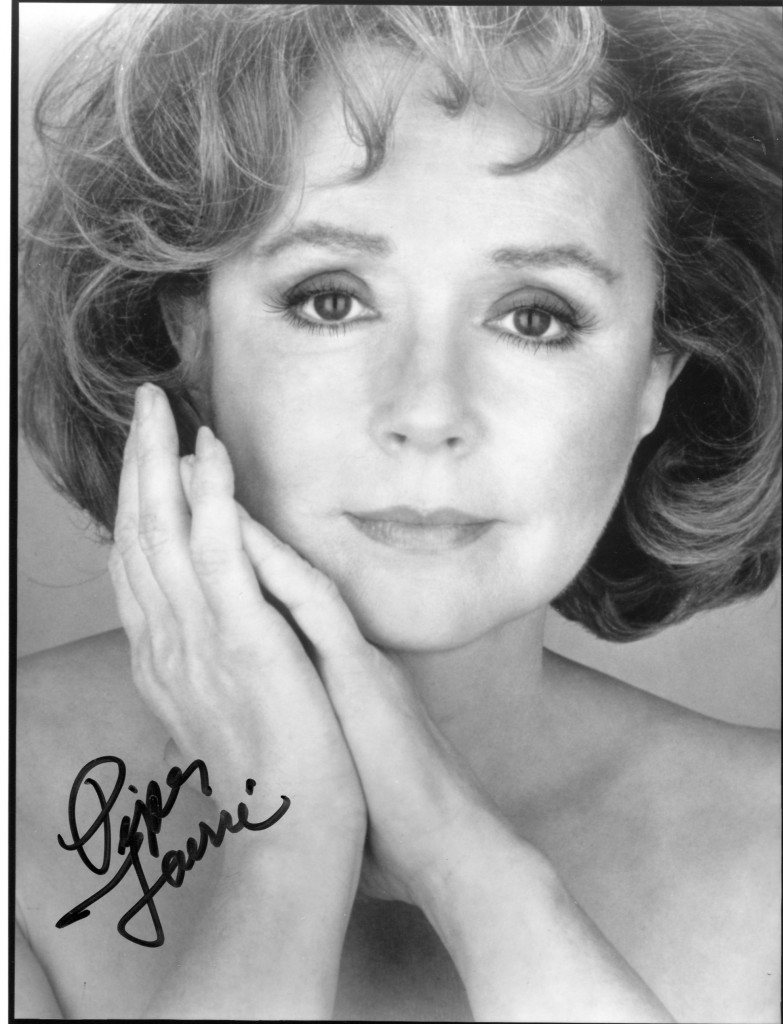

Piper Laurie was born in 1932 in Michigan. She won a contract to Universal Studios in the early 1950’s and made such films as “The Prince Who Was A Thief” with Tony Curtis, “Son if Ali Baba” also with Curtis in 1952. She gave a wonderfully realised performance opposite Paul Newman in “The Hustler”. She retired for a number of years to raise her daughter and came back in force as a character actress to be reckoned with in the 1970’s. She played Sissy Spacek’s mother in “Carrie”.

IMDB entry:

Piper Laurie was born Rosetta Jacobs in Detroit, Michigan, on January 22, 1932, to Charlotte Sadie (Alperin) and Alfred Jacobs, a furniture dealer. Her father was a Polish Jewish immigrant and her mother was of Russian Jewish descent. Her father moved the family to Los Angeles, California, when she was 6-years-old. Rosetta was a pretty red-haired little girl, but very shy, so her parents sent her to weekly elocution lessons. In addition to her lessons in Hebrew school, she studied acting at a local acting school, and this eventually led to work at Universal Studios.

