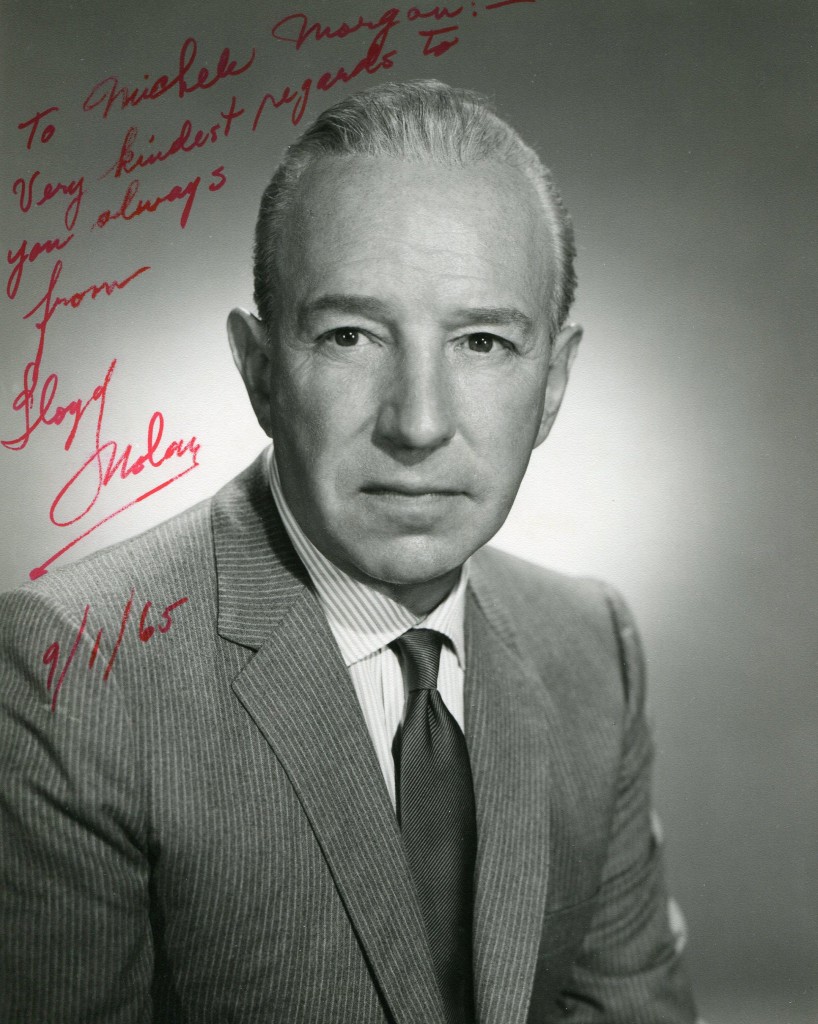

Norman Lloyd was born in 1914 in Jersey City. He was a memorable villian in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Saboteur” in 1942. He was also featured by Hitchcock in “Spellbound”. In the 1980’s he starred in the very popular medical drama “St. Elsewhere” which ran from 1983 to 1988.

TCM Overview:

