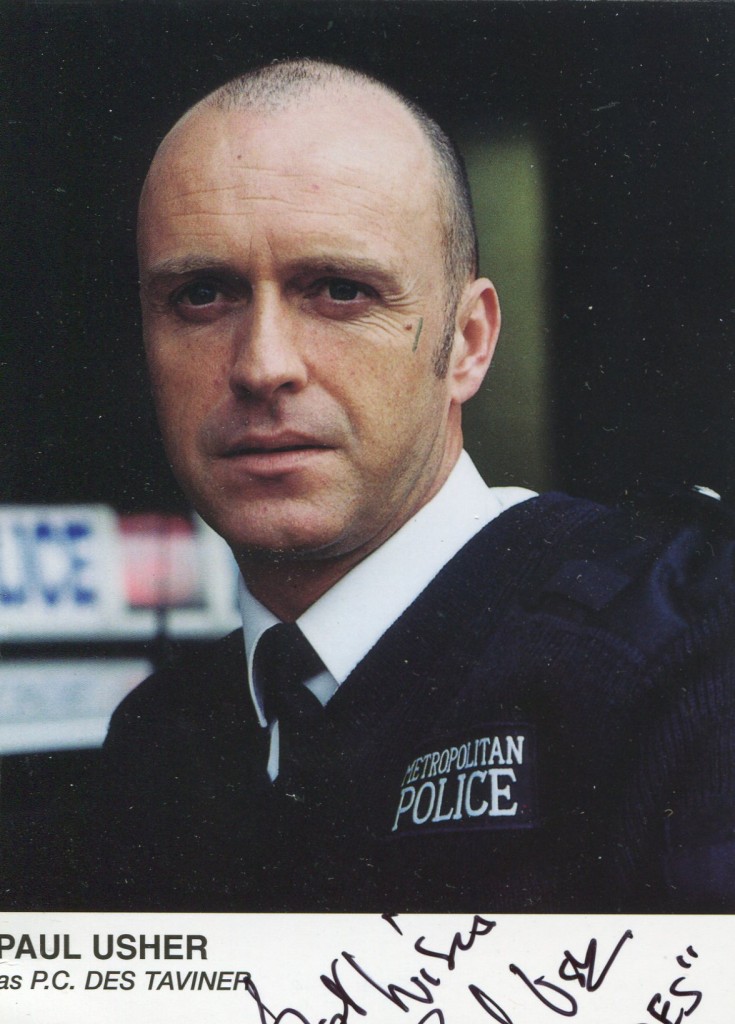

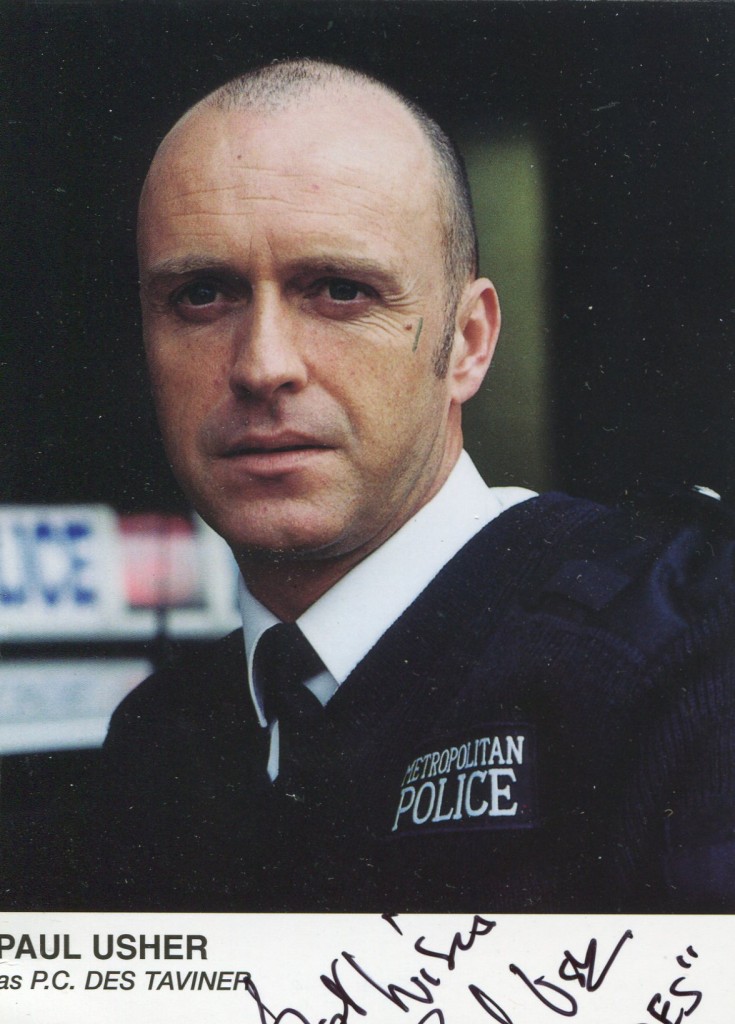

Paul Usher was born in Liverpool in 1961. He is pri marily known for is role in “The Bill” as OC Des Taviner. His other credirs include “Swing”, “Liverpool 1” and “Robin Hood”.