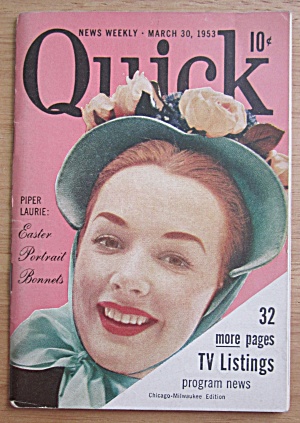

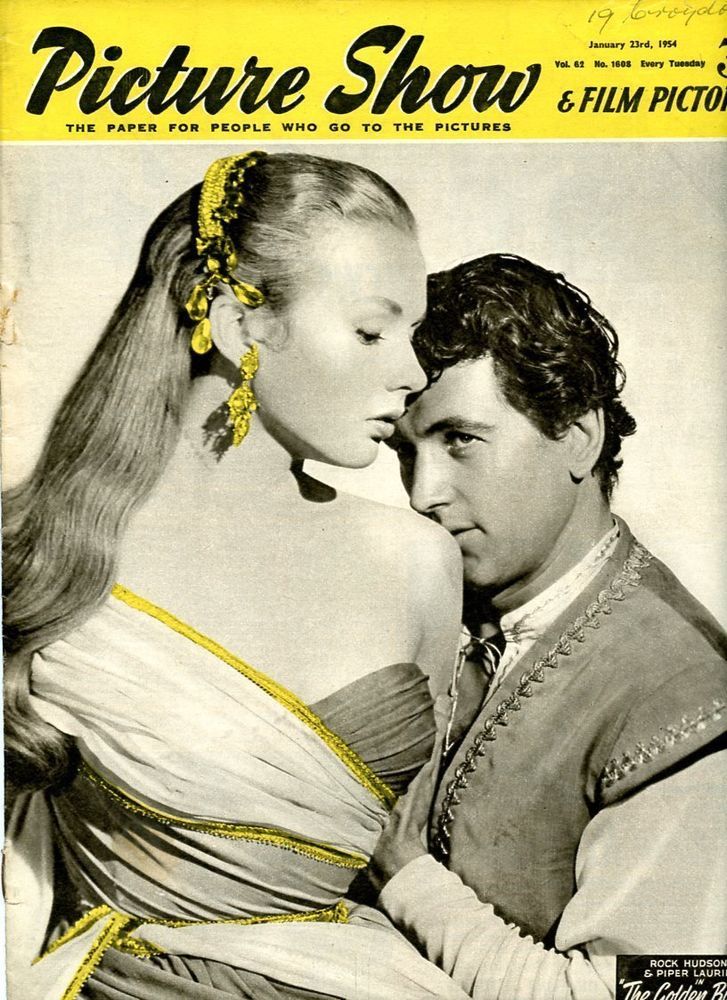

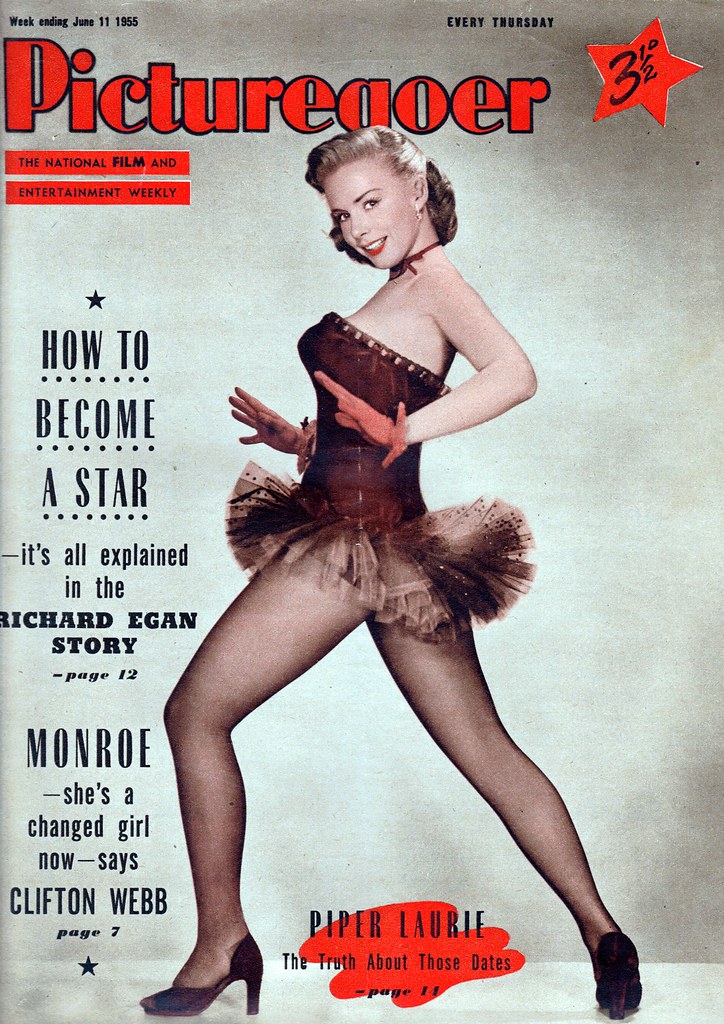

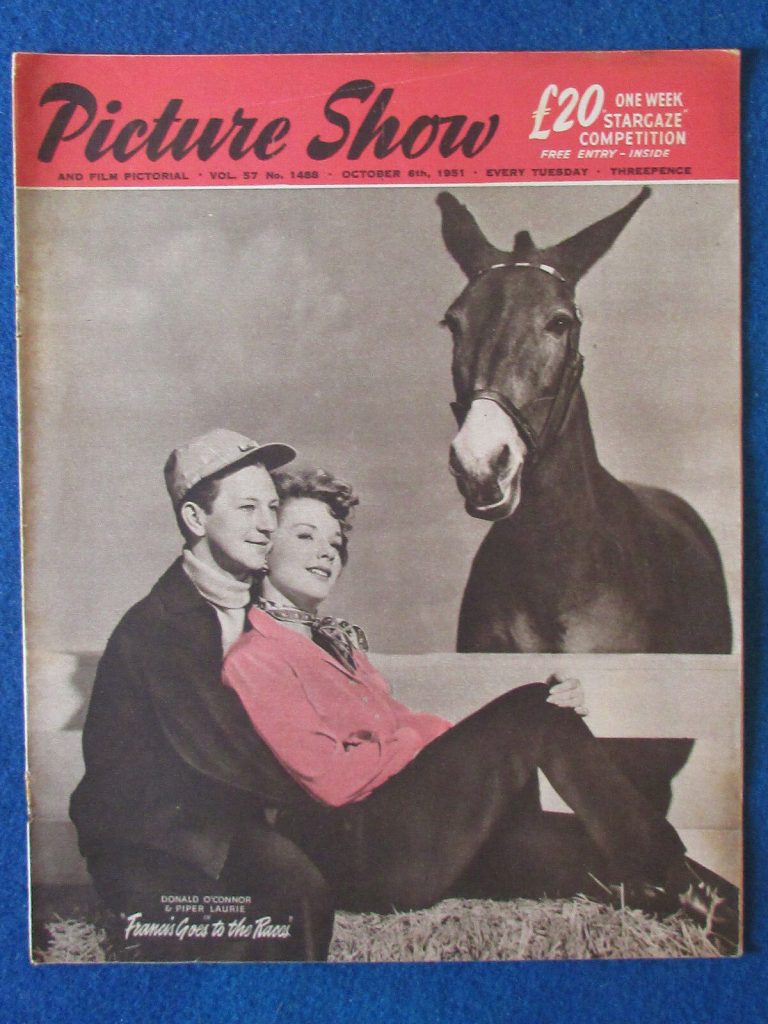

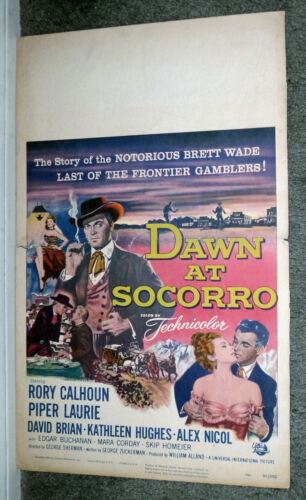

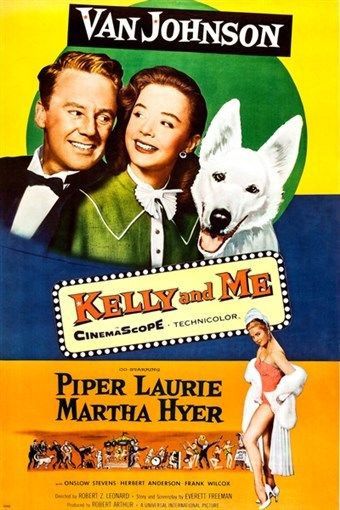

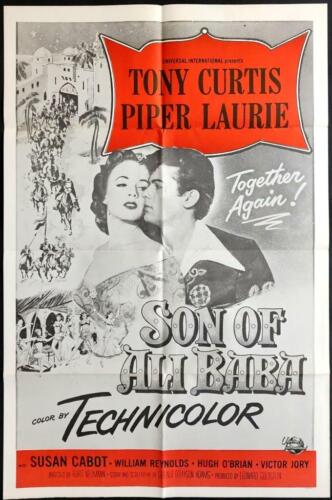

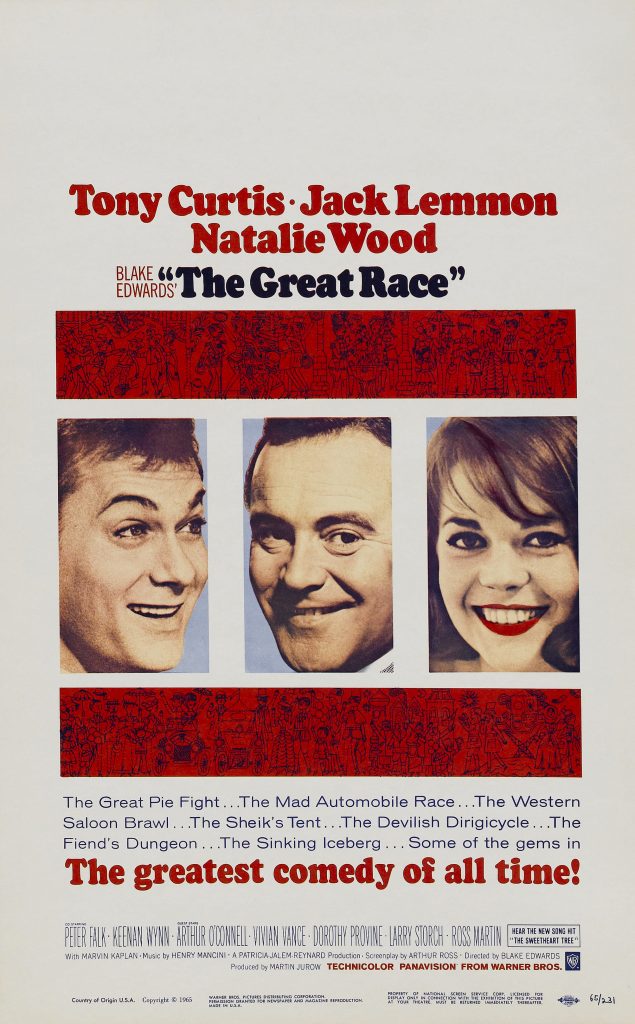

Universal had signed her as a contract player when she was only 17-years-old, and changed her screen name to Piper Laurie. She was cast in the movie, Louisa (1950), and became very close friends with her costar, Ronald Reagan. She was then cast in Francis Goes to the Races (1951) with Donald O’Connor, Son of Ali Baba (1952) with Tony Curtis, and Ain’t Misbehavin’ (1955) with Rory Calhoun. The studio tried to enhance her image as an ingénue with press releases stating that she took milk baths and ate gardenia petals for lunch. Although she was making $2,000 per week, her lack of any substantial roles discouraged her so much that by 1955 when she received another script for a Western and “another silly part in a silly movie”, she dropped the script in the fireplace, called her agent and told him she didn’t care if they fired her, jailed her or sued her.