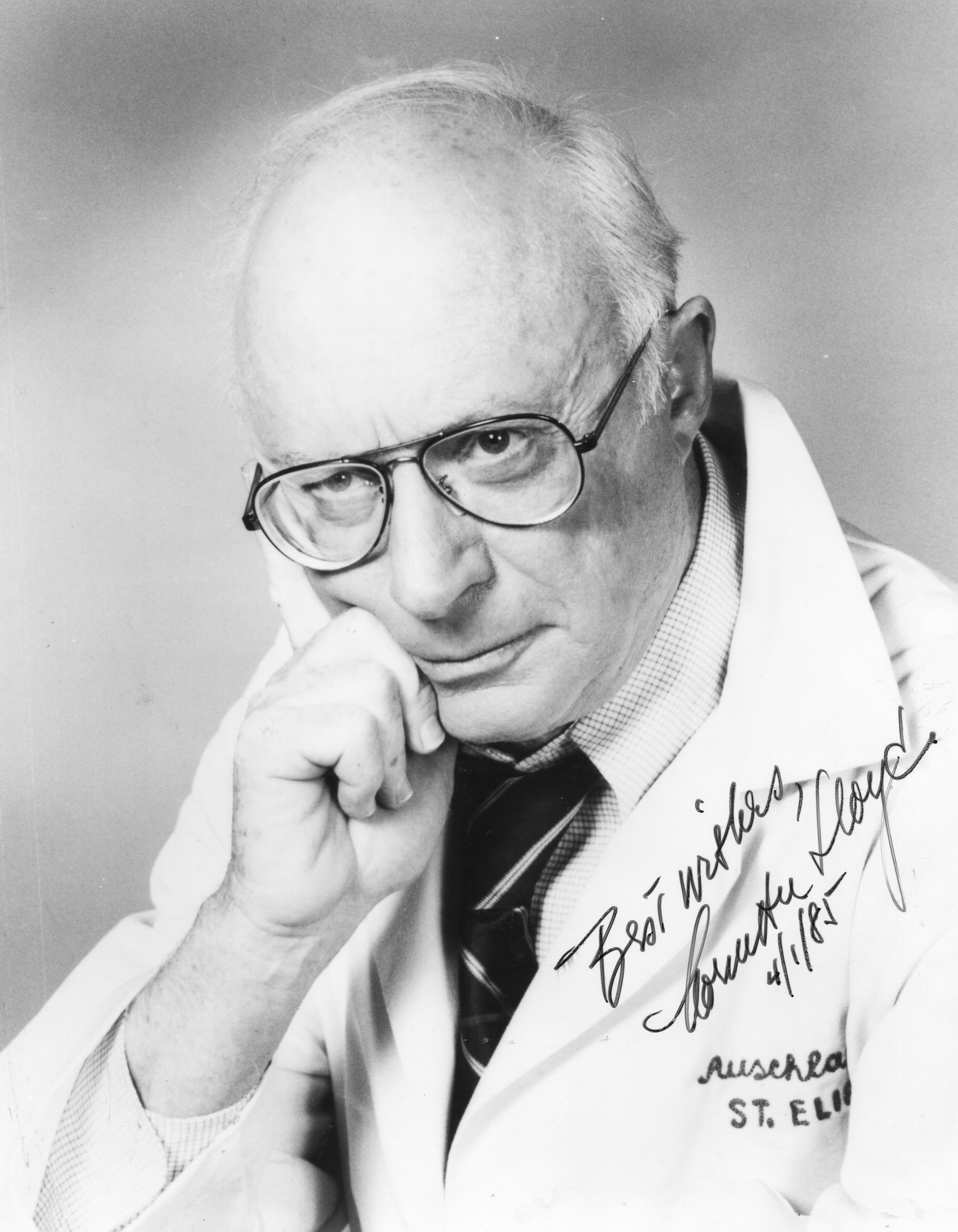

One of the most respected figures in entertainment history, actor-producer-director Norman Lloyd’s résumé read like a roll call of 20th century icons. Among his collaborative partners and directors were Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Jean Renoir, Lewis Milestone and John Houseman; each of whom employed his crisp, professional screen and stage presence in such efforts as “Saboteur” (1942), “Spellbound” (1945), “A Walk in the Sun” (1945) and “Limelight” (1952). The Communist witch hunt of the 1950s briefly hampered Lloyd’s career, but Hitchcock brought him back into the limelight as the producer of his acclaimed anthology series “Alfred Hitchcock Presents (CBS/NBC, 1955-1962). Modern audiences best knew him as the sage Dr. Auschlander on “St. Elsewhere” (NBC, 1982-88), but his career was thriving long before it, and for decades after its cancellation. A legend in the film and television field, and one of the oldest working actors in show business history, Lloyd represented the pinnacle of accomplishment and endurance for generations of fans.

