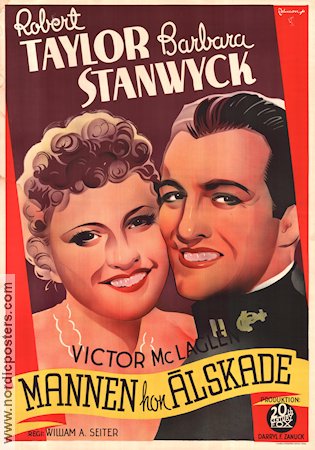

Rambunctious British leading man (contrary to popular belief, he was of Scottish ancestry, not Irish) and later character actor primarily in American films, Victor McLaglen was a vital presence in a number of great motion pictures, especially those of director John Ford. McLaglen (pronounced Muh-clog-len, not Mack-loff-len) was the son of the Right Reverend Andrew McLaglen, a Protestant clergyman who was at one time Bishop of Claremont in South Africa. The young McLaglen, eldest of eight brothers, attempted to serve in the Boer War by joining the Life Guards, though his father secured his release. The adventuresome young man traveled to Canada where he did farm labor and then directed his pugnacious nature into professional prizefighting. He toured in circuses, vaudeville shows, and Wild West shows, often as a fighter challenging all comers. His tours took him to the US, Australia (where he joined in the gold rush) and South Africa. In 1909 he was the first fighter to box newly-crowned heavyweight champion Jack Johnson, whom he fought in a six-round exhibition match in Vancouver (as an exhibition fight, it had no decision). When the First World War broke out, McLaglen joined the Irish Fusiliers and soldiered in the Middle East, eventually serving as Provost Marshal (head of Military Police) for the city of Baghdad. After the war he attempted to resume a boxing career, but was given a substantial acting role in The Call of the Road (1920) and was well received. He became a popular leading man in British silent films, and within a few years was offered the lead in an American film, The Beloved Brute (1924). He quickly became a most popular star of dramas as well as action films, playing tough or suave with equal ease. With the coming of sound, his ability to be persuasively debonair diminished by reason of his native speech patterns, but his popularity increased, particularly when cast by Ford as the tragic Gypo Nolan in The Informer (1935), for which McLaglen won the Best Actor Oscar. He continued to play heroes, villains and simple-minded thugs into the 1940s, when Ford gave his career a new impetus with a number of lovably roguish Irish parts in such films as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and The Quiet Man (1952). The latter film won McLaglen another Oscar nomination, the first time a Best Actor winner had been nominated subsequently in the Supporting category. McLaglen formed a semi-militaristic riding and polo club, the Light Horse Brigade, and a similarly arrayed precision motorcycle team, the Victor McLaglen Motorcycle Corps, both of which led to apparently erroneous conclusions that he had fascist sympathies and was forming his own private army. The facts prove otherwise, and despite rumors to the contrary, McLaglen did not espouse the far right-wing sentiments often attributed to him. He continued to act in films into his 70s and died, from heart failure, not long after appearing in a film directed by his son, Andrew V. McLaglen.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Jim Beaver <jumblejim@prodigy.net>