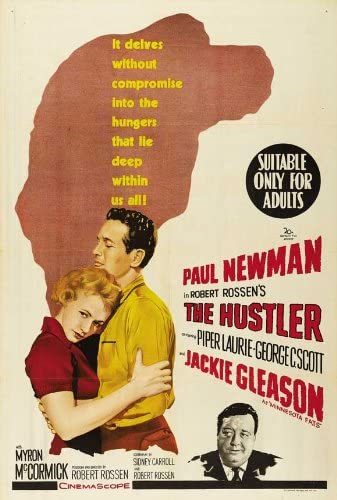

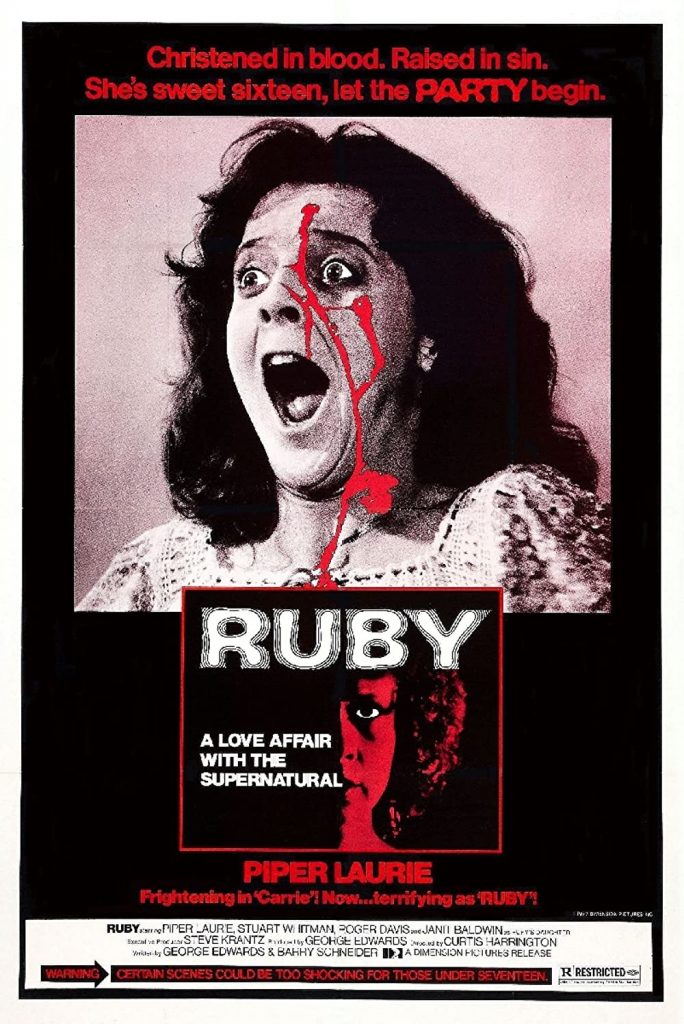

From there, she went to New York City to study acting, and worked on live television, starring in The Hallmark Hall of Fame version of “Twelfth Night” (1957), “The Days of Wine and Roses” (1958) with Cliff Robertson, which debuted on Playhouse 90 on October 2, and as “Kirsten” in the Playhouse 90 version of “Winterset” (1959). In 1961, she got the part of Paul Newman‘s crippled girlfriend in the classic film, The Hustler (1961). She was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress for that role of “Sarah Packard”. That same year, she was interviewed by a writer/reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, Joe Morgenstern. She liked his casual dress and lifestyle and, 9 months later, they were married. When she did not receive any substantial acting offers after The Hustler (1961), she retreated with her husband to Woodstock, New York, where she pursued domestic activities such as baking (her grandfather’s trade) and raising her only daughter, Anne, born in 1971. In 1976, she accepted the role of “Margaret White”, the eccentric religious zealot mother of a shy young psychic girl named Carrie (1976), played by Sissy Spacek. Piper received her second supporting Oscar nomination for this role. She and her husband divorced in 1981, she moved to Southern California and obtained many film and television roles.

She got a third Oscar nomination for her role as “Mrs. Norman” in Children of a Lesser God (1986), and won an Emmy that same year for her acting in Promise (1986), a television movie with James Garner and James Woods. She has appeared in more than 60 films, from 1950 to the present. Ms. Laurie has appeared in many outstanding television shows from “The Best of Broadway” in 1954, to roles on “Playhouse 90” in 1956, roles on St. Elsewhere (1982), Murder, She Wrote (1984), Matlock (1986), Beauty and the Beast (1987), ER (1994), Diagnosis Murder (1993) and Frasier (1993). Her daughter, Anne Grace, has made her a grandmother, and though she lives in Southern California, she frequently visits her daughter in New York.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: garyrick96@hotmail.com

Piper Laurie passed away in October 2023 at the age of 91.

