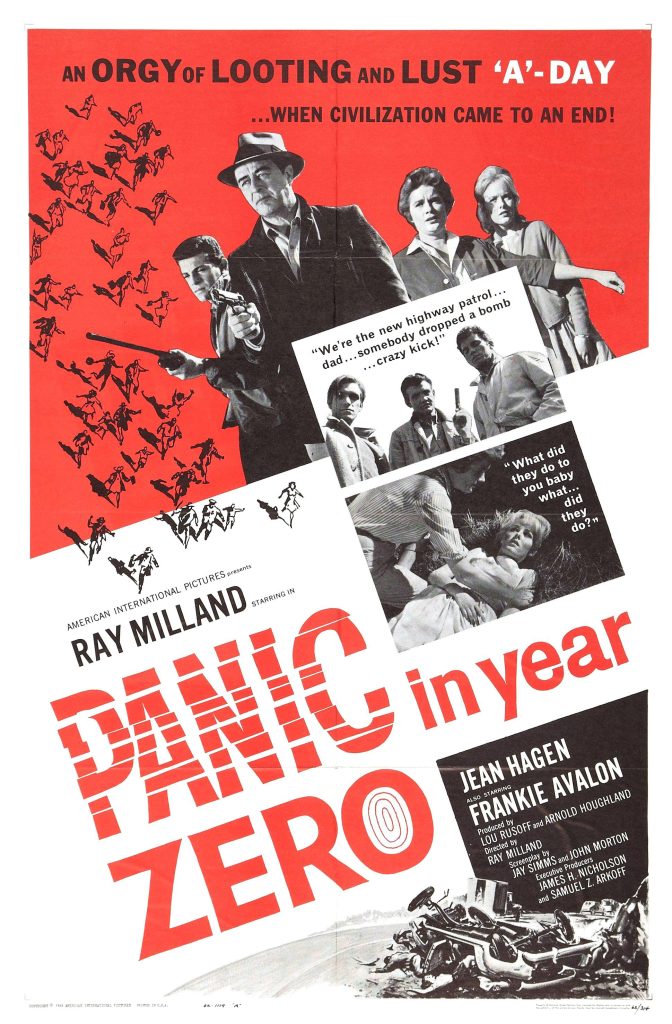

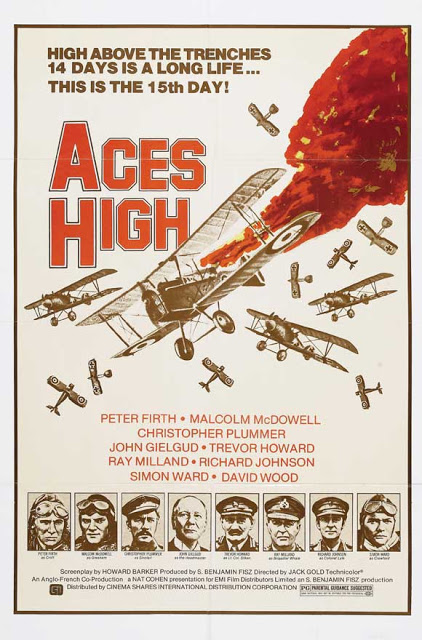

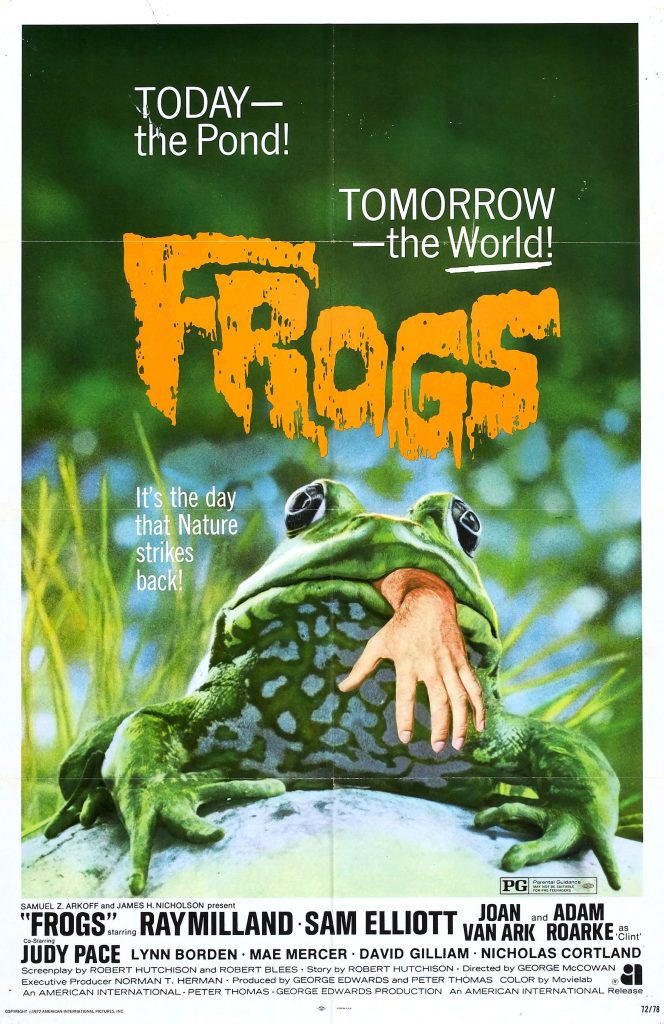

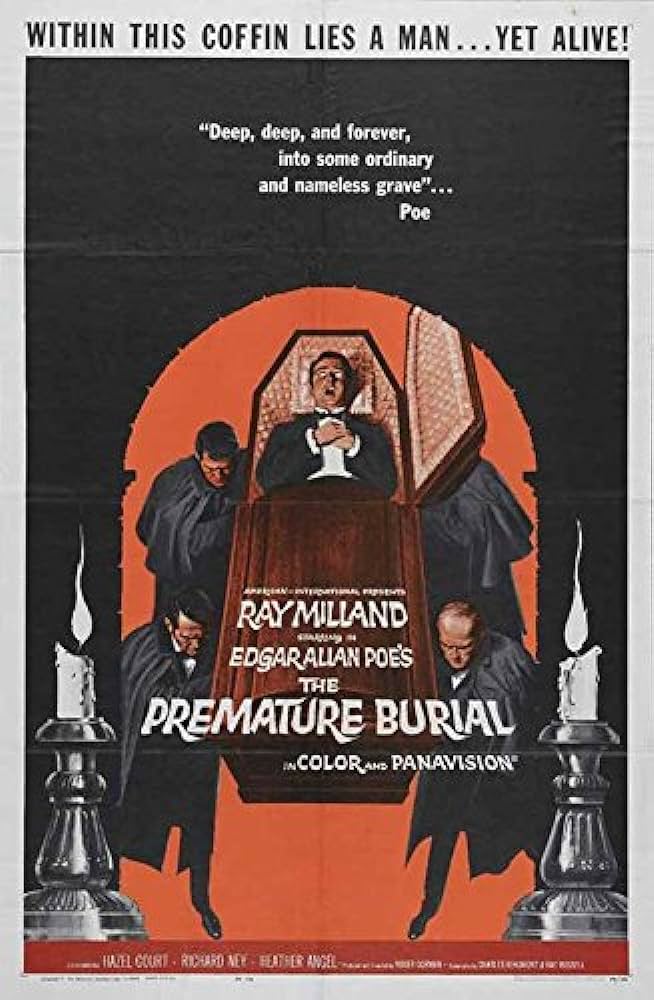

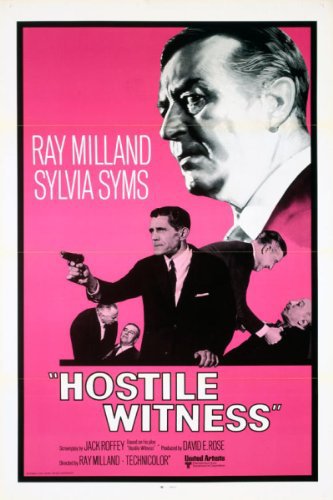

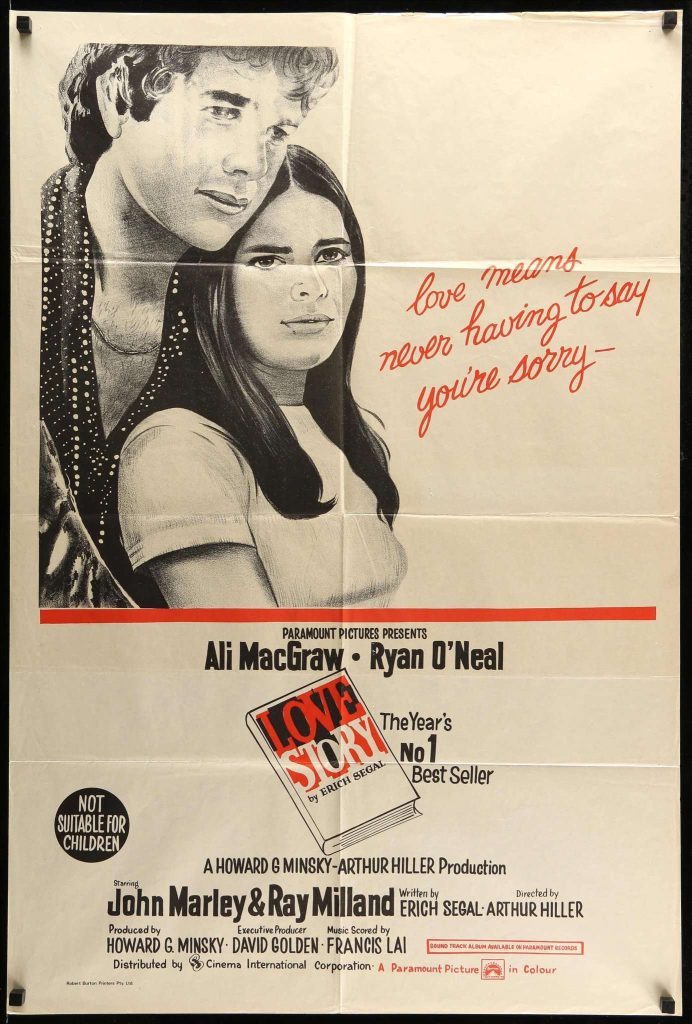

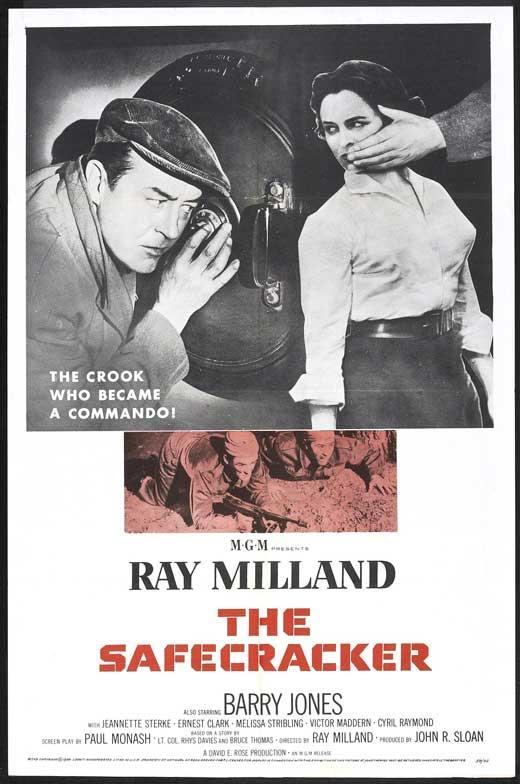

Milland made his directorial debut in 1955 on the Republic western A Man Alone. He would go on to direct several more films including The Safecracker (1958) and Panic in the Year Zero! (1962). In his later career, Milland turned his attention largely to television. He co-starred in two TV series – the comedy Meet Mr. McNuttyand the crime-drama Markham. He also appeared in a number of made-for-TV movies, including the popular mini-series Rich Man, Poor Man (1976). Milland also turned up in a number of low budget horror features such as Roger Corman’s cult sci-fi drama, X: The Man With the X-Ray Eyes (1963) and Frogs (1972). And he made something of a comeback in 1970’s Love Story, where he played Oliver Barrett III (Ryan O’Neal’s father). He also starred as an evil business mogul in Disney’s Escape to Witch Mountain (1975).

Never one to be interested in the limelight, Milland was, on a personal level, something of a book-lover and homebody. He was married to the same woman, his wife Malvina, from 1932 until his death on March 10, 1986.

by Stephanie Thames

The above TCM profile can also be accessed online here.