Brittish Actors

Paul Usher was born in Liverpool in 1961. He is pri marily known for is role in “The Bill” as OC Des Taviner. His other credirs include “Swing”, “Liverpool 1” and “Robin Hood”.

Eddie Calvert was a very famous trumpeter in the 1950’s. He had two hughly popular hits “O My Papa” and “Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White”. He did feaure in the film “Beyond Mombasa” in 1956 with Cornel Wilde and Donna Reed. Eddie Calvert died in Salsbury, Rhodesia in 1978 at the age of 56.

His “Wikipedia” entry:

Calvert was born in Preston, Lancashire, England,[3] and grew up in a family where the music of his local brass band featured highly. He was soon able to play a variety of instruments, and he was most accomplished on thetrumpet.[3] After World War II he graduated from playing as an amateur in brass bands to professional engagements with popular dance orchestras of the day, including Geraldo’s plus Billy Ternet,[3] and he soon became renowned for the virtuosity of his performances. Following his exposure on television with the Stanley Black Orchestra, an enthusiastic announcer introduced him as the ‘Man With The Golden Trumpet’ – an apt description that remained with him for the rest of his musical career.

Calvert’s style was unusually individualistic, and he became a familiar musician on BBC Radio and TV during the 1950s. He first recorded for Melodisc, ca 1949-1951 before he started to record for the Columbia label and hisrecords included two UK number ones, “Oh Mein Papa” and, more than a year later, “Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White“. He was the first British instrumentalist to achieve two number ones. “Oh Mein Papa” which also sold well in the United States, topped the UK Singles Chart for nine weeks (then a UK chart record), and he received the first gold disc awarded for a UK instrumental track.

Further chart entries were “John And Julie”, taken from the soundtrack of the movie John and Juliet, and “Mandy”, his last major hit. Other recordings included “Stranger In Paradise” (1955), “The Man with the Golden Arm” (1956) and “Jealousy” (1960). Calvert co-wrote the song “My Son, My Son“, which was a hit for Vera Lynn in 1954. In spite of being an instrumental, his theme music for the film The Man with the Golden Arm was banned by the BBC “due to its connection with a film about drugs”.[4]

In 1960 he was invited by orchestra leader, Norrie Paramor and their mutual friends Ruby Murray and Michael Holliday to record an extended-play single with four tracks. Calvert played Silent Night and on another track he, Murray and Holliday teamed up in a version of Good Luck, Good Health, God Bless You. The single, released by Columbia Records achieved some success in Britain but was more popular in Australia and South Africa.

As music began to change in the 1960s with the worldwide popularity of groups like The Beatles and the rock n’ roll genre, Calvert’s musical renditions became less popular among record buyers. By 1968 Calvert had become disillusioned with life under the Labour government of Harold Wilson and was especially critical of London’s policy towards Rhodesia. After a world tour that included several stops in Africa, he left the UK, making South Africa his home. He continued to perform there, and was a regular visitor to Rhodesia. He continued to record for the local market and performed a version of “Amazing Grace“, retitled “Amazing Race” specially adapted for Rhodesia.[5]

On the 7 August 1978, Calvert collapsed and died of a heart attack in the bathroom of his home in Rivonia, Johannesburg. He was fifty-six years old.

The above “Wikipedia” entry can also be accessed online here.

Janet McTeer was born in 1961 in Newcastle-on-Tyne. She made her movie debut in 1986 in “Half Moon Street”. In 1997 she won a Tony Award on Broadway for her performance in “Hedda Gabler”. Two years later she was nominated for an Oscar for her performance in “Tumbleweeds”. She filmed “Albert Nobbs” in Dublin with Glenn Close.

TCM Overview:

Equally at home on stage or on camera in both period pieces and modern dramas, actress Janet McTeer proved to be one of the more versatile actresses to cross over from the U.K. to Broadway and American film. Having made a name for herself on the stages of London and on British television, McTeer found her breakout role when she was cast as Nora in a West End revival of Henrik Ibsen’s “A Doll House” in 1996. The lauded production’s move to Broadway the following year not only won the actress multiple awards, including a Tony, but also led to her being cast as the lead in the independently produced drama “Tumbleweeds” (1999), which earned her a Golden Globe. Another winning role came with the Sundance Film Festival favorite “Songcatcher” (2001), followed by turns in the Terry Gilliam-directed “Tideland” (2005) and such acclaimed miniseries as “Five Days” (BBC1, 2007) and “Into the Storm” (HBO, 2009). After earning more raves on Broadway in mountings of “Mary Stuart” and “God of Carnage,” the actress stunned audiences and critics alike with her convincing portrayal of a woman posing as a man in Victorian-era London opposite Glenn Close in “Albert Nobbs” (2011). Undeniably talented and exceptionally adaptable, McTeer had rightfully earned her reputation as one of the most dependable actresses on either side of the pond.