The above iMDB entry can also be accessed online here.

Variety obituary in October 2023:

Piper Laurie, who blossomed as an actress only after extricating herself from the studio system and went on to rack up three Oscar nominations, has died. She was 91.

Laurie’s manager Marion Rosenberg confirmed the news to Variety, writing, “A beautiful human being and one of the great talents of our time.”

Laurie scored her first Oscar nomination for her work opposite Paul Newman in 1961’s classic poolhall drama “The Hustler,” in which she played an alcoholic who memorably tells Newman’s character, “Look, I’ve got troubles and I think maybe you’ve got troubles. Maybe it’d be better if we just leave each other alone.”

Getting Marvel TV a Rewrite Was Overdue

Though she informally retired to raise a family for more than a decade, she returned to film and television in the mid-’70s and racked up an impressive roster of characterizations, including Oscar-nominated turns in “Carrie” and in “Children of a Lesser God,” in which she played Marlee Matlin’s icy mother. Laurie was truly chilling in “Carrie,” as the mother of the shy telekinetic girl of the title who has, in the words of Roger Ebert, “translated her own psychotic fear of sexuality into a twisted personal religion.”

Her performance as the plotting, power-hungry Catherine Martell in David Lynch’s landmark TV series “Twin Peaks” brought her two of her nine Emmy nominations. The actress won her only Emmy for her role in the powerful 1986 “Hallmark Hall of Fame” entry “Promises,” in which James Wood starred as a schizophrenic and James Garner as his brother, with Laurie’s character offering help to the pair.

She scored her last Emmy nomination in 1999 for a guest role on sitcom “Frasier” in which she played the mother of a radio psychologist played by Christine Baranski and clearly modeled after Dr. Laura Schlessinger.

The actress negotiated herself out of her contract with Universal in the mid-’50s after a series of ingenue roles in mediocre films and turned in an impressive supporting performance in Robert Wise’s “Until They Sail” (1957), with Jean Simmons, Paul Newman and Joan Fontaine.

She then headed east; in New York she appeared in television productions of “Twelfth Night” and “Caesar and Cleopatra.” She picked up Emmy nominations for original drama “The Deaf Heart” on “Studio One in Hollywood” and “Days of Wine and Roses” with Cliff Robertson on “Playhouse 90.” Director Robert Rossen spotted her working at the Actors Studio and offered her the role of the crippled alcoholic Sarah Packard in the drama “The Hustler,” which brought her an Oscar nomination as best actress in 1961.

Soon thereafter she married writer Joseph Morgenstern, later a film critic, and left show business to start a family, living in Woodstock, N.Y.

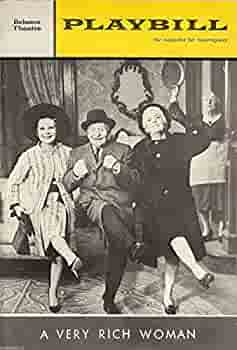

By the mid-’70s she was ready to work again and appeared in a Broadway revival of “The Glass Menagerie” and in an episode of PBS’ “Nova” science series as pioneer family planning champion Margaret Sanger.

Laurie took Brian De Palma’s “Carrie” almost as a lark. But her tongue-in-cheek but terrifying performance in the horror film brought her a second Oscar nomination in the supporting category. She followed that up with an Australian drama “Tim,” starring a young Mel Gibson, as well as films including “Ruby,” “The Boss’s Son” and “Return to Oz.”

She also began regular work on television in such TV movies as “In the Matter of Karen Ann Quinlan”; the Judy Garland biography “Rainbow”; 1981’s “The Bunker,” in which she played Magda Goebbels to Anthony Hopkins’ Hitler, drawing an Emmy nomination; “The Thorn Birds,” which brought her another Emmy nom; and 1986’s “Promise,” for which she won an Emmy for supporting actress. She was also guesting on TV series, picking an Emmy nom in 1984 for her work on “St. Elsewhere.”