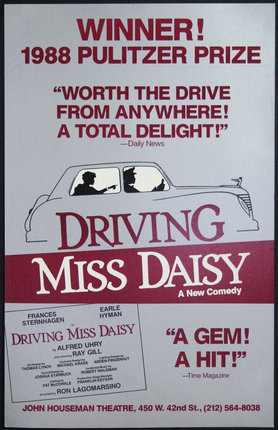

Born Nov. 8, 1914 in Jersey City, NJ, he moved with his family to Manhattan and then Brooklyn shortly after his birth. Though he showed considerable talent at tennis while a boy, his mother hoped that he would blossom into a child star, so she began enrolling him in acting classes. Several years on the amateur vaudeville circuit followed, but Lloyd did not truly embrace performing until a student in high school, where he participated in numerous plays. After graduating from college, Lloyd joined Eva Le Gallienne’s Civic Repertory Theatre in New York, which began a decade of appearances in off-Broadway and Broadway plays. In 1937, Lloyd was one of the original players in Orson Welles’ and John Houseman’s Mercury Theatre, as well as appeared as Cinna the Poet in its historic modern dress production of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar.” The following year, his performance as Johnny Appleseed in “Everywhere I Roam” drew rave reviews. Lloyd’s onscreen debut came in “The Streets of New York” (NBC, 1939), an experimental televised play directed by Anthony Mann and starring Jennifer Jones and George Colouris. In 1940, he followed Welles to Los Angeles to appear in a film version of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness.” The project never got off the ground, but it did grant Lloyd a new home base in Hollywood.