McTeer was born May 8, 1961 in the Northeastern England city of Newcastle. Despite never having been on a stage during her youth, McTeer auditioned and was accepted into the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts immediately following high school. She made her London stage debut in 1985 with an Olivier Award-nominated performance in the title role of “The Grace of Mary Traverse,” and went on to build a résumé at the Royal Exchange Theater in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” “The Storm” and “Greenland.” Meanwhile, McTeer landed a few guest appearances in TV dramas and made her film debut in a small role as a secretary in the thriller, “Half Moon Street” (1986), starring Michael Caine and Sigourney Weaver. McTeer continued to build the resume with a prominent role in a TV comedy set at a modeling agency called “Les Girls” (ITV, 1988), and delivered an outstanding turn when cast against type as the clumsy, unsure Hazel in Robert Ellis Miller’s “Hawks” (1988). In a memorable starring turn, McTeer starred as an outcast-turned-heroine in rural 19th Century England in “Precious Bane” (PBS, 1989), based on the novel by Mary Webb.

Making her first significant big screen impression, McTeer enjoyed a sizable film role as Ellen Dean in the uneven 1992 remake of “Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights,” starring Juliette Binoche and Ralph Fiennes. She etched a memorable, feisty Vita Sackville-West in the 1990 BBC TV production, “Portrait of a Marriage” (PBS, 1992), and continued to appear on American television in British drama imports like “102 Boulevard Haussmann” (A&E, 1991) and “The Black Velvet Gown” (PBS, 1993). She was nominated again for an Olivier Award for playing Yelena in a 1992 London production of “Uncle Vanya” before returning to British television to star as a disliked prison matron set on rebuilding a facility nearly destroyed by riots in the series, “The Governor” (YTV, 1995-96). Continuing to alternate between stage and screen, McTeer made a spirited Beatrice in a West End production of “Much Ado About Nothing,” prior to being cast opposite Emma Thompson and Jonathan Pryce in “Carrington” (1995), about British painter and member of the fame Bloomsbury artist colony, Dora Carrington.

That film won a Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and McTeer scored another victory on the London stage with her portrayal of unsatisfied housewife Nora in Henrik Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House.” Although the 6’1″ actress initially considered herself too tall to play Nora – a character often referred to as “petite” – McTeer flew in the face of convention and attacked the role with a vengeance, refusing to reduce her heroine to a proto-feminist, and bringing out all Nora’s confusion, pain, and prodigious sexuality. The highly animated performance earned her an Olivier Award for her London run and Tony Award, Drama Desk, and Theater World Awards on her subsequent Broadway sweep. This highly visible success also helped launch McTeer’s international movie career. In short order, she was tapped to provide the narration for Todd Haynes’ “Velvet Goldmine” (1998) and to star in the indie drama “Tumbleweeds” (1999), as the peripatetic single mom of a 12-year-old girl. For her powerful portrait of a mother-daughter relationship, McTeer earned a Best Actress Oscar nomination and a Golden Globe win.

In her big screen follow-up, McTeer headlined the Maggie Greenwald film, “Songcatcher” (2001), portraying a turn of the century musicologist who travels to the Appalachian Mountains where she discovers and documents the region’s largely unknown music culture. That film won a Special Jury Prize at Sundance and McTeer lingered on the American independent film scene to play opposite Billy Crudup in the romantic thriller, “Waking the Dead” (2000). McTeer hit the international film festival circuit with “The King is Dead” (2002), in which she played one of a bus full of tourists stranded in a remote African desert who stage a production of King Lear to pass the time, only to have the play mirror their own character flaws and fight for survival. In 2004, the actress co-wrote and starred in ”The Intended” as one-half of a British couple stationed in the Malayan jungle to work in the 1920s ivory trade. The heavy melodrama did little to excite critics or draw audiences and McTeer returned to the small screen with a supporting role in “Miss Marple: The Murder at the Vicarage” (PBS, 2004-05).

In 2006, McTeer had a supporting role in Terry Gilliam’s nearly universally panned childhood fantasy, “Tideland” (2006), and starred on the London stage as a uncompromisingly nonconformist Mary Queen of Scots in a revival of the 1800 drama, “Mary Stuart.” She was also cast in the British drama series, “The Amazing Mrs. Pritchard” (BBC1, 2006) as a conservative politician who becomes an ally to the title character, a supermarket clerk (Jane Horrocks) whose populist outcry leads her to be elected Prime Minister of Britain. McTeer’s television career continued to strengthen, with her leading role opposite Hugh Bonneville as a street-smart detective investigating the disappearance of a mother and two children in the HBO/BBC co-produced miniseries, “Five Days” (BBC & HBO, 2007).

McTeer appeared on the West End in 2008 in the comic “Gods of Carnage,” and played Mrs. Dashwood in a BBC TV production of Jane Austen’s “Sense and Sensibility” (BBC, 2008). Early the following year, McTeer reprised her role in the “Five Days” sequel, “Hunter” (BBC1, 2009). Returning Broadway, McTeer reprised her acclaimed take on Mary Queen of Scots in “Mary Stuart,” earning a Tony nomination for Best Actress in a Play and taking home a Drama Desk Award. The same year, she earned an Emmy nomination for her supporting role as Clemmie Churchill, wife of Sir Winston (Brendan Gleeson), in “Into the Storm” (BBC & HBO, 2009), HBO’s miniseries focused on Churchill during World War II. McTeer’s performance earned the actress a Golden Globe nomination for Best Supporting Actress.