Bigscreen work during the late ’80s and ’90s included “Appointment With Death,” “Other People’s Money,” “Wrestling Ernest Hemingway,” “Storyville,” “Rich in Love,” and “The Crossing Guard.” In the well-regarded period dramedy “The Grass Harp,” she reunited with her “Carrie” co-star Sissy Spacek but this time played her sister (they also both appeared in the 2001 telepic “Midwives”).

In the 1990s and 2000s she guested on the likes of “ER,” “Diagnosis Murder,” “Touched by an Angel,” “Will and Grace” and “Law and Order: SVU.” She appeared steadily in a series of telepics.

Her last film appearances included “Eulogy” (2004), in which she stood out as the matriarch of a dysfunctional family; “The Dead Girl,” in which she played another cruel mother, this one bed-ridden; “Hounddog,” as the stern grandmother of rape victim Dakota Fanning; and “Hesher,” in which she memorably shared a bong with the stranger, played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, who insinuates himself into her household.

Born Rosetta Jacobs in Detroit on Jan. 22, 1932, she was plucked out of Los Angeles High School at age 17 and signed to a Universal contract for $250 a week, which would run up to $1,750 a week after seven years.

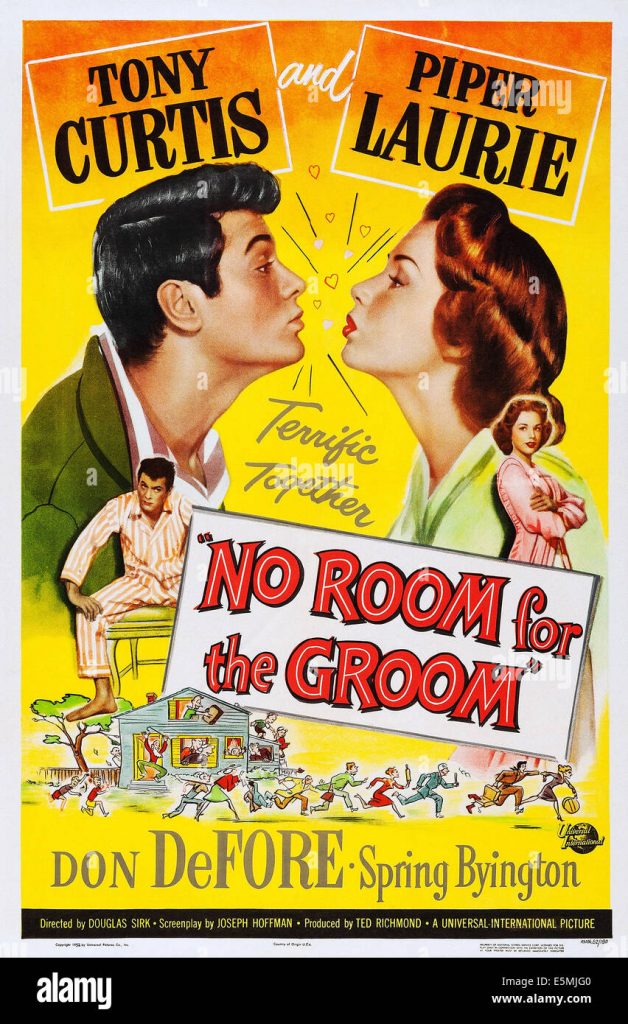

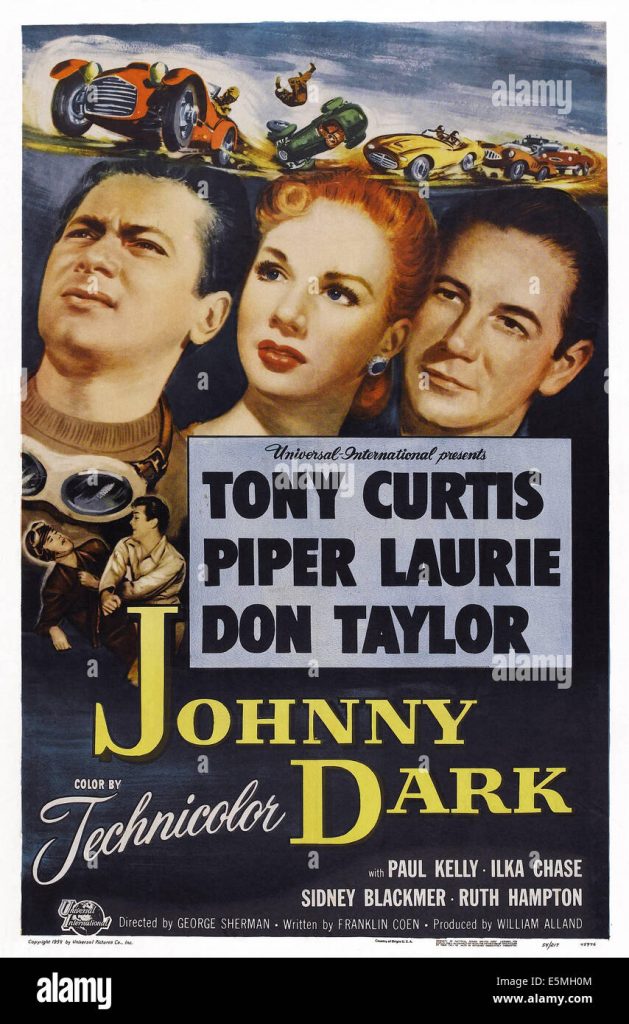

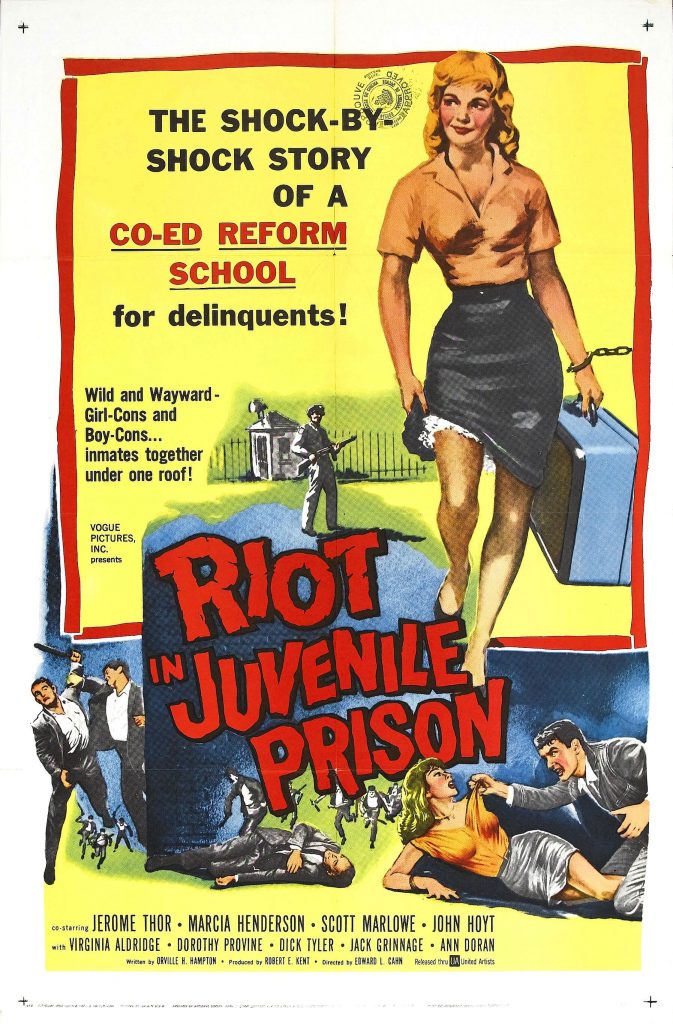

She made her debut as Ronald Reagan’s daughter in the 1950 film “Louisa” and then went on to star in a series of undistinguished comedies and musicals, including a foray into the Francis the talking mule series called “Francis Goes to the Races.” As an ingenue she was the love interest of such up-and-comers as Tony Curtis and Rock Hudson and established stars including Tyrone Power and Victor Mature.

Among the early forgettable films were “Johnny Dark,” “Dangerous Mission,” “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “No Room for the Groom.”

“I hated what I was doing,” she later told a journalist. But she also admitted that the regular work helped her develop and move on to more gratifying projects.

Laurie and Morgenstern divorced in 1981. She is survived by a daughter, Anne Grace