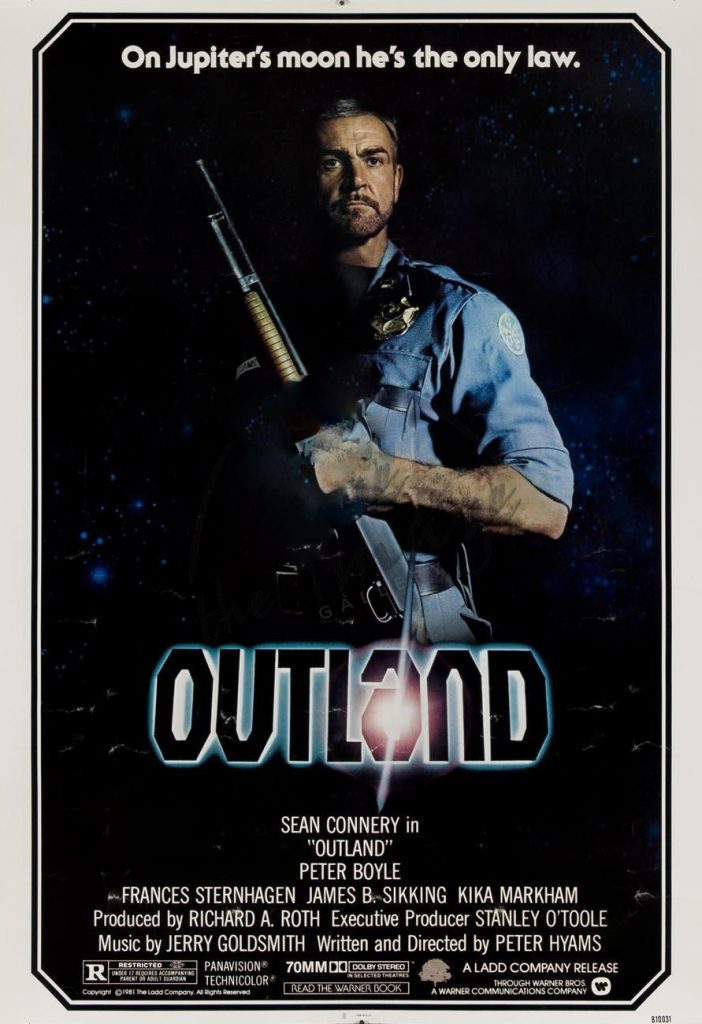

John Houseman introduced Lloyd to Alfred Hitchcock, who was looking for an unknown actor to play a dastardly Nazi spy in his thriller “Saboteur” (1942). The film’s closing sequence, which pits hero Robert Cummings against Lloyd in a fight atop the Statue of Liberty before the latter plunges to his death, was among the most iconic scenes in Hitchcock’s career. The film also served as a beginning of a three-decade partnership and friendship between Lloyd and the director, who would subsequently cast him in “Spellbound” (1945) as a patient of psychiatrist Ingrid Bergman. Lloyd worked as a character actor for some of the most significant film directors of the 1940s and 1950s. He was a churlish henchman for J. Carrol Naish’s misguided farmer in Jean Renoir’s Oscar-nominated “The Southerner” (1945), then segued to the philosophical Army scout in Lewis Milestone’s “A Walk in the Sun” (1945), largely regarded as one of the best films about World War II combat. In 1951, he played Bodalink the choreographer in Charlie Chaplin’s last great film, “Limelight.” Lloyd and Chaplin later co-owned the film rights for Horace McCoy’s novel, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? which they hoped to make into a film after “Limelight.” Sadly, Chaplin became persona non grata in the United States due to his alleged Communist sympathies, which prevented them from making the film. It was eventually purchased by ABC, which produced a version directed by Sydney Pollack in 1969.

The specter of Communism loomed largely over Lloyd’s career in the early 1950s. Many of his significant collaborators suffered mightily at the hands of the government witch hunt, including Joseph Losey, who directed him in the 1951 remake of “M,” as well as John Garfield, his co-star in the thriller “He Ran All The Way” (1951), which marked the end of the actor’s career after being blacklisted along with its director, John Berry, and writers Dalton Trumbo and Hugo Butler. Lloyd himself found himself targeted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities in the early 1950s, just as he was segueing into directing for television. A frequent stage director at the La Jolla Playhouse in San Diego, CA, Lloyd was approached by Jay Kantor at MCA about getting involved in the company’s initial launch into this new genre. He helmed episodes for several live theater productions, including the legendary “Omnibus” (ABC/CBS/NBC, 1952-1961) before reteaming with Hitchcock as his associate producer and occasional director for “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” (CBS/NBC, 1955-1962). Among his most memorable turns as director for the series were “Man from the South,” with Steve McQueen as a callous gambler who bet a depraved Peter Lorre that he could ignite his lighter 10 times in a row or lose a finger, and “The Jar,” based on a story by Ray Bradbury about a down-on-his-luck hillbilly (Pat Buttram) who bought a mysterious container that changed his life for the worse.