Following another successful run on Broadway in “God of Carnage” in 2009, McTeer continued to impress, even in little-seen efforts such as the action-adventure “Cat Run” (2011), in which she played a matronly assassin-for-hire. Theatrically released only in the United Kingdom, “Island” (2011) was an intense drama featuring McTeer as a mother who, after abandoning her child at birth, is confronted by the angry daughter (Natalie Press) decades later. The actress once again garnered acclaim for her performance in “Albert Nobbs” (2011) as a woman masquerading as a man in order to gain employment in 19th century England. Her work in the film, co-written by and starring Glenn Close in the title role – as a woman harboring a similar secret identity – garnered McTeer both Oscar and Independent Spirit Award nominations for Best Supporting Actress.

James Hayter was a British character actor with a very distinctive voice. He was born in 1907 in India. He trained at RADA and made his film debut in 1936 in “Sensation”. Other films in which he was featured include “Captain Boycott”, “The October Man”, “My Brother Jonathan” and”The Fallen Idol”. He was part of the cast of “Are You Being Served”. James Hayter died in 1983.

His IMDB entry:

The son of a police superintendent in India, the character actor James Hayter was educated in Scotland, where he was urged into acting by his headmaster. After one year (1924-5) at the Royal Academy of the Dramatic Arts in London, he performed in repertory theater, eventually appearing in The West End in such plays as “1066 and All That” and “French Without Tears.” He made his film debut in 1936 and continued in films until World War II, when he served in the Royal Armoured Corps. After the war, he established an active screen career, excelling at various sorts of character roles, especially in comedy. Characteristic roles include Friar Tuck in The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952) and A Challenge for Robin Hood (1967), The Pickwick Papers (1952), andDavid Copperfield (1969).

Elspeth March was born in 1911 in London. She made her movie debut in 1939 in “Caesar’s Friend”. Her other films include “The Boys in Brown” in 1949, “Quo Vadis”, “The Miracle”, “Midnight Lace” with Doris Day made in Hollywood and in 1961 “The Playboy of the Western World” with Siobhan McKenna and Gary Raymond. Elspeth March died in 1999 at the age of 88.

Alan Strachan’s obituary of Elspeth March in “THe Independent”:

March also enjoyed the very best years of the British repertory system, with the kind of career denied young actors today, playing an enormous variety of roles in a crucial early period at the Birmingham Rep at one of its highest points.

Later in her career, with her formidable stage presence, commanding eyes and expressively wide-ranging voice, she was much in demand as a valued supporting character actress, playing a good number of battle-axes and dragonesses, often with whiplash comic precision, more than occasionally enlivening some less than effervescent scripts.

Her career never quite flowered as it should have; she never had the luck to play some parts for which she would have been ideal – Lady Bracknell or a number of Restoration comedy’s gallery of deluded dowagers – and poor health clouded her later years. At her peak, however, she was one of the most distinctive, stylish actors of her generation.

Born Elspeth Mackenzie into the comfortable world of a military family and given an excellent education at Sherborne School for Girls in Dorset, she gravitated early to the stage, and after her Central School training and a first professional appearance in a tiny part in Jonah and the Whale (Westminster Theatre, 1932) she played a few more minor roles and understudied in the West End until she was offered a season at the Birmingham Rep.

Between 1934 and 1937 she had a glorious run of rewarding leading roles there including the title role in Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan and Elizabeth in Rudolf Besier’s 1930s smash-hit The Barretts of Wimpole Street. She also appeared at the Malvern Festivals between 1935 and 1937 when Shaw himself was often in evidence and in charge.

Her attack and vocal variety were supremely suited to Shaw and her many Shavian roles at Malvern included the rarity of Vashti in The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles, the rebellious Hypatia in Misalliance, Miss Brollikins in the political satire On the Rocks, the enormously demanding vocal pyrotechnics and physical agility of Epifania in The Millionairess, and Orinthia the seductive royal mistress in The Apple Cart.

More unexpectedly – although discerning directors had noted her versatility – she had a great personal success as The Widow Quin in Synge’s Playboy of the Western World (a Mercury Theatre production, later transferring to the Duchess, in 1939) and she also played the part equally successfully nearly 20 years later for the Irish Players in New York (Tara Theatre, 1958).

While at Birmingham in the mid-1930s March had met fellow actor Stewart Granger. They married in 1938 and the following year performed together in a number of plays in Aberdeen, including Arms and the Man and Hay Fever (Michael Denison and Dulcie Gray performed the juvenile roles).

During the Second World War, rather than join Ensa, March left the stage for nearly five years to serve as a driver for the American Red Cross. Her immediate post-war career was unsettled, with some unrewarding roles and some disappointing London productions, although Noel Coward’s large- cast Peace in Our Time (Lyric, 1947), set in a London pub against the background of an imagined 1940-45 Britain under Nazi occupation, gave her a meaty part as a novelist whose son has been killed in the Battle of Britain (Coward admired both her performance and the quality she maintained throughout the run).

She also had a happy return to Shaw with a much-praised Ftateeta in the Olivier/Vivien Leigh production of Caesar and Cleopatra (St James’s, 1951) for the Festival of Britain. During the 1950s, good parts continued to be frustratingly sporadic following the break-up of her marriage to Stewart Granger, who had become a major movie star.

Even if some of her later performances were in productions which failed to reach London, March at least occasionally had the consolation – important, to one so well-read herself – of appearing in some work of distinguished pedigree. At the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre in Guildford in 1966 she played the relatively small but pivotal role of Maria, a handsomely enigmatic woman who enters as the fiancee of a newly enriched Edwardian bachelor gentleman only to become the wife of his recently bereaved brother, in Julian Mitchell’s subtle distillation of Ivy Compton-Burnett’s lethally mordant portrait of family spites and tensions in A Family and a Fortune.

Also at Guildford (1967) she was glittering as the doctor hero’s mother in Tennessee Williams’s Eccentricities of a Nightingale (a reworking of Summer and Smoke), and she toured in Rodney Ackland’s masterpiece maudit The Dark River.

Never one to be fazed by the seesaw vagaries of a theatrical career, she enjoyed her surprisingly long run in Ronald Millar’s piece of medieval pish-tushery Abelard and Heloise (Wyndham’s, 1970) as a severely wimpled Abbess just as much as her very much shorter run in the same author’s sprawling generation-gap flop Parents’ Day (Globe, 1972).

One of her most memorable later appearances was in a dire West End comedy written as a vehicle for Maggie Smith’s then somewhat baroque comic technique. Snap (originally titled Clap, Vaudeville, 1974) was a kind of modern-day La Ronde set in a Bohemian fashionable London involving most of its characters in a chain of sexually transmitted diseases. Time has mercifully obliterated the memory of most of the details of this hapless piece – directed, amazingly enough, by William Gaskill – but not that of Elspeth March as Maude, a barking vision in heavy tweeds, up in London from her country retreat (nudgingly named Radclyffe Hall) and hilariously aghast at the ways of this new-age Sodom.

Elspeth March also had a long and successful television and film career, starting with Mr Emanuel (1944), and helped to enliven the dim musical re-make of Goodbye, Mr Chips (1969). A woman of great taste and strong loyalties, she was a genuinely generous personality with a very wide circle of family and friends.

Elspeth Mackenzie (Elspeth March), actress: born London 5 March 1913; married 1938 Stewart Granger (died 1993; one son, one daughter; marriage dissolved 1948); died London 29 April 1999.

The above obituary can also be accessed online here.

IMDB Entry:

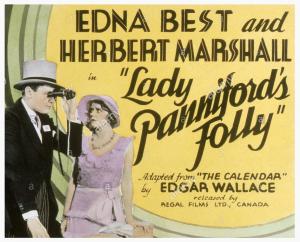

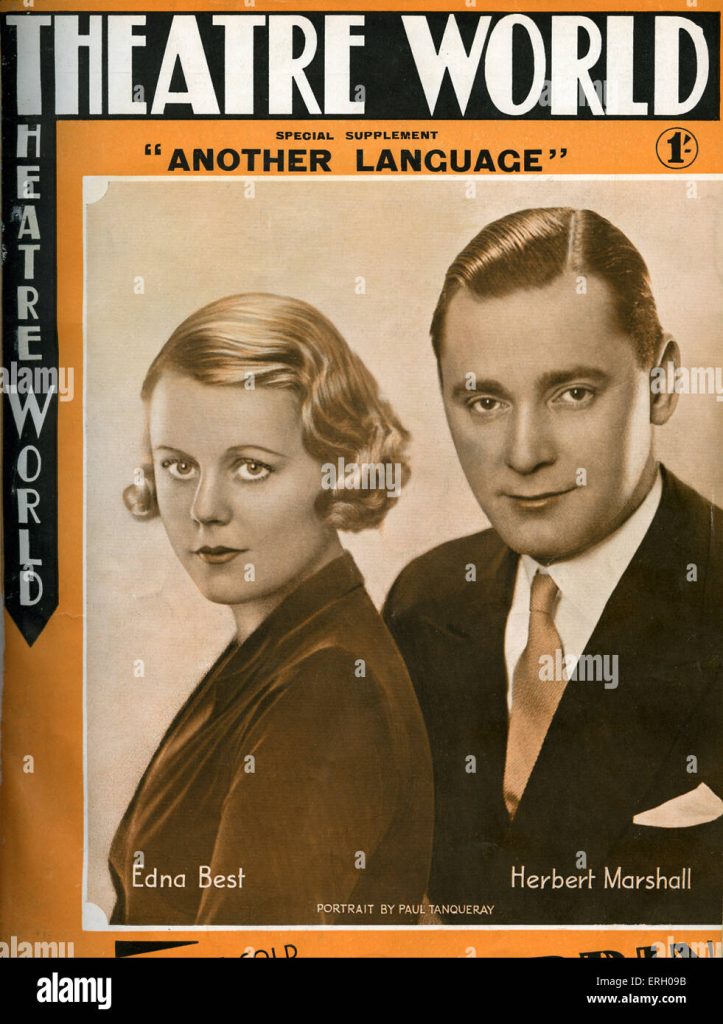

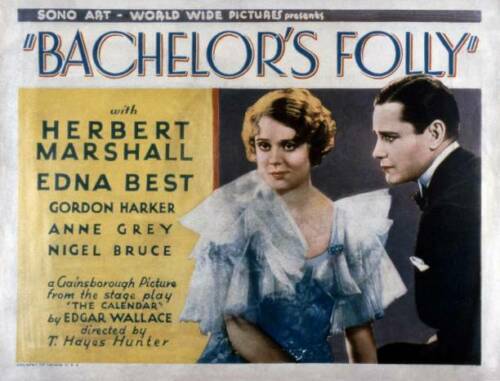

Genteel, lady-like British actress who was a much respected theatrical star in the 1920’s and 30’s, both in her own country and in the United States. Born in Hove, Sussex, in March 1900, she took to the stage at the age of seventeen, as Ela Delahay in ‘Charley’s Aunt’. She played Peter Pan three years later and married the first of her actor husbands, Seymour Beard. By the mid-1920’s, Edna had become the toast of London for her performances in ‘Fallen Angel’ (with Tallulah Bankhead), and, a role she made her own, as Teresa (Tessa) Sanger, in ‘The Constant Nymph’ (opposite Noel Coward and, later,John Gielgud). With the part of Tessa, she also enjoyed a successful run on Broadway in 1926, which was followed by another Margaret Kennedy play, ‘Come With Me’. She married her co-star, Herbert Marshall after divorcing Beard in 1928.