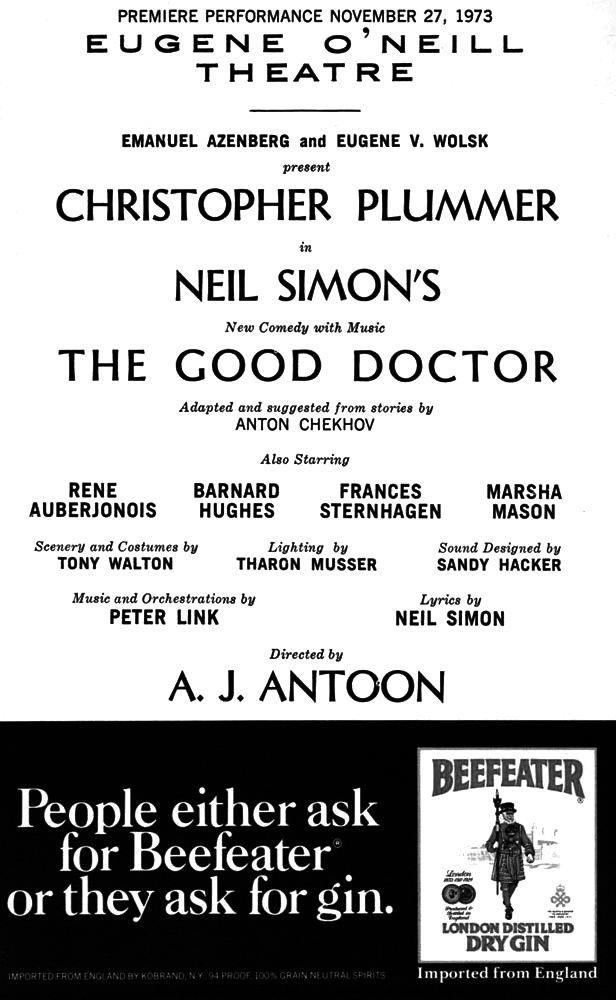

Lloyd worked primarily as a producer and director on television throughout the 1960s and 1970s, most notably on “The Name of the Game” (NBC, 1968-1971), an offbeat anthology series about the adventures of three publishing company employees, and the UK suspense anthology “Journey to the Unknown” (ITV, 1968-69) for Hammer Films. He also produced and/or directed several well-regarded television adaptations of great Broadway plays, including Lillian Hellman’s “Another Part of the Forest” (PBS, 1972) with Barry Sullivan and Andrew Prine, Clifford Odets’ “Awake and Sing!” (PBS, 1972) with Walter Matthau, and Bruce Jay Friedman’s “Steambath” (PBS, 1973) with Bill Bixby and Valerie Perrine; the latter earned Lloyd a 1974 Emmy nomination. His final efforts as producer and director came with “Tales of the Unexpected” (ITV, 1979-1983), which was largely based on the short stories of Roald Dahl.

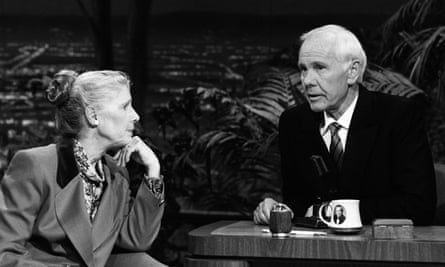

As the stigma of the blacklist began to dissipate in the 1960s and 1970s, Lloyd began to resume his acting career. Guest roles on episodic television gave way to TV and theatrical feature turns, including “Audrey Rose” (1977) as a therapist who aided a little girl plagued by the reincarnated spirit of a dead child, and as the sympathetic owner of a radio station who backed his DJs during a protest over advertising in cinematographer John Alonzo’s sole directorial effort, “FM” (1978). In 1982, he took on the role that, for many television viewers, he would remain best known: that of Dr. Daniel Auschlander on “St. Elsewhere.” A kindly mentor to its large cast of doctors and interns, Auschlander suffered from metastatic liver cancer, and was expected to pass away soon after the first few seasons. However, intensive chemotherapy put his illness in remission and he remained a vital member of the show until its final episode, when he was felled by a massive stroke. However, the finale’s legendary twist – in which the entire show was revealed as the figment of an autistic boy’s imagination – revealed him as the boy’s grandfather.

Lloyd remained active in television and the occasional feature in the years after “St. Elsewhere.” He was the authoritarian head of the boys’ school who butted heads with freethinking teacher Robin Williams in “Dead Poets Society” (1989), and the senior partner at Daniel Day-Lewis’ law firm in Martin Scorsese’s “The Age of Innocence” (1993). He reunited with his “St. Elsewhere” producers for the short-lived series “Home Fires” (NBC, 1992), and he played Dr. Isaac Mentnor, a scientist who created a time travel device using the alien spacecraft that landed in Roswell, New Mexico, in “Seven Days” (UPN, 1998-2001). Notable guest turns included a recurring role on “The Practice” (ABC, 1997-2004) as Asher Silverman, a district attorney and practicing rabbi who challenged Dylan McDermott’s Bobby Donnelly on ethical issues. In 2000, he co-starred as the Secretary of Defense in a live TV remake of “Fail Safe” (CBS) that starred George Clooney, and in 2005 – well into his ninth decade – he received rave reviews as a former English professor, now a resident at a retirement home, who bonds with Cameron Diaz’s fading wild child over poetry in Curtis Hansen’s comedy-drama, “In Her Shoes.” In 2007, Lloyd’s storied career was the subject of a documentary, “Who Is Norman Lloyd,” a gentle valentine to the actor’s life and accomplishments, as well as his lengthy marriage to actress Peggy Lloyd, whom he wed in 1936. As he approached his 100th birthday, he was still performing, most notably in a 2010 episode of “Modern Family” (ABC, 2009- ).