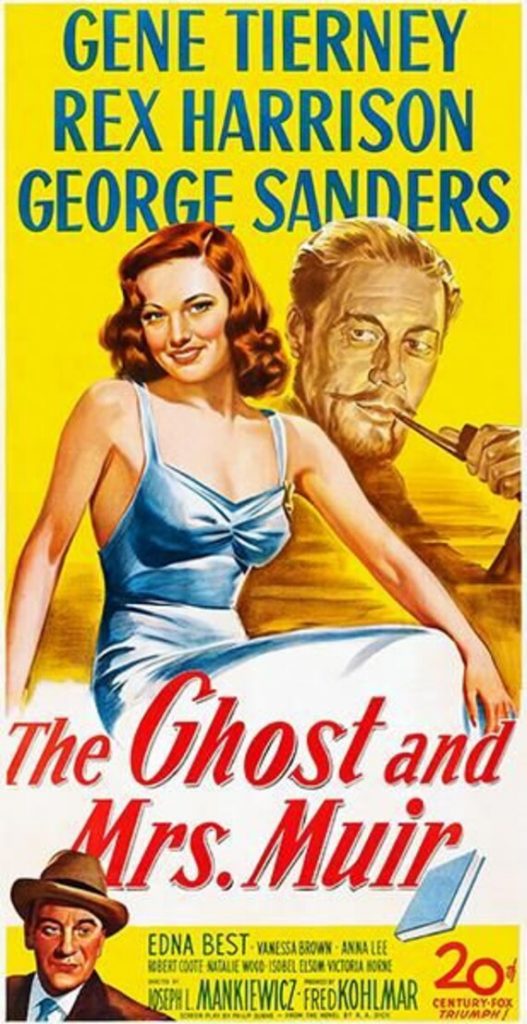

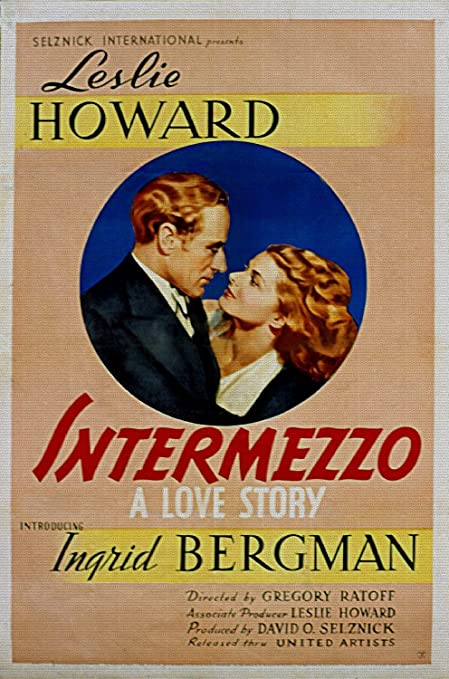

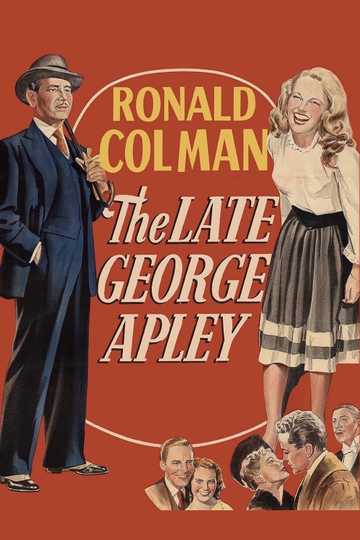

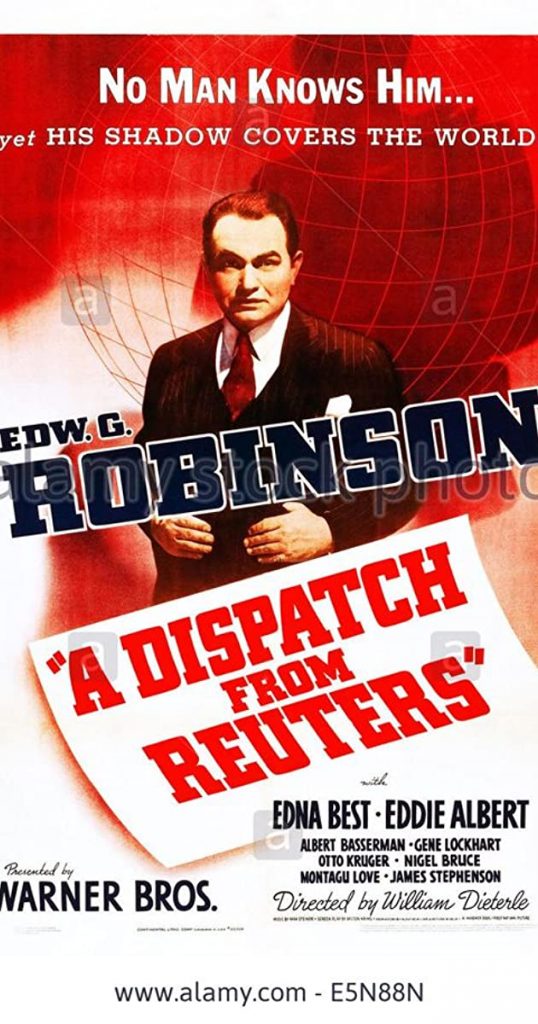

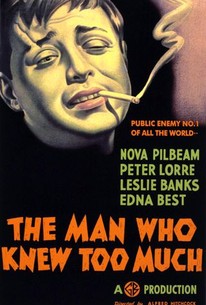

Edna started in films as early as 1921, but made little headway until Michael and Mary(1931), in which she recreated her role from the London stage. She then co-starred again with husband Herbert Marshall in Faithful Hearts (1932), but neither of these films received much international exposure. Her only Hollywood film at this time was The Key(1934), which, though directed by Michael Curtiz, was ,alas, ‘low-key’ as far as critical plaudits or box office were concerned. She had smallish parts in other British films, South Riding (1938), and the original version of Alfred Hitchcock‘s The Man Who Knew Too Much(1934), as the mother of kidnapped Nova Pilbeam. Not until 1939, did a worthy motion picture role come her way in the shape of the forlorn wife, whom violinist Leslie Howarddeserts for Ingrid Bergman in Intermezzo: A Love Story (1939). Other noteworthy screen roles were her Catherine Apley in The Late George Apley (1947), and the housekeeper Martha of The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) which the New York Times review of June 27 considered ‘by far the best performance’ in the picture. Edna’s film appearances were few and far between, and only a handful adequately showcased her talents as an actress, which are so abundantly evident from the body of her work in the theatre.

BFrom 1939 a U.S. resident and a nationalised citizen by the early 1950’s, Edna continued her frequent triumphant returns to the stage. Her most celebrated performances on Broadway were in Terence Rattigan‘s ‘The Browning Version’, as downtrodden housewife Millie Crocker-Harris, and ‘Harlequinade’ (1949), both co-starring Maurice Evans; and as the titular character ‘Jane’ (1952), a play adapted by S.N. Behrman from a W. Somerset Maugham short story. Brooks Atkinson described her performance as the timorous spinster as both ‘comic’ and ‘forceful’. In her last significant role on stage, she co-starred with Brian Aherne and Lynn Fontanne in the romantic comedy ‘Quadrille’ (1954-55), directed by Alfred Lunt and outfitted by Cecil Beaton, who also designed the costumes. Edna retired from acting in the early 1960’s and died in a clinic in Geneva, Switzerland in 1974.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: I.S.Mowis

The above IMDB entry can also be accessed online here.

Ernest Clark was born in 1912 in London. He made his film debut in “Private Angelo” in 1949. His many films include “The Mudlark”, “Doctor in the House”, “Father Brown”, “A Tale of Two Cities” and “No Love for Johnnie”. He starred in the Doctor series based on Richard Gordon’s books from 1969. Ernest Clark was married to Julia Lockwood the actress daughter of Margaret Lockwood. He died in Somerset in 1994.

Eleanor Summerfield was a stalwart character actress who was very profilic in British films in the 1940’s and 50’s. She made her film debut in 1947 in “Take My Life”. Her other films include “Laughter in Paradise”, “Scrooge”, “The Last Page”, “Mandy”, “Street Corner”, “Lost” and “A Cry From the Streets”. She was married to actor Leonard Sachs and is the mother of actor Robin Sachs. Eleanor Summerfield died in 2001 at the age of 80.

“Guardian” obituary:

Film, theatre and television actor as adept at drawing tears from her audience as laughs

Eric Shorter

The actor Eleanor Summerfield, who has died aged 80, shed some early comic light on the earnest, dark and intellectually pretentious plays of the postwar poetic revival in London theatre. While the fashion for verse drama was later to bring Edith Evans in Christopher Fry’s The Dark Is Light Enough, Laurence Olivier in that author’s Venus Observed and Alec Guinness in TS Eliot’s The Cocktail Party, in 1945 E Martin Browne was still struggling to re-establish the movement at the tiny Mercury Theatre in Notting Hill. For audiences and critics alike, trying to fathom the meaning of Ronald Duncan’s masque and anti-masque in verse called This Way to the Tomb! (which the critic James Agate sneeringly retitled Turn Right for the Crematorium) was no joke.

With such “types” on stage as the Man of Culture, the Mobile Worker, the Announcer to the Astral Group, the Postcard Seller and an Old Man, it was the Girl of Leisure who caught the eye: a tallish, blue-eyed blonde with quizzical, soaraway eyebrows. Here was an apparently natural comedienne, and when Duncan’s symbolic novelty with music by Benjamin Britten transferred to the West End, Eleanor Summerfield took a second role – that of Lechery. By then, Browne had found another dramatist-in-verse and another role for Summerfield – Lil in Anne Ridler’s The Shadow Factory – but it was as Doto in Christopher Fry’s A Phoenix Too Frequent that the actor came to pro The Fry one-acter was set, characteristically, in an underground tomb near Ephesus, where a widow proposes to mourn her dead husband by fasting to death. Doto seems ready to follow her mistress to the grave, except that after a while – and a lot of hazy chit-chat – she finds herself doting not on her late master but on living men.

While Fry took credit for his wry little joke, the audience took away a vivid memory of Summerfield the comedienne. Her acting was likened by one critic to a “slightly distorted Greek vase painting”; for another she proved a “most absurd and cheerful companion”. Cheer and absurdity went on to amuse – and sometimes amaze – audiences for the rest of Summerfield’s career in television, cinema, theatre and radio. Unsurprisingly, once her comic instinct had been confirmed, the Rada-trained Summerfield turned away from verse drama towards the kind of verse that began to flourish at what became her spiritual home, the Players’ Theatre Club, beneath the arches at Charing Cross. There, verse was not only sung, but also came in rhyming couplets in homage to Queen Victoria and the music hall. Summerfield was to marry the man who ran the place, Leonard Sachs, later known to television audiences as chairman of The Good Old Days. Although Summerfield never left the theatre, it was to be another 40-odd years before the classical stage realised what a talent it had lost. It wasn’t until 1989, as Lady Wishfort in Congreve’s The Way of the World for the Cambridge Theatre Company at the Young Vic, that her theatrical talent proved itself again. Instead of playing Wishfort as the comically raddled and randy old thing from a saucy seaside postcard, Summerfield made her ruefully self-aware, even to the point of pathos.

In most of her feature films, Summerfield came on as the light relief – the comic mother or the woman next door or the woman you could never get away from; and though at first television used her in the same spirit, she broke free, after a while – she said it took 40 plays – from typecasting. When, in 1956, she won a News Chronicle poll for readers’ favourite actresses, Summerfield complained that the BBC had never let her be anything other than a funny creature in one low comedy after another, while independent television had given her a chance to prove herself an all-rounder “who can make ’em cry all the better for having made them laugh the week before”.

Among these television credits were My Wife’s Sister, Down Came a Blackbird, The Two Charlies, Night Train to Surbiton, David Copperfield and The World of Wooster. Summerfield also enjoyed panel games such as Many a Slip, chaired by Roy Plomley, which lasted more than 15 years on Radio 4. Of the rest of her stage work, one might pick out her “delightful artifice and delicious aplomb” in a French marital comedy, Gooseberry Fool (Duchess, 1949) or, 10 years later, her vivacious fooling in an otherwise uninspiring Italian-type musical with Dickie Henderson and Frank Leighton, When In Rome . . . (Adelphi, 1959). Or, at the same theatre nine years earlier, something called Golden City. This was the extravagant heyday of London musical comedy, when a cast of 60 was normal. Set in South Africa during a 19th-century gold rush, John Tore’s show included a war dance choreographed by Robert Helpmann, but its treasure was Summerfield as strolling player from Victorian variety (echoes of her work at the Players’ Theatre). Amid the din, she had the hit song. With it she stilled the house – What More Is There to Say? was the title. Of Summerfield’s performance the stately critic JC Trewin wrote: “She is an artist.”

Leonard Sachs died in 1990. Eleanor Summerfield is survived by her two sons, Toby and Robin.

Eleanor Summerfield, actor, born March 7 1921; died July 13 2001.

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

Patricia Plunkett was born in London in 1926. Her first film was “It Always Rains on Sundays” in 1847 with Googie Withers. Her other films include “Landfall”, “Bond Street”, “Mandy”, “The Crowded Day”, “Dunkirk” and “The Singer Not the Song”. She died in 1974 at the age of 47.

Anyone who knows me are aware that I am a bit of a movie buff. Over the past few years I have been collecting signed photographs of my favourite actors. Since I like movies so much there are many actors whose